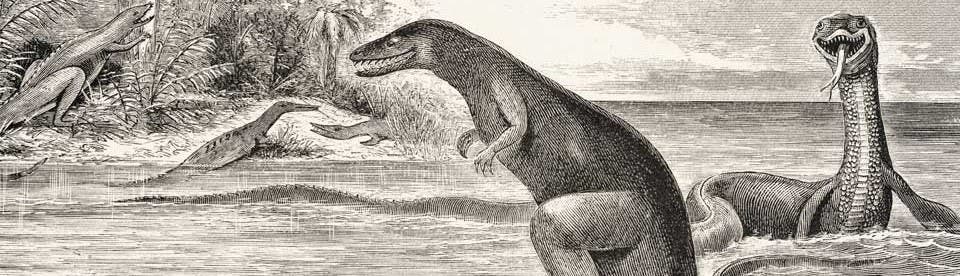

An Agile Ornitholestes, 1914

Charles R. Knight was the first great illustrator of dinosaurs, and perhaps still the champion of the art. We have already seen his 1898 model of a pair of Dryptosaurus, his 1901 sculpture of Triceratops, and his 1907 painting of the browsing Diplodocus. By 1914 his fame was such that the American Museum Journal devoted an entire article to his craft.

We are used to seeing color reproductions of his paintings today, but in the early decades of the century it was only the visitor to the American Museum or the United States National Museum who could see the original color canvases. Reproductions were scarce, and then always in black and white.

One of Knight's finest drawings is shown on the right: Ornitholestes catching Archaeopteryx. Since it was executed in charcoal, nothing is lost but size in the black-and-white reproduction. Ornitholestes had been described and named by Henry Osborn in 1903.

The specimen was nearly complete, so Osborn was able to include a skeletal restoration in his original paper. However, Osborn's restoration, while bipedal, did not show much sign of vim and vigor. Knight has restored not only flesh to the bones, but life, and indeed the joy of life, to the animal.

Knight painted much more than dinosaurs, and this article is largely concerned with his mammal restorations. But two other Knight dinosaurs are reproduced: his painting of Allosaurus feeding on the remains of a sauropod, and a charcoal sketch of Diplodocus (below).

Osborn's Ornitholestes, 1903

This new dinosaur was discovered by the American Museum Expedition of 1900, at Bone Cabin Quarry in Wyoming. Because it seemed to be very light and agile, with great grasping power, Osborn guessed that it might have pursued Jurassic birds, and so he named it Ornitholestes, the “bird robber.” The specific name honored the head preparator at the Museum, Adam Hermann.

Allosaurus in Bone and Flesh, 1907 and 1914

In 1907, the American Museum of Natural History in New York unveiled a novel dinosaur display; they mounted a full skeleton of an Allosaurus over the skeleton of the tail of a sauropod, as if the Allosaurus were feeding on the sauropod remains. Scientific American put a photograph of the mount on the cover of this issue, along with a watercolor restoration by Charles Knight (right)

Knight’s restoration is not very well known, because several years later he replaced it with a painting (left) that more closely mirrored the position of the Allosaurus as mounted. That second painting is reproduced in Dickerson’s 1914 article.