Scientist of the Day - Francis Bacon

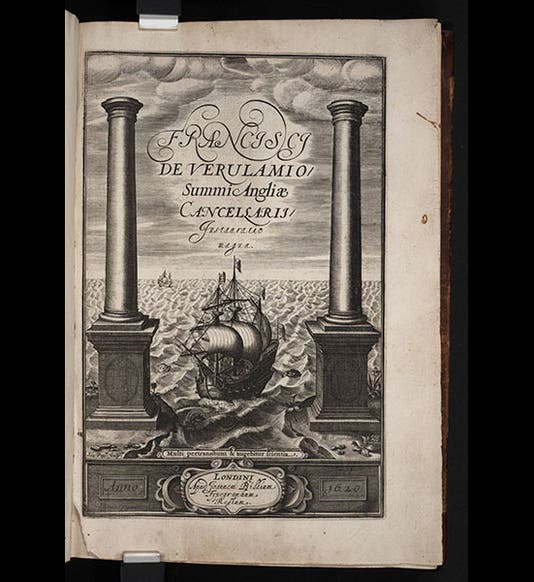

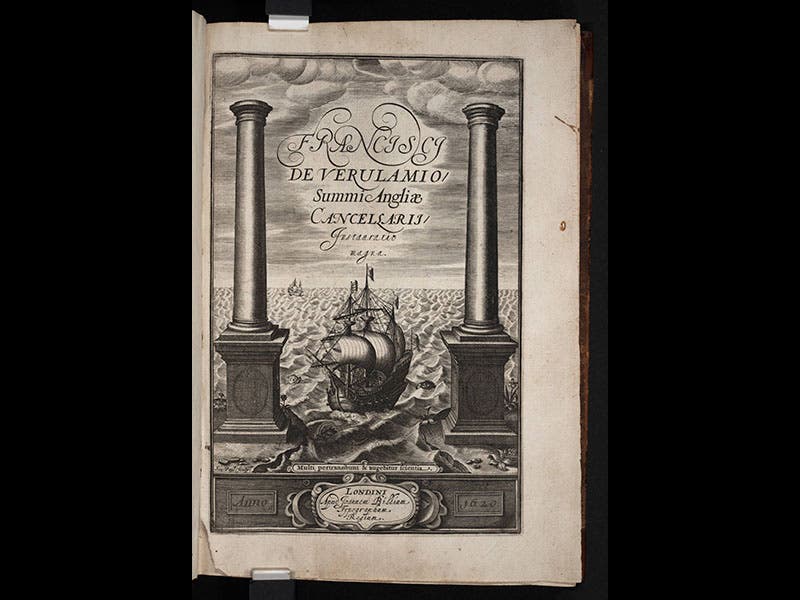

Francis Bacon, the English philosopher and politician, was born Jan. 22, 1561. Bacon, in his Novum Organum of 1620, suggested that there is a new world of knowledge waiting to be discovered, if we abandon the scholastic method of the schools and instead follow a more fruitful "inductive method," based on gathering evidence and devising experiments. Bacon was a wonderful writer, and he liked to capture his major points in witty aphorisms, many of which are quite memorable. Some favorites, all from the Novum Organum, are: 1) "It is hardly possible at once to admire an author and to go beyond him, knowledge being as water, which will not rise above the level from which it fell"; 2) "Philosophy and the intellectual sciences stand like statues, worshipped and celebrated, but not moved or advanced "; and 3) "The human understanding is of its own nature prone to suppose the existence of more order and regularity in the world than it finds". There are dozens more. One of Bacon's favorite visual metaphors was that of the Pillars of Hercules (the Straits of Gibraltar), which the ancients saw as the limit to exploration and discovery. Bacon urged that, like the Renaissance voyagers, we should recognize no limits in our search for truth. He incorporated this idea in several aphorisms, and he used it visually on the engraved title page of his Novum Organum (first image). A version in bronze can be seen on a wall panel on the exterior of the Annex of the Linda Hall Library (second image). The original engraving is in the vault of our History of Science Collection, secure inside our copy of the Novum Organum.

Because Bacon was so famous during his own lifetime (he rose to the position of Lord Chancellor in 1618 and was a peer twice over, as Baron Verulam and Viscount St. Alban, before being disgraced for accepting bribes and forced into retirement in 1621), there is no shortage of biographical material on the major features of his life, but one of the more interesting sources on Baconian biographical byways is the Brief Lives of the antiquarian John Aubrey, compiled in the 20 years before Aubrey's death in 1697. These short essays, hundreds of them, contain snippets of facts and hearsay about his fellow countrymen, most of them derived from interviews with people who knew his subjects. The entry on Bacon is longer than most, and deals with such matters as how Bacon decorated his country house and who treated him shabbily after his fall from grace. But Aubrey personally knew Thomas Hobbes, who in his youth had been a secretary to Bacon, and it was from Hobbes that Aubrey received and passed on the now-famous story of how Bacon died. Hobbes related that, on a coach journey in 1626, it suddenly occurred to Bacon that cold might inhibit the spoilage of meat. So he jumped from the carriage, bought a chicken from a woman in a house nearby, and stuffed it with snow. The chicken was preserved, but Bacon, alas, was not--he immediately fell ill, took refuge in a friend's manor, developed pneumonia, and died. The fact that Bacon, the champion of experimental science, did only one experiment in his life, and it killed him, has always seemed somewhat amusing--in so far as anyone's death can be amusing. It is certainly memorable. And, unlike many such stories, it is probably true.

