Navigating by the Sun

Wilmari Claasen (University of Zurich)

Maritime technologies

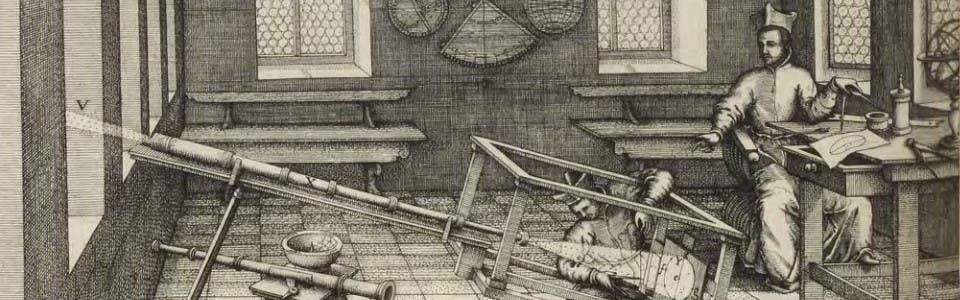

Along with fixed stars and the Moon, the Sun was central to navigation by sea in early modernity. Navigational instruments determined the position of the Sun in relation to the horizon or other stars. Astrolabes were complicated devices, simplified versions of which were used to measure the height of the Sun at noon. The cross-staff—a wooden rod with a sliding cross-piece—showed the angle between a star (such as the Sun) and the horizon. A quadrant or a sextant—which involved two mirrors and was used in conjunction with a telescope—could be used to measure the altitude of celestial objects.

Sailors compared measurements taken with these instruments with other data to calculate the latitude of their position (that is, how far to the north or south they were of the equator). Nautical almanacs—periodical publications containing astronomical information specifically intended for navigators— printed tables of solar declination, useful to find the distance of the Sun north or south of the equator. Knowing the declination of the Sun at noon on any given day was a vital figure in latitude calculations.

Although the astrolabe has a much older history, European sailors started using it and the cross-staff more widely during the fifteenth century. A sailor could use a cross-staff, a more recent invention, by holding one end of the staff underneath the eye and aligning its cross-piece with the Sun and the horizon, which would then indicate the angle between the two. Such instruments greatly simplified the calculations required to determine latitude.

The quadrant was another mathematical instrument commonly used to measure angles, including the altitude of celestial objects. Navigation using a quadrant required knowledge of the Sun’s declination on any given day, which could be found in a nautical almanac. The sextant emerged later in the period and, in addition to latitude, could calculate the more elusive longitude (the distance to the east and west of the prime meridian) by observing the angle between the Moon and fixed stars.