Introduction

Women’s Work: Portraits of 12 Scientific Illustrators brings together the work of a group of women who render scientific information into the primary idiom of the human brain, visual imagery. A capable scientific illustrator has the ability to illuminate a subject and stimulate the viewer to look closer, learn more. The illustration will reach vast audiences the way no amount of text or numerical data can. Drawn from the collections of the Linda Hall Library and Missouri Botanical Garden Library, this exhibit highlights six historic women and demonstrates the strong foundation they built by also presenting the work of six contemporary women.

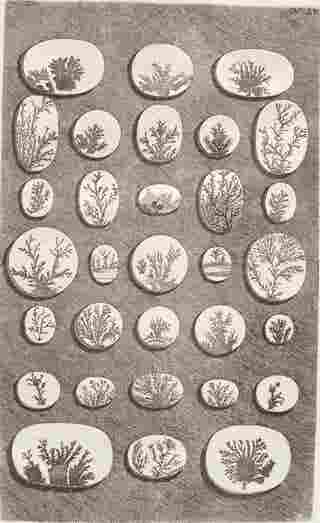

When taking a close look at any part of the history of science, it is nearly impossible to disentangle if rom the larger picture. The women who were (and are) scientific illustrators were influenced by the shape of the society and culture they inhabited. As society became increasingly scientific, women’s contributions became more narrowly defined. By the 17th century, influences from the Renaissance had swept across the Western world. The advent of the printing press accelerated the speed at which information could be exchanged, hastening the dissemination of new discoveries and concepts. Some sought to understand and tame nature by defining it and introducing systems of classification. Others wanted to broaden the narrow scope of their world, voyaging to new “worlds” and returning with plant and animal specimens. Advances in technology improved printing techniques, making opportunities for publication more accessible and affordable.

Women’s contributions to this movement were limited; first by the inhibiting rules of the trade guilds, then by law, and finally and most firmly by social conventions. However, the work of delineator, colorist, or artist was a suitable occupation for a woman. Many of these women remained anonymous, but others were in a position to make a name for themselves and their work continues to be re-discovered and applauded to this day. These women developed a language of visualization that revealed both beauty and precision in execution and opened a window to opportunity for their successors.

Today women are a dominant force in the field of scientific illustration. These illustrators have opportunities never dreamed of by their predecessors. Women in the past were forbidden to enter a surgery; the contemporary illustrator sketches over the shoulders of a surgeon. Women in the past learned what their fathers determined they needed to know; today’s illustrator receives advanced degrees at institutions of higher learning. Some of the contemporary illustrators are scientists with an interest and talent for illustration; others utilize their artistic careers to explore their scientific interests. The women illustrators of the past usually had a male director; today’s illustrators work as part of a team, making use of their own knowledge of specific branches of science.

Women’s Work exhibits landmark illustrations in the history of science by Anna Lister, Maria Merian, Elizabeth Gould, Sarah Drake, Anna Maria Hussey, and Sarah Price. These women led the way at a time when women’s contributions to science were stifled by cultural norms of the day. This exhibit also presents imagery created for the important scientific publications and institutions of our time by Sally Bensusen, Marlene Donnelly, Jessa Huebing-Reitinger, Megan Bluhm, Bee Gunn, and Yevonn Wilson-Ramsey. In full recognition that some very important individuals were left behind, these particular women were3 finally selected because their work demonstrates a range of scientific disciplines, artistic styles, and printing techniques. Their lives demonstrate unique, as well as shared, challenges. Limiting the work of five centuries to selections from twelve women is a difficult task. For that reason we hope this small tribute will be looked on as an invitation to further exploration.