Scientist of the Day - Edwin Land

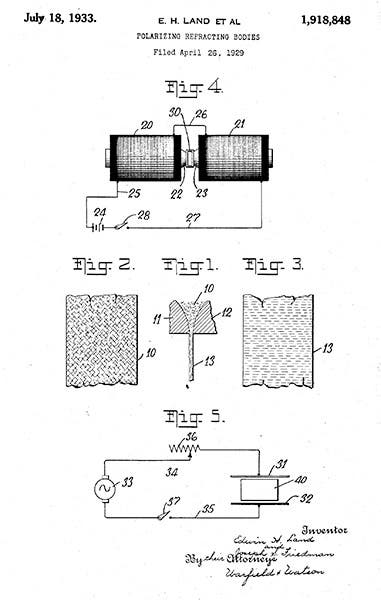

Edwin Land, an American scientist and inventor, was born on May 7, 1909 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. As a child, Land became fascinated with optics after reading a textbook on the subject by Johns Hopkins University physicist, Robert W. Wood. Land was particularly intrigued by Wood’s discussion of polarization, the tendency of certain substances to block the passage of light waves unless they are oscillating in a specific direction. Until the 20th century, researchers eager to explore this phenomenon had relied on natural polarizers like calcite. Land wondered if it might be possible to create synthetic polarizers, whose ability to reduce glare could have a variety of useful applications. Fueled by these speculations, Land enrolled at Harvard but eventually withdrew to pursue his polarizer research independently in New York City. Working in secret at a Columbia University laboratory, Land first attempted to synthesize large polarizing crystals. When that proved ineffective, he mixed a large number of microscopic crystals into a liquid. Applying a strong magnetic field to this suspension caused the crystals to align themselves in a single direction. He then dipped a piece of celluloid into the mixture, and as the lacquer dried, the crystals retained their new orientation. The resulting plastic sheet was the first artificial polarizer. Land submitted a patent for his new invention, the first of over 500 he would secure throughout his career (second image). In 1932, he teamed up with a Harvard professor named George W. Wheelwright, III to transform his polarizers into commercial products. Five years later, their Cambridge-based company, Land-Wheelwright Laboratories, adopted a new name: Polaroid.

Edwin Land’s first patent for an artificial polarizer (Google Patents)

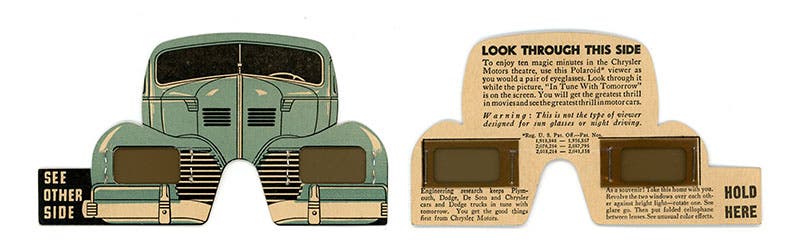

Early on, Land hoped to incorporate his polarizers into car windshields and headlights to prevent drivers from being blinded by oncoming nighttime traffic. When automakers proved resistant to the idea, Polaroid explored other possibilities, including photographic filters, sunglasses, and 3-D movies. The last of these made a prominent appearance at the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair. Visitors to the Chrysler Motors pavilion could don a pair of polarized glasses to watch a 3-D film of the company’s assembly lines (third image).

Polaroid viewer from the Chrysler Motors pavilion at the New York World’s Fair (MIT Museum)

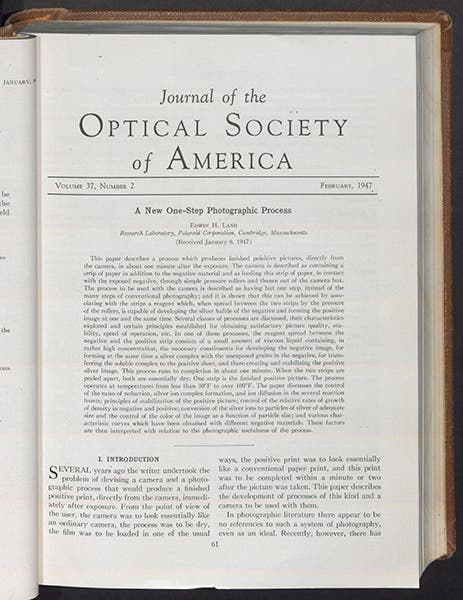

Following the outbreak of World War II, Land was recruited as a consultant for the National Defense Research Committee. As Polaroid started producing millions of bomb sights and goggles for the military, his attention turned to another project. During a 1943 vacation in Santa Fe, Land’s daughter, Jennifer, asked an innocuous question: Why did she have to wait to see the snapshots her father was taking during the trip? In the 1940s, developing photographs was a time-consuming process that required special equipment and expertise. Land now considered whether he could reproduce the chemistry that took place in a darkroom within the confines of a handheld camera. What was necessary, Land concluded, was a new camera whose film contained a sealed reservoir filled with chemicals. After taking a picture, the exposed film would slide through a pair of rollers, which popped the reservoir and triggered both the development of the film negative and the production of a positive image. The idea was straightforward enough in principle, but it took Land and researchers at Polaroid four years to develop a functional prototype that could create a photograph in just one minute. He unveiled their handiwork by snapping a self-portrait at a February 1947 meeting of the Optical Society of America (fourth image). From that moment forward, Polaroid became synonymous with instant photography.

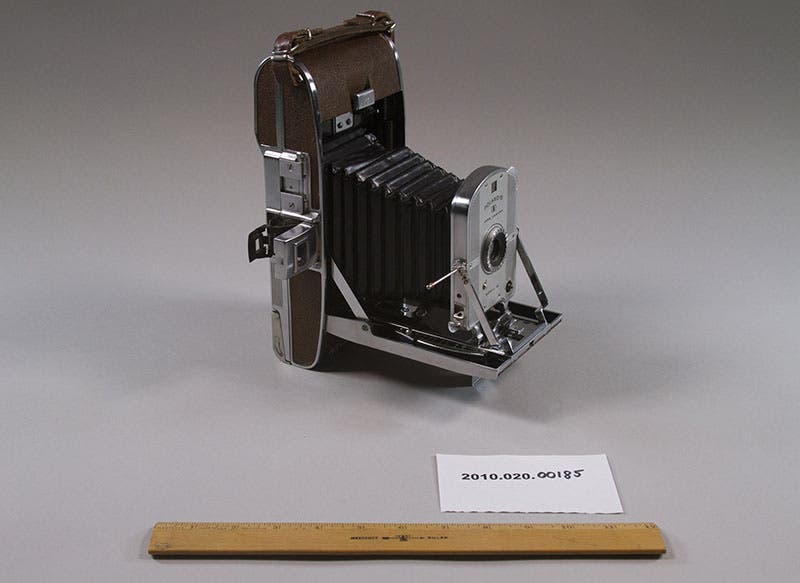

The first Polaroid camera, the Model 95, went on sale the following year (fifth image). Despite producing only sepia-toned images, consumers snatched it off the shelves. Full-fledged black-and-white images would have to wait until the 1950 release of a new form of film developed by Polaroid chemist Meroë Morse. Unfortunately, Land soon discovered that photographs taken with Morse’s film faded over time. Polaroid eventually resolved the issue by providing a stabilizing liquid that users could swab on the surface of their photos. Left on its own, this coating could take fifteen minutes to dry, which led many people to shake their photos to speed up the process. (Contrary to popular wisdom, shaking a Polaroid photograph does nothing to accelerate the speed at which an image appears.)

Polaroid Model 95 Camera, which went on sale in 1948 (MIT Museum)

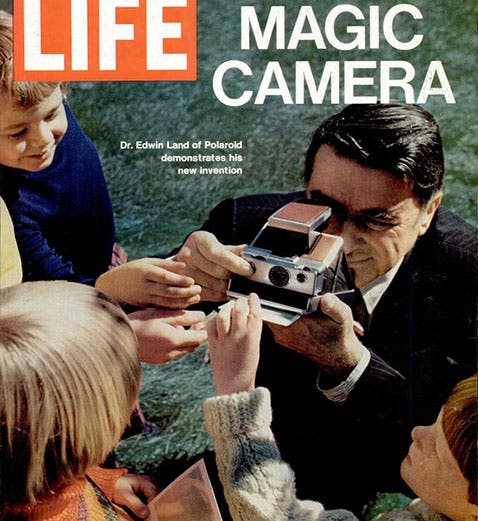

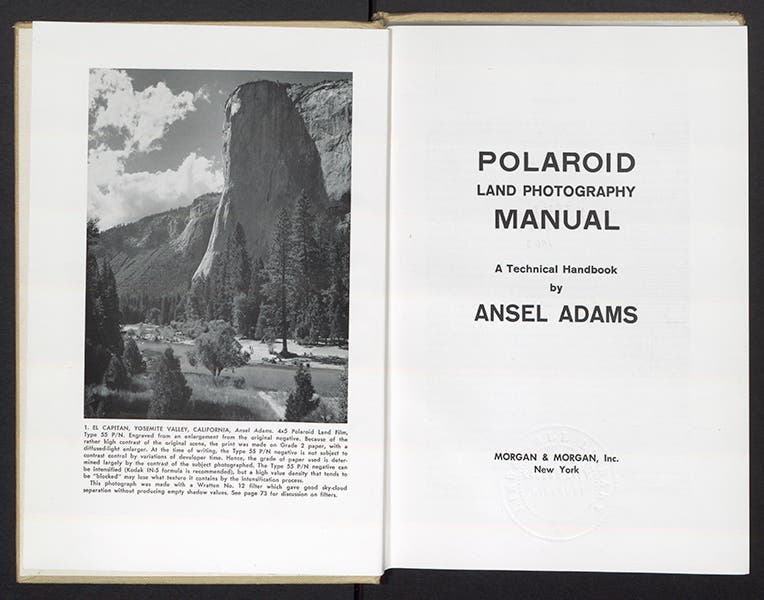

Despite these complications, Polaroid soon cultivated a loyal fanbase, including amateur photographers and professional artists like Ansel Adams. Adams was an early supporter of Polaroid’s new cameras, and Land eventually persuaded him to become a consultant for the company (sixth image). Soon other artists, including Dorothea Lange and Andy Warhol, embraced Polaroid photography, particularly following the company’s introduction of color film in 1963. Land continued to develop improved cameras, culminating in the 1972 release of the SX-70 (first image), a compact camera that embodied his dream of one-step color photography with no additional coatings or layers of packaging to peel and discard.

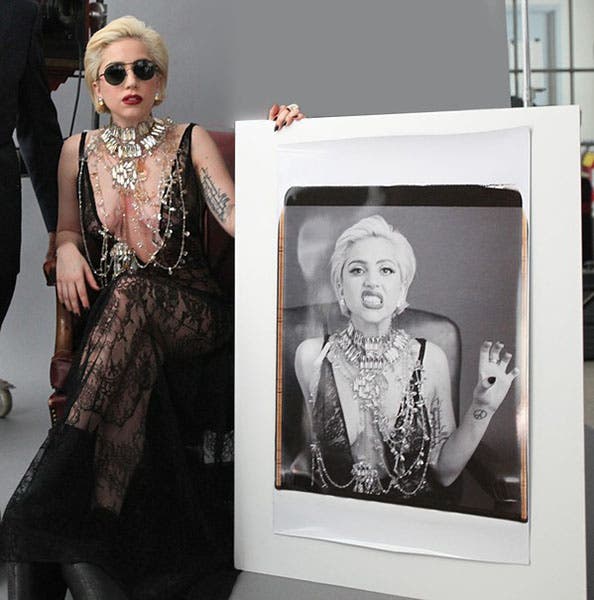

Land remained a major figure at Polaroid until the late-1970s. He hoped to build on the success of the SX-70 through the creation of a home movie system known as Polavision. Despite growing consumer interest in video recording, Polavision was unable to compete with Sony’s Betamax system, which had been released two years earlier. The system’s failure paved the way for Land’s eventual marginalization within the firm. He stepped down as Polaroid’s CEO in 1980 and left the firm completely in 1982. After selling off his company stock, Land established the Rowland Institute, an organization dedicated to fundamental research, where he continued to pursue his interest in optics and color perception. Edwin Land passed away in 1991 before the proliferation of digital photography, and the first of Polaroid’s two subsequent bankruptcies. He was buried near his company’s Cambridge headquarters at Mount Auburn Cemetery, whose designer, Jacob Bigelow, was featured in a recent Scientist of the Day post. Though few of Land’s personal papers survive, in 2010, Polaroid donated a collection of artifacts, photographs, and notes that shed light on his innovative career to the MIT Museum. To celebrate the occasion the company’s newly appointed artistic director, Lady Gaga, posed for a portrait, much as Land himself did at the first demonstration of his instant camera in 1947 (seventh image).

Lady Gaga poses with her Polaroid portrait at the MIT Museum in 2010. (MIT Alumni Association)

Benjamin Gross, Vice President for Research and Scholarship, Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to grossb@lindahall.org.