Tranquil Corythosaurus, 1957

During the post-war years, the figures from the Zallinger mural greatly influenced public perceptions of dinosaurs in the United States. In central Europe, the foremost painter of dinosaur restorations was Zdenek Burian. His canvases were used to illustrate a number of popular books on prehistoric life by Joseph Augusta, and in the the late 1950s and 1960s these were translated into English and widely circulated. So the Burian illustrations offered an alternative to those of Zallinger, or of the late Charles Knight. But there was not much of a difference. Apatosaurus and Diplodocus stand quietly by their respective swamps, accompanied by partially submerged relatives. A Tyrannosaurus besets a pair of Trachodon, but none of the three lifts a leg off the ground, or even seems to be moving at all.

The restoration of Corythosaurus, painted in 1955 (see below), shows one specimen standing semi-upright, with its tail on the ground, while another contemplates its reflection in the water. The pose of the foreground figure had been the standard ornithopod stance since Dollo's restoration of Iguanodon, and it would continue to be so until the 1970s.

One of Burian's other paintings shows a Brachiosaurus submerged up to its eyeballs in water. The notion of snorkeling sauropods is an interesting sidebar in the history of dinosaur restoration.

Snorkelling Brachiosaurus, 1957

Zdenek Burian in 1941 painted a pair of Brachiosaurus that were completely immersed in water (see below). This notion of Brachiosaurus as a bottom-walking surface-breather has an interesting history. Apparently the idea was first proposed by Edward Cope around 1897, and Charles Knight did a drawing at that time of such a snorkeling sauropod. The drawing was apparently published in 1897 in the Century Magazine, a journal that our Library does not hold, but twenty years later Henry F. Osborn and Charles Mook reproduced the drawing in their monograph on Camarasaurus. The Knight drawing, in its 1921 manifestation, can be seen on the right.

When Burian made his painting, the idea of an under-water sauropod was still scientifically respectable. However, in 1951, K. A. Kermack, in a brief article, pointed out that it was physically impossible for any creature to breathe at the surface with its lungs submerged more than a few feet, because of hydrostatic pressure. Certainly Brachiosaurus, with its lungs twenty feet down, would have been utterly unable to bring air into its lungs. Nor would its cardio-vascular system have had any chance of working. The notion of a snorkeling sauropod was killed on the spot. Or should have been.

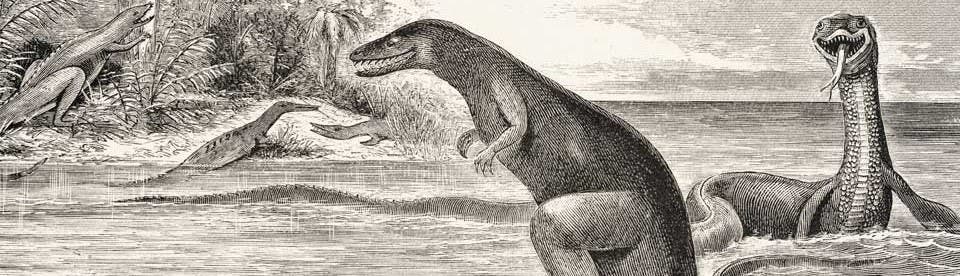

A T. rex and Trachodon Tableau, 1957

The image below is another painting by Zdenek Burian that was included in Joseph Augusta's book, Prehistoric Animals. This painting, executed in 1938, shows two Trachodon being attacked, or at least threatened, by a Tyrannosaurus. There is a wonderful tension in the posing of the animals, as the hadrosaurs lean away from the predator. But it is still a very passive tableau, with none of the animals actually moving.