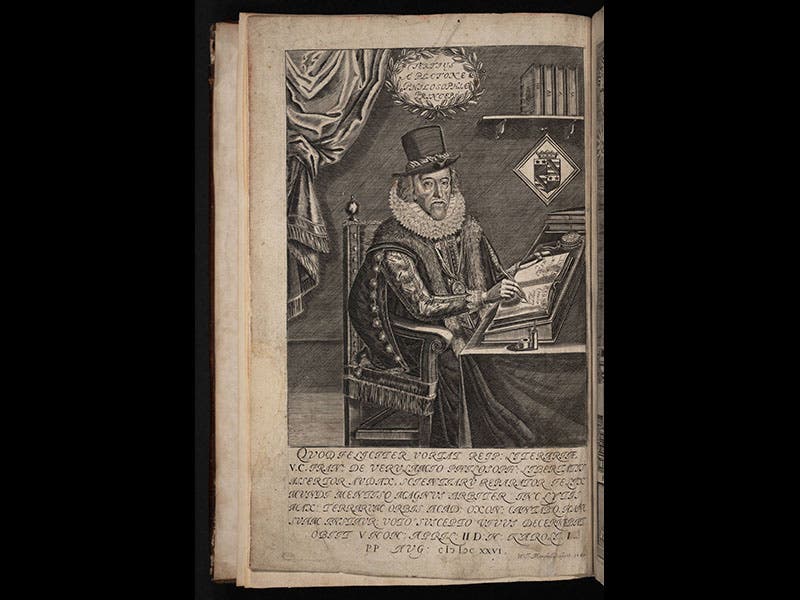

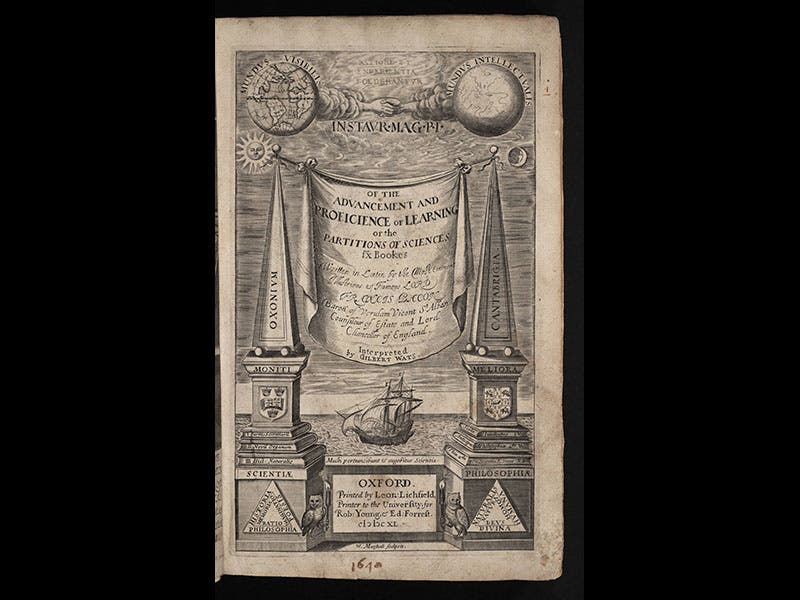

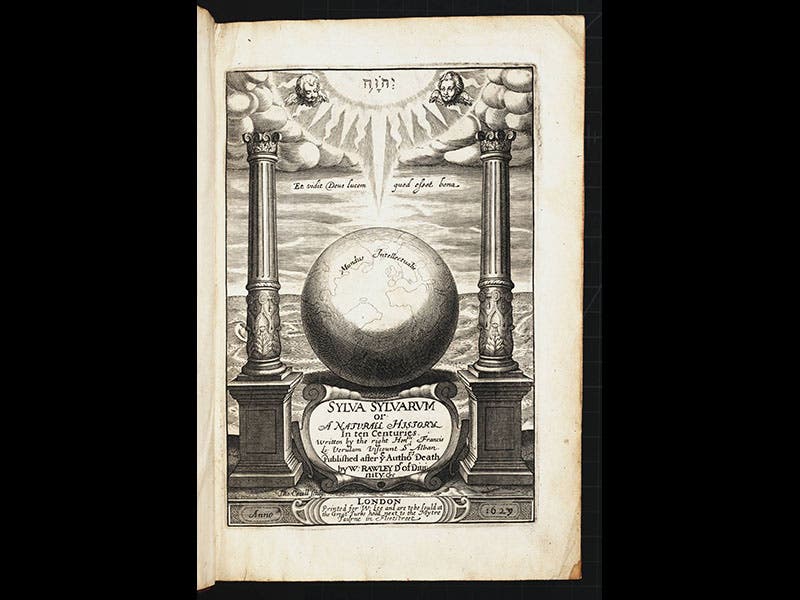

There are a small number of portraits of Bacon in oil, and a large number that are engraved, because nearly all the posthumous collections of Baconian writings--and there have been many--contain an engraved portrait. We display one (third image) that serves as frontispiece to a posthumous (1640) edition of his Advancement of Learning (fourth image). Finally, we show the engraved title page of his Sylva Sylvarum (fifth image; ours is the 1628 edition), where we see another of Bacon’s favorite visual metaphors: the Intellectual Globe, which like the terrestrial globe, needs to be more fully investigated and explored.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.