Scientist of the Day - Frederick Otis Barton, Jr.

Otis Barton, an American engineer and inventor, was born June 5, 1899. In 1928, the world-famous American naturalist and world traveler, William Beebe, wanted to study the life of the deep sea and was floating about ideas for a diving vessel. Beebe envisioned some sort of small cylinder in which he could be lowered, but Barton heard of Beebe's designs and realized that he, an engineer, could do a lot better. And he did - he designed a submersible sphere that could withstand the pressure of several thousand feet of ocean. Eventually Barton's design came to Beebe's attention, and Beebe realized that Barton's design was indeed better. He also very much liked that fact that Barton was wealthy and could pay for building what they now called the Bathysphere. In return, Beebe would pay the support costs (or rather, he would ensure that the New York Zoological Society paid for them), and Barton would be allowed to accompany Beebe on the descents.

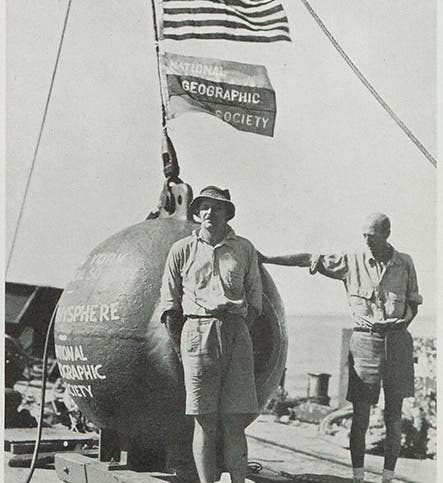

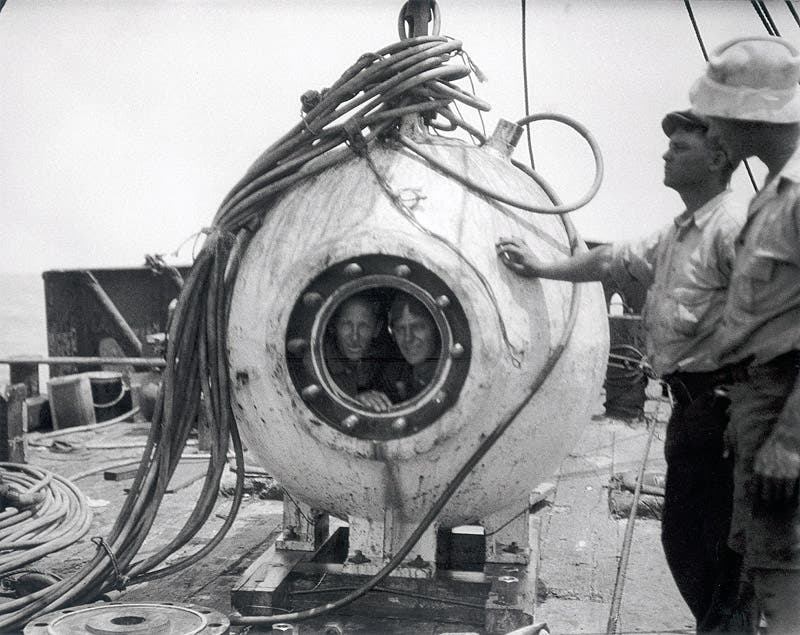

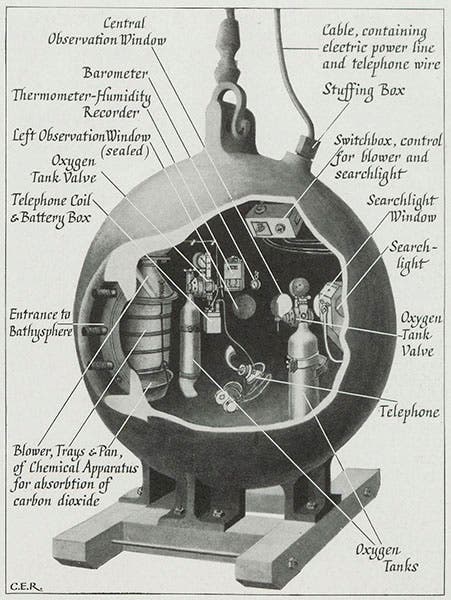

The Bathysphere was very carefully designed and produced – it cost Barton $11,000, which was slightly more than the price of Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis. It was cast of 1"-thick steel, with windows 8" in diameter and 3" thick, made of transparent fused quartz. The sphere was 57" in diameter, which is about the size of a small round dining room table, and it held two occupants, who had to be thin enough to squeeze through a 14" hatch (Beebe did so easily; Barton was a tighter fit). Then the hatch was closed with a 400-pound lid that was firmly bolted in place. It was no place for the claustrophobically inclined. Our first photo shows the two men, Barton in front and Beebe to the right, outside the Bathysphere, and a second shows the two inside and peering out through the quartz window in the hatch, Barton on the right. Since it was impossible to photograph the inside of the submersible, a diagram will have to suffice (third image).

Beebe and Barton made their first descents in 1930 off the coast of Bermuda, first to 800 feet, already a record, and next to 1426 feet. Had Beebe written his famous book that year, he might have called it A Quarter Mile Down. But he didn't. Not much happened in the next three years, due to weather, the economic impact of the Great Depression, and other factors. But in 1934, Beebe and Barton were ready to go again, and on Aug. 15, 1934, they descended in the original Bathysphere to 3,028 feet, a record that endured until 1949. Now Beebe wrote his book, and he called it Half Mile Down (1934). It was a best seller, and although Beebe was already a well-known figure, Half-Mile Down put him in the league of Roy Chapman Andrews and Henry Fairfield Osborn, both of the American Museum of Natural History, as a world-renowned naturalist.

Barton was left behind in the public forum, and he wasn't especially happy about it. But it wasn't really Beebe's fault that journalists loved him and ignored Barton. Barton and Beebe drifted apart, but it was Barton, not Beebe, who continued with deep-sea exploration. After the War, he designed and built a submersible, the Benthoscope, that could withstand even greater pressure, and in 1949, without Beebe, he was lowered to a depth of 4500 feet, which broke the 1934 record, and still stands as the greatest depth attained by a bathysphere suspended from a cable. Barton wrote his own book, The World beneath the Sea (1953), but it did not garner nearly the attention of Beebe’s earlier book. It is an indictment of us all, I suppose, that I have read Half Mile Down but not The World beneath the Sea, although we have both works in our Library.

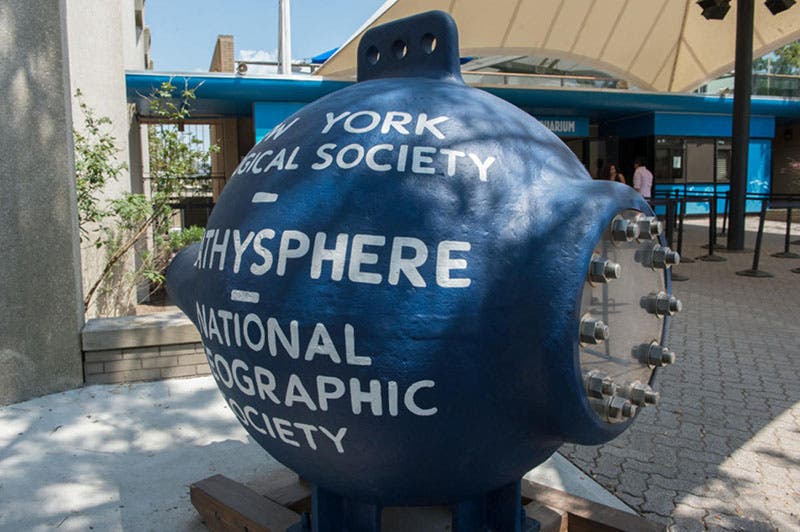

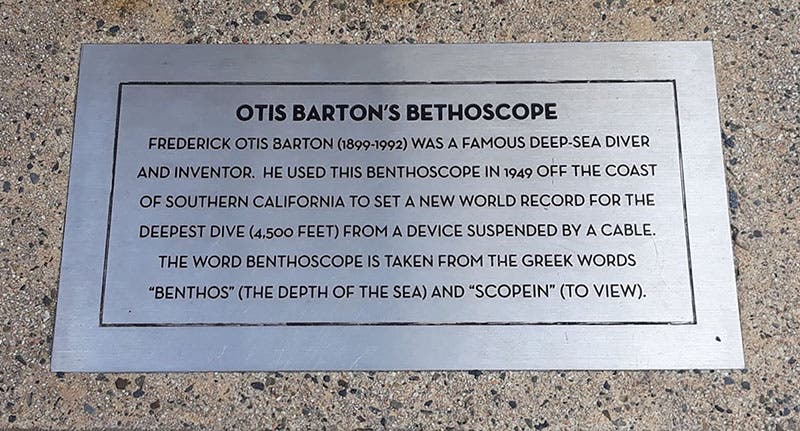

The original Bathysphere, with a new coat of paint, is on display at the New York Aquarium at Coney Island (fourth image); the often-photographed vessel at the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C, is a replica. The very similar-looking Benthoscope, painted white instead of blue, is outside the Los Angeles Maritime Museum (fifth image). It is identified by a plaque (sixth image) that gives to Barton some of the credit that he missed out on during his lifetime.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.