Scientist of the Day - Frederick de Houtman

Frederick de Houtman, a Dutch explorer and astronomer, died Oct. 21, 1627, apparently about 56 years old; his date of birth is unknown. In 1595, the merchants of Amsterdam decided to break Portugal's stranglehold on the spice trade by sponsoring an expedition of four ships to the East Indies. Pieter Keyser, an astronomer/navigator, was giving instructions by Petrus Plancius, a prominent Dutch cartographer, on the need for astronomical observations of the southern stars for the aid of navigators (and globe makers). Houtman accompanied Keyser on the voyage of 1595-97 and apparently absorbed these instructions as well. Both Keyser and Houtman recorded positions of the southern stars, although they did so independently. Keyser died at the end of the voyage, but his observations somehow made it back to Plancius, who included 12 new constellations and their stars on a globe of 1598.

Houtman survived the first voyage, returned home, and then set out again on a second Dutch expedition, 1598-99, and refined his stellar observations. By the time he was done, he had positions for over 300 stars of the southern sky.

To appreciate what Houtman and Keyser were up to, one should realize that at the time, the heavens were divided up into 48 constellations, and it had been that way since Ptolemy of Alexandria published his star catalog in 138 A.D. Ptolemy could see reasonably far south from Alexandria – he could see the Southern Cross, for example – but there was an area of the southern sky that lay below the horizon for Ptolemy, and no European would see those stars until the Portuguese sailed around Africa in the last years of the 15th century. Portuguese navigators must have recorded the new stars, and perhaps they devised constellations for them, but if so, their observations disappeared into the maw that was the Casa da India, the government agency in Lisbon that kept all maps, charts, and navigating instructions in total secrecy. So the star atlases of the late 16th century, right up until 1603, typically have 48 plates, one for each of the 48 Ptolemaic constellations.

The new stars of Keyser and Houtman required new constellations. Twelve were devised: Chamaeleon, Phoenix, Triangulum australe (southern triangle), Apus (bird of paradise), Dorado (swordfish), Musca (fly), Tucana (toucan), Volans (flying fish), Grus (crane), Pavo (peacock), Hydrus (snake), and Indus (Indian).

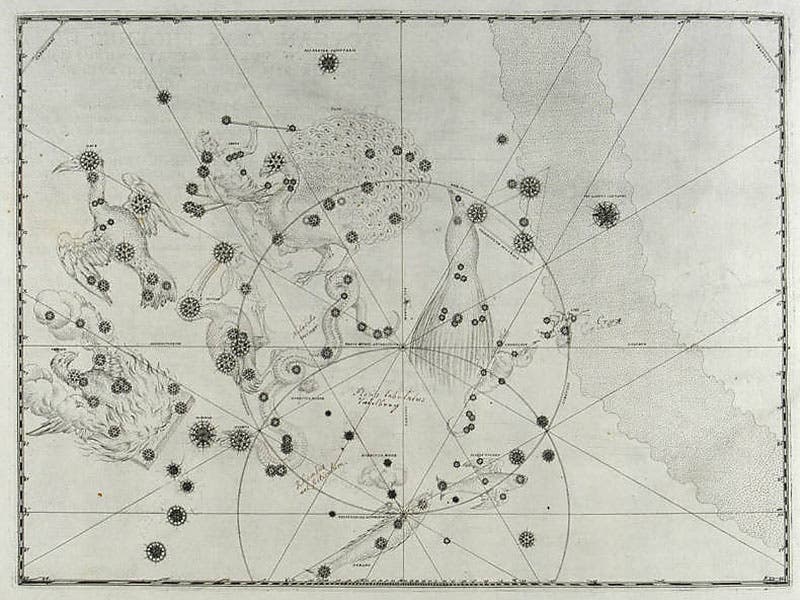

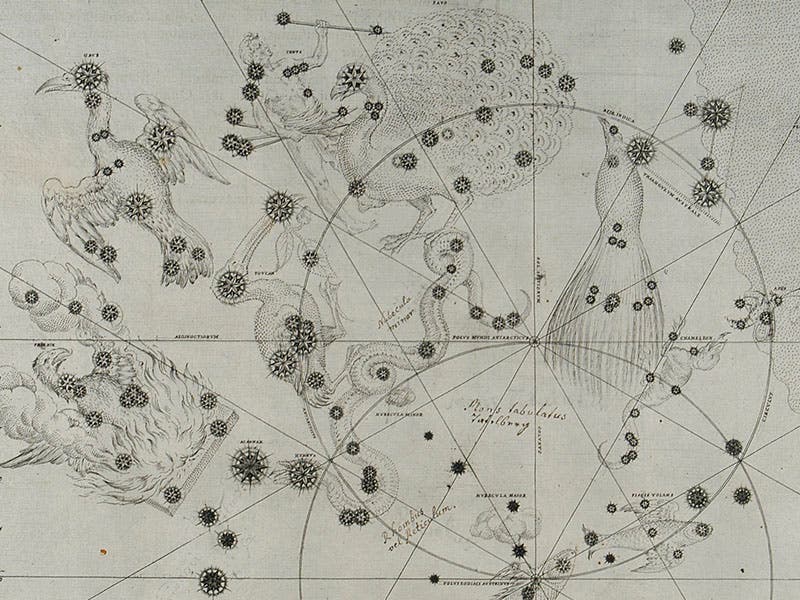

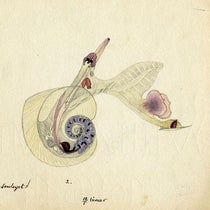

It is not clear exactly who came up with the names. Some think Plancius did, since the 12 new names first appear on his globe of 1598; perhaps Keyser had a hand in creating them as well. What is certain is that Houtman was the first to publish them, along with the positions of the stars that define them. In 1599, at the end of his second voyage, Houtman was arrested in the East Indies and spent two years in prison before he could get home. He whiled the time away compiling a dictionary of the Malay language, and when he finally got back in 1602, he published his Malay dictionary (1603), and at the end he added a catalog in Dutch of the southern stars, listing the longitude and latitude of some 300 new stars and the 12 new constellations that housed 100 of them (most of the other newly observed stars were added to existing Ptolemaic constellations). You can see the first two pages of Houtman’s star catalog here, a link provided by an incredibly useful website on the history of the constellations, Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales. In a remarkably rapid turn of events, the 12 new constellations were pictured on a Willem Blaeu celestial globe of 1603, and on the 49th plate in Johann Bayer's star atlas of 1603, the Uranometria (second image). Bayer’s engraving leaves out all the neighboring constellations, so it is easy to pick out the peacock and the Indian and the combustible phoenix, especially in the detail (third image).

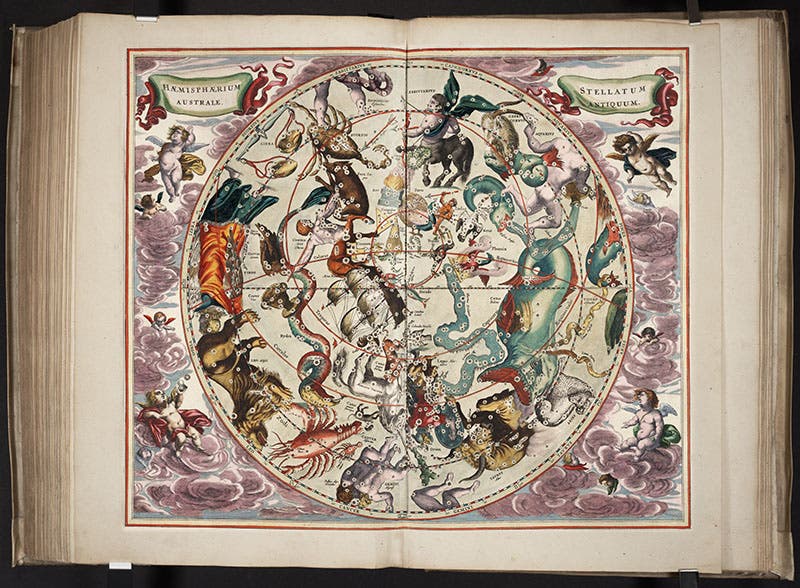

A later hand-colored engraving of the southern skies, from the Harmonia macrocosmica of Andreas Cellarius (1661) shows the 12 new constellations surrounded by the traditional southern constellations known to Ptolemy, such as Argo (ship), Centaurus, and Ara (altar), and even though this map is much busier (and reversed from Bayer’s map), one can still spot the chameleon, the snake, the peacock, the Indian, and the toucan (fourth image). We open this post with a detail of this beautiful star plate, where the new constellations are easier to make out (first image).

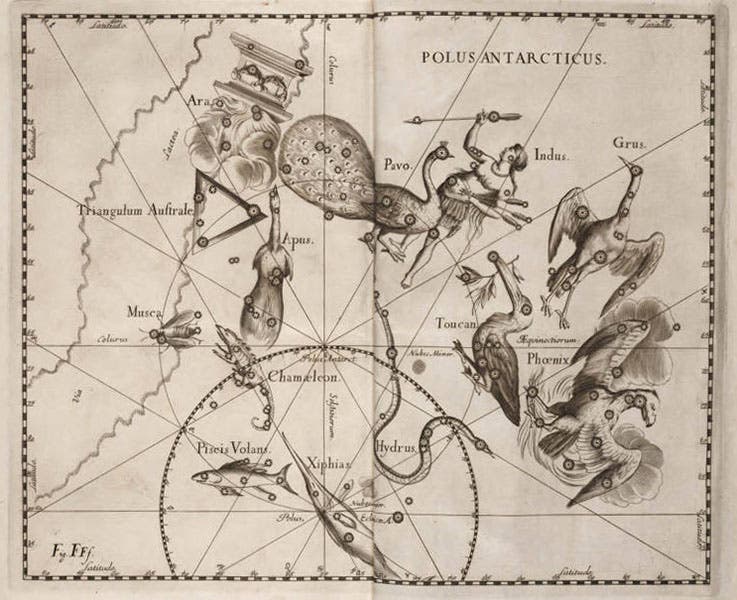

And just for good measure, we include a chart of the southern stars from the Firmamentum sobiescianum, the star atlas of Johannes Hevelius (1690; fifth image). The constellations are the same, but their positions differ slightly, because in the meantime, Edmond Halley had journeyed to St. Helena for better access to the southern sky and had refined the observations made by Houtman and Keyser. The 12 southern constellations of Houtman and Keyser are still in use today, over 400 years after Houtman introduced them.

Houtman apparently became a prominent Dutch citizen in his later years, if his portrait, in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, is any indication (sixth image). With all that regalia, he should be a constellation himself.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.