Cultural Anxieties Surrounding Comets and New Stars

Wilmari Claasen and Olivia Lanni (University of Zurich)

Early modern society lacked the separation of science and religion that we have become used to today in some parts of the world. We see this clearly in the sighting of comets and new stars.

Astrophysical Properties of Comets

Astronomers cataloged the astrophysical properties of comets, noting their altitude, speed, size, and orbit trajectories (the latter of which could be calculated using the Sun). They speculated on the effects a passing comet might have on the Earth. Observations about the length of a comet’s tail in relation to its speed across the sky thus led some astronomers to see comets as evidence for the Earth’s motion.

The function of comets was subject to lively debate, with theories ranging from comets being a source of heat for faraway planets to comets having been involved in the formation of the Earth.

Comets, Religion, and the Apocalypse

In the seventeenth century, comets were a source of fear and uncertainty for many. In An Astronomical Description of the Late Comet (1619), English astronomer John Bainbridge sought to assuage a popularly held fear that the tail of a comet could set the Earth on fire. He assured his readers that the rays of a comet’s tail were not concentrated enough to affect the Earth. Instead, Bainbridge connected comets to the divine. He was convinced that comets were direct messengers and omens of God and wrote that people need not be afraid of the comet itself, but rather “the great and potent Creator thereof”; in other words, comets were to be seen as a call to repent from sin. He also touched upon the “new star” that led the Wise Men to Christ, again linking rare astronomical phenomena with religious events.

Astronomers would make prognostications about the future based on descriptions of previous comet appearances, which they linked to major historical events. Bainbridge cited the appearance of five comets within ten years around the time of Martin Luther’s preaching and concluded that a recent bright comet (which appeared at the end of 1618 and could be seen all over the world) portended another wave of Protestantism. Separating himself from serious prognostications for a moment, Bainbridge humorously concluded his Astronomical Description by expressing hope that the comet would bring ”happie tidings of some munificent and liberall Patron’ to his studies.”

A link between comets and the apocalypse characterises the work of Scottish astronomer, George Smith. Smith’s A Treatise of Comets (1744) was inspired by sightings of the so-called “Great Comet” of 1744, which was visible in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres and was later described as the most beautiful comet of the eighteenth century. Based on his measurements, Smith concluded that this comet was as big as the Moon and would have affected the tides had it passed close enough to the Earth. According to Smith, this would have been enough to cover the mountains and the entire earth; a “second general Deluge,” or flood of biblical proportions. Smith was further persuaded that the Earth would have been completely destroyed had there been a collision. He even speculated that the eventual end of the world might be caused by such a comet, an opinion he claimed to share with the English theologian and natural philosopher, William Whiston.

According to Smith, Whiston argued that comets would be used as “Punishments of the Impenitents after Death.” Smith disagreed with this on grounds that “[a] few Comets wou’d have been sufficient for a Hell to the whole Planetary System”; that is, there were too many comets in existence for their function to be the punishment of sins. Smith did, however, see comets as the cause behind certain biblical events. As well as ascribing floods to comets, he speculated that comets might cause a much more dramatic solar eclipse than any other circumstance and cited this as the cause of the plague of darkness in the Old Testament.

Earthquakes were another natural disaster thought to be related to comet sightings. Around 1713, the German astronomer, Maria Margaretha Kirch, warned against the dangers of comets in Vorbereitung, zur grossen Opposition (Preparation for the Great Opposition) by connecting past observations of comets with earthquakes that happened shortly after. She also endeavored to prove that some alignments of Jupiter and Saturn could forecast comets, citing historical precedent.

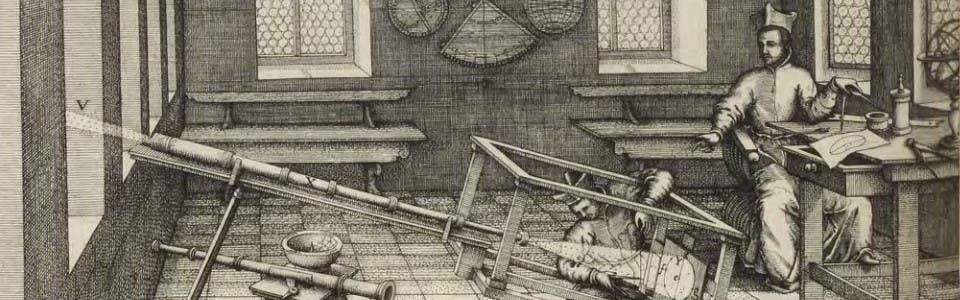

Tycho Brahe and the New Star

As with comets, early modern views on the so-called “new stars” consisted of a mixture of astronomy, astrology, and religion. Danish astronomer, Tycho Brahe, sought to combine an astrophysical description of a new star that appeared in 1572 (known today to have been a supernova) with attempts to interpret it as an omen. In his De nova stella, later translated into English as Learned: Tico Brahæ, his astronomicall coniectur of the new and much admired [star] which appered in the year 1572 (1632), Brahe aimed “to lay a ground-worke, not onely to the Explanation of this Starre, but also to the whole Science of Astronomy.” He provided an elementary distinction between comets and new stars: New stars do not have tails, and comets usually have them, though not always. Brahe also insisted that this was indeed a new star, and not merely a celestial object that “received an accidentall light from some of the old Starres,” as others had conjectured.

Brahe soon moved on to prognoses of the future based on the appearance of this new star. Like most astronomers of his time, he was convinced that rare astronomical phenomena held “power of Divination,” though he allowed the caveat that it was extremely difficult to arrive at correct interpretations due to a lack of complete knowledge of the cosmos. Nevertheless, he wrote a detailed interpretation of the star. Based on observations like the brightness of its light, its color, its relation to the constellations of the zodiac, and its appearance during the seventh so-called “revolution of the planets,” Brahe predicted a time of prosperity, peace, and religious unity intermingled with violence and trouble. He related this to the biblically foretold golden age of peace before the end of the world, as well as a recently discovered sibylline prophecy that likewise predicted an era of peace before the destruction of the universe.

The intermingling of astronomy and biblical apocalypse in Brahe’s text evokes the complexity of so much early modern writing about the Sun.