Scientist of the Day - Don Carlos, Prince of Asturias

Carlos, Prince of Asturias in northwestern Spain, was born July 8, 1545. Don Carlos had no interest in science whatsoever, but his miraculous recovery from a near fatal accident inspired the commission of one of the great automata of the late Renaissance. Here is the story. On Apr. 19, 1562, young Carlos was returning from a late night tryst in his college town of Alcalá when he fell down the stairs of his residence and struck his head. He was semi-comatose for weeks, then developed an infection and went blind, all of which was cause for great consternation, as Carlos was the heir apparent to the throne of Spain.

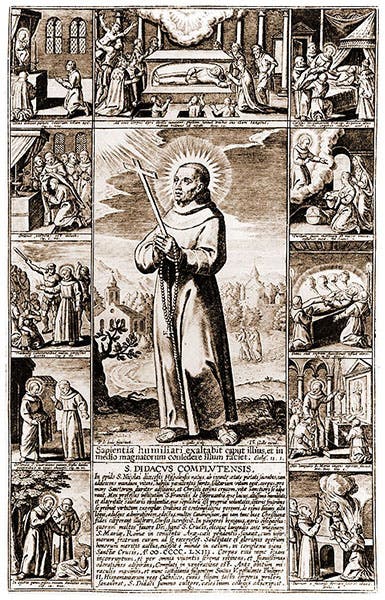

His father, Phillip II, the king apparent, rushed to his son's side and had the best physicians brought in, including the great Andreas Vesalius, who had left Padua to serve the Habsburg rulers. Some accounts say that Vesalius trepanned the young lad's skull to relieve pressure on his brain, although evidence for this is lacking. But all accounts agree that something very remarkable happened on May 9. 1562. The local townsfolk of Alcalá brought in the bodily remains of their rejected candidate for sainthood, Diego de Alcalá. Diego had died nearly one hundred years earlier, but his body, so it was said, was still sweet-smelling and free from corruption. His body was placed next to that of the blind and nearly insensible Don Carlos and the two were brought into physical contact (third image). The prince immediately fell into a profound sleep, and when he awoke the next day, he was on the mend.

Don Carlos being saved by contact with the body of Diego de Alcalá, detail of seventh image (Elizabeth King on blackbird.vcu.edu)

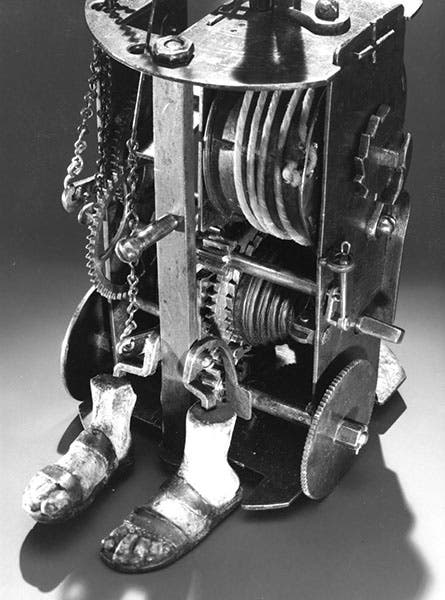

Phillip was so appreciative of the miraculous recovery that he ordered an instrument maker – many think it was the court clock-maker, Juanelo Turriano, whom he had inherited from his father, Emperor Charles V – to construct a mechanical praying monk, in the image of Diego de Alcalá. Turriano (if it was he) was up to the task (first and fourth images). His miniature mechanical monk was about 15" tall and had intricate innards of iron (fifth image).

Detail of the Smithsonian mechanical monk, photograph by Rosemund Purcell (Radiolab at wnyc.org)

The monk would walk in a straight line, beat his chest occasionally while mouthing some silent mea culpa, turn to his right and continue walking, occasionally raising a cross to his lips, and then keep going, eventually tracing out a square path. He was powered by a spring that was wound with a key. The most amazing thing about the automaton is that it still survives in the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution – and it still works! Here is a link to a 4-minute video of automaton Diego doing his thing. For a silent movie, it is compelling viewing.

Detail of the inner workings of the mechanical monk, NMAH, Smithsonian Institution (Radiolab at wnyc.org)

The rest of Don Carlos’ short life was not uneventful. Before his accident, he had been betrothed to Elisabeth of Valois, and then his father Phillip thought better of the match and took Elisabeth for his own wife. This might be fairly traumatic for any young man and perhaps not likely to generate an outpouring of paternal love. We include here a portrait of Carlos painted about the time he learned that his fiancé was soon to be his mother (second image). In 1564, after he had recovered from the accident, Carlos became increasingly irrational, so it was said, or perhaps he was just really ticked off, and he plotted against his father on behalf of the Netherlands, which was resisting Spanish rule. In 1568, Phillip II, fed up, had Carlos sealed up in his room, and after six months of confinement, Carlos died, perhaps because of his deteriorating physical condition, perhaps aided by poison or some other court-ordered intervention. He was only 23 years old.

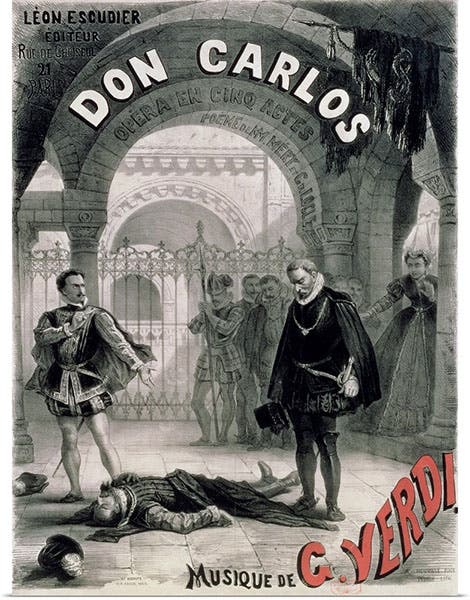

Two hundred and twenty years later, Friedrich Schiller turned Carlos' life story into a play, and 80 years after that, Giuseppe Verdi fashioned the play into an opera, Don Carlos, which premiered in Paris in 1867 (sixth image). The central events of the opera are the loss of Don Carlos' beloved Elisabeth to his father, and Don Carlos' eventual death at the orders of Phillip. