Apatosaurus Gets a Head, 1936

The great Carnegie Museum specimen of Apatosaurus louisae was discovered by Earl Douglas in 1909 and mounted by 1913. William Holland spent the next twenty years preparing drawings and working on a memoir, but he died in 1935 without having published it. The material was turned over to Charles Gilmore, who produced the desired monograph in short order.

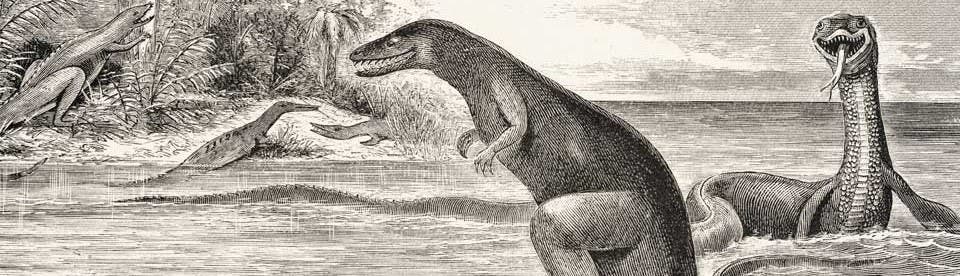

The illustration reproduced at right is a little known but quite charming charcoal drawing by A. Avinoff, who was the new Director of the Museum, and obviously quite an accomplished artist. The casual viewer will not be surprised to note that Apatosaurus is shown with a head, but in fact the skeleton had stood in the Museum for twenty years without a head, because Holland was unsure as to what head it should wear. No skull had ever been found directly associated with an Apatosaurus skeleton. Marsh had drawn a Camarasaurus-like skull on his restoration (then called Brontosaurus, see item 18), and the American Museum had followed Marsh's lead and had mounted a similar short, wide skull on their restored skeleton.

A Camarasaurus-like skull was found in the Carnegie quarry, but Holland had his doubts that it belonged to the specimen, and he leaned toward a long, narrow Diplodocus-like skull that had been found in the same quarry. But he never had the nerve, or the backing, to mount it. After his death, tradition prevailed, and a cast of the Camarasaurus-like skull was mounted on the skeleton, although Gilmore too was unsure that it belonged.

Holland's reservations about the skull turned out to be well founded. In the 1970s it was conclusively demonstrated that all Apatosaurus mounts were wearing a Camarasaurus skull, and in the early 1980s, in a wave of skeletal revisionism, camarasaurid heads everywhere were removed and exchanged for the proper diplodocid model.

It is interesting to note that Avinoff, in his restoration, seems to have borrowed the facial expression of his Apatosaurus from Christman's sketches of 1921 (see item 39), which now seems utterly appropriate, since Christman was sketching a Camarasaurus, and the Carnegie specimen is here wearing a Camarasaurus head.

For a photograph of the Carnegie Apatosaurus mount, with a detail of the disputed head, see the image below.

The Carnegie Apatosaurus Mount, 1936

The photograph of the mount in the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh shows Apatosaurus lousiae (Apatosaurus is on the right, the famous Carnegie Diplodocus is at the left). If you look closely, or better yet, if you look at the enlarged detail on the right, you will see that Apatosaurus has two heads, one mounted on the neck, and one in a case below. The one on the skeleton is in fact a cast of the one in the case, and it is a cast because Charles Gilmore was not at all sure that it belonged on the skeleton. The man who supervised the reconstruction, William J. Holland, was not sure either. In fact, Holland leaned toward a Diplodocus-like skull that had been found in the Carnegie quarry, rather than the Camarasaurus-like skull that the American Museum in New York, and the Peabody Museum in New Haven, had installed on their skeletons. Holland had written a paper in 1915 in which he gave good reasons why the Diplodocus-like skull should be preferred. But he never mounted that skull on the skeleton; he either lacked the courage of his convictions, or he was not allowed to install the skull of his choice. So the Carnegie Apatosaurus stood for twenty years without a skull, until finally a cast of the conventional Camarasaurus-like skull was put in place.

As it turns out, of course, Holland was right, and the wrong skull had been installed. The situation was not corrected until the 1980s.