Dinosaurs in Motion

Swimming Corythosaurus, 1916

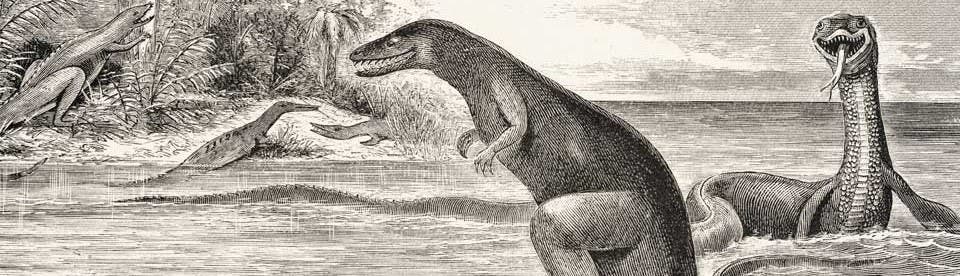

Until 1910 or so, most hadrosaur specimens looked more or less alike, with similar flat, duck-bill-shaped heads, which was why paleontologists had trouble trying to decide whether they were dealing with one genus or several, and why there was such a confusion of names. Then, rather suddenly, a great variety of hadrosaurs, with unmistakably different head crests, began to be recovered from the Red Deer River in Alberta. Foremost in the hunt was Barnum Brown, who discovered Kritosaurus, Saurolophus, and Prosaurolophus in short order. But the prize specimen found by Brown was a skeleton of what he called Corythosaurus, after the helmet-shaped crest on the skull. The first specimen was found in 1912 and proved to be virtually complete and articulated, with even some skin impressions on one side. Although Brown published his find initially in 1914, we exhibit his second paper, because it includes a life restoration of Corythosaurus in its natural habitat (see illustration at right).

Brown thought Corythosaurus was a swimmer, for interesting reasons. He said that if you place the type specimen in a horizontal position, it looks like it is swimming (see second illustration below). And indeed, the swimming figure in the restoration has exactly the same pose as the fossil. It is doubtful that Brown really thought that a Corythosaurus, having swum through life, would maintain this same posture as it died and awaited fossilization. Nevertheless, he looked at the fossil and saw a swimmer. The concept so delighted Charles H. Sternberg that he used this very drawing as the frontispiece for his book, Hunting Dinosaurs, that was published the next year (see item 28).