Understanding Eclipses

Wilmari Claasen and Olivia Lanni (University of Zurich)

In the early modern period, eclipses were already well understood. Various documents from the period prove the proficiency of their authors by displaying pages upon pages filled with tables and calculations anticipating where and when eclipses would be visible. Despite the mathematical elegance and reliability of these predictions, the occurrence of an eclipse still carried a lot of negative cultural significance.

What is an Eclipse?

An eclipse takes place when a planet or natural satellite temporarily blocks sunlight from reaching another celestial body. A lunar eclipse occurs when the Earth’s shadow falls onto the Moon, and a solar eclipse occurs when the Moon’s shadow falls onto the Earth. Both instances create a fascinating interplay of light and shadow based on the alignment of the celestial bodies.

The Dragon’s Head and Tail

In his book, Sacrobosco uses the allegory of the dragon’s head and tail to refer to two points in the sky, specifically those that mark where the Moon’s orbital path intersects with the ecliptic of the Sun. The ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. Applied to the image of the dragon, the Dragon Head (Ascending Lunar Node) is the northern touchpoint and the Dragon Tail (Descending Lunar Node) is the southern one. The Head is the symbol bent upwards, the Tail bent downwards.

As the Moon crosses into the path of the Earth through the first node, it eventually moves “behind” the Earth, allowing for a lunar eclipse, before leaving the Earth’s path again through the other node. The same occurs during a solar eclipse when the Moon moves in front of the Sun. Eclipses were explained using this imagery; the disappearance of either the Sun or the Moon was depicted as the equivalent of a dragon swallowing and releasing them again.

Lunar and Solar Eclipses

The following translations demonstrate how Sacrobosco’s use of dragon terminology made eclipses understandable to his readers:

Lunar and Solar Eclipses

Notandum etiam, quod quando est eclipsis lunae, est eclipsis in omni terra, sed quando est eclipsis solis, nequaquam, imo in uno climate est eclipsis, et in alio non, quod contingit propter diversitatem aspectus in diversis climatibus.

It should also be noted that when a lunar eclipse occurs, there is an eclipse (visible) to the entire world, but if it is a solar eclipse, then absolutely not, quite the opposite, (rather,) there is an eclipse in one area (climate), but not in another, which occurs because different areas results in different perspectives.

Unde cum in plenilunio Luna fuerit in capite uel in cauda draconis sub Nadir Solis, tunc terra interponetur Soli et Lunae. Unde cum Luna lumen non habeat nisi a sole, in rei veritate deficit à lumine.

When now the Moon in Full Moon moves into the head or the tail of the dragon at the Nadir (lowest point) of the Sun, then the Earth interposes (itself) between the Sun and the Moon. Now, since Moon does not have (moon)light without the sun, it is now truly deprived of (all) light.

Cum autem Luna fuerit in capite uel in cauda draconis, […], tunc corpus lunare interponitur inter aspectum nostrum et corpus solare. Unde obumbrabit nobis claritatem Solis, et ita Sol patietur eclipsums, non quia deficiat lumine, sed deficit nobis proper interpositionem Lunae inter aspectum nostrum et solare corpus.

But when now the Moon moves into the head or the tail of the dragon, […], then the Moon’s body interposes (itself) between the view of our body and that of the Sun. When (the Moon) now overshadows the brightness of the Sun, then the Sun will suffer an eclipse, it is however not deprived of light, but (instead) the sudden interposition of the Moon makes us deprived (of light) because of its position between our view and the body of the Sun.

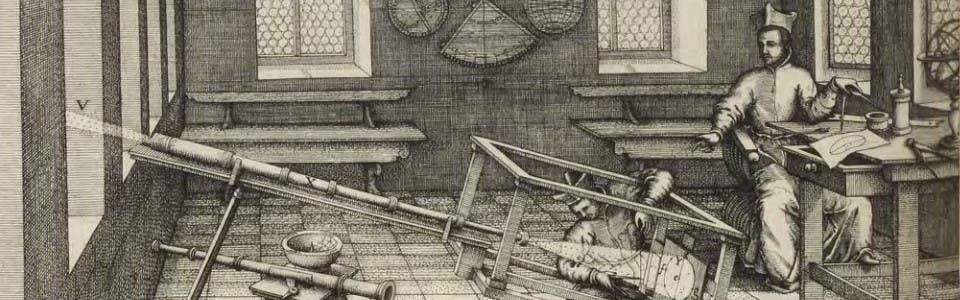

De Sphaera’s Volvelle

Sacrobosco’s work also includes a volvelle, or wheel chart. A volvelle consists of one or several movable paper circles and pointers rotating on a central pivot. They are used to establish astronomical positions or tides and are directly attached to the page in the book. The reader could manipulate them accordingly. They are pedagogical tools and were especially popular in and astronomical books.

The volvelle shown in this image enables the user to manually recreate lunar eclipses by rotating the individual pieces.