Scientist of the Day - Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps

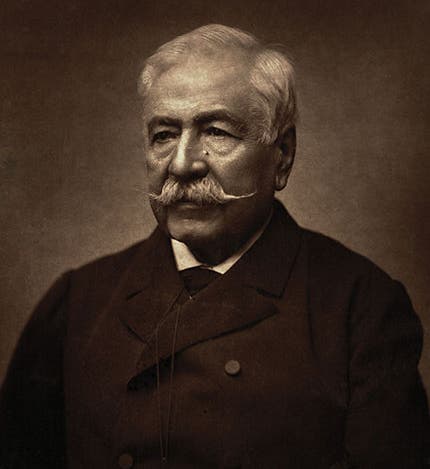

Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps, a French diplomat, was born Nov. 19, 1805. De Lesseps was deeply involved in two French canal efforts. The first was the Suez Canal project. De Lesseps had no training in engineering, but he knew how to make friends with people in power, and how to raise funds. When he was vice-consul to Egypt, he hit it off with the Pasha in Cairo, and he was able to obtain the rights to a canal construction enterprise to connect the Red Sea with the Mediterranean. The French government was very much in favor, because a canal across the isthmus at Suez would cut about 4000 miles off voyages from France to the East Indies. De Lesseps attracted investors, and the project got under way in 1859.

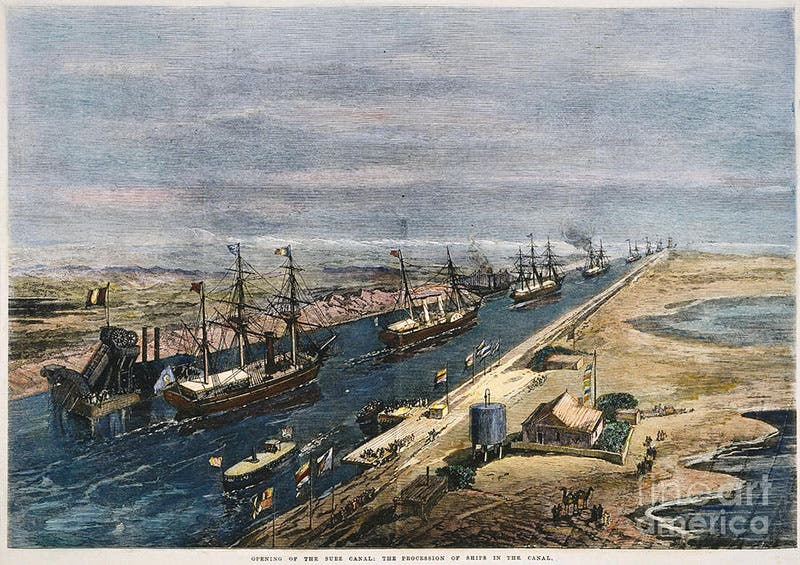

Unfortunately for de Lesseps’ later reputation in Egypt, the Suez Canal was dug almost entirely by conscripted Egyptian laborers, by hand, with the French providing no digging machinery (second image). The workers had to dig a trench 100 feet wide, 50 feet deep, and 100 miles long, for which they received only enough food and water to survive and no pay. Working conditions were horrible, and disease rampant. At least 100,000 Egyptians died over the course of the project.

But the canal was completed, in just ten years. Interestingly, its opening in 1869 (third image) coincided almost exactly with the opening of the trans-continental railroad in the United States, meaning the pace of transportation around the globe picked up significantly in just that one year.

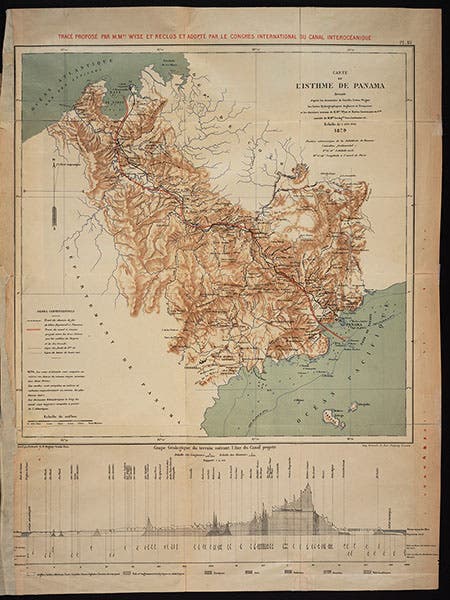

De Lesseps was a national hero for the next twenty years in France. Unfortunately, with one canal under his belt, he decided in 1879 to dig another, across the isthmus of Panama (fourth image). There was great enthusiasm in France for the project, and it easily attracted investors, but the Panamanian terrain and the hostile climate posed insurmountable obstacles for the French, and it didn’t help that de Lesseps insisted on a sea-level canal, with no locks, an impossible stipulation. The effort was abandoned in 1893, with the investors losing nearly everything. De Lesseps, 87 years old, was actually hauled into court and convicted of fraud. He died in 1894, a broken man.

When we celebrated the centennial of the successful U.S. Panama Canal project in our exhibition, The Land Divided, the World United: Building the Panama Canal (2014), we devoted several cases to the failed French project. You may read about the French plan and the French attempt in our online version of that exhibit.

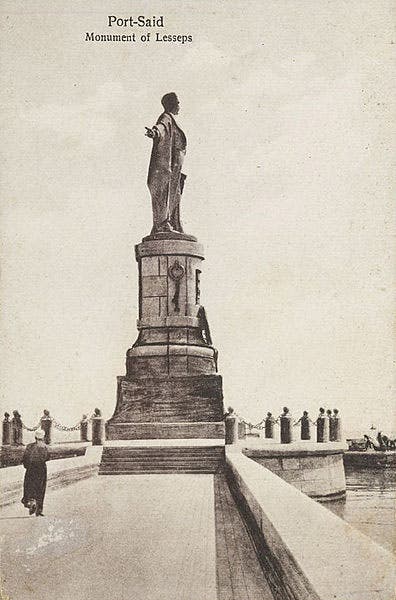

Public irritation with de Lesseps subsided after his death, and it was remembered that while the Panama Canal effort was a disaster, the Suez Canal had been a great success, and it was thought that de Lesseps’ role in that should not be forgotten. So a large statue of de Lesseps was erected in the harbor of Port Said, the northern terminus of the Suez Canal, and unveiled on Nov. 17, 1899 exactly 30 years after the Suez Canal opened for business (fifth image). The statue was the work of Emmanuel Frémiet, a prominent French sculptor.

But even de Lesseps the statue couldn’t stay out of trouble. During the Suez crisis of 1956, the statue was toppled from its pedestal by a hostile mob, and for a while it disappeared from view. The statue eventually surfaced. For some time it lay on the shore in a back harbor at Port Said, but now it has been restored to an upright position in a garden in a nearby shipyard (sixth image). The original pedestal still stands in the harbor, adorned by graffiti, but not by a statue. Will the two ever be reunited? Probably not. The deaths of those 100,000 Egyptian workers during the building of the Suez Canal is still a hot topic in Egypt, and I doubt that de Lesseps will ever again be re-accorded a place of honor on Egyptian soil.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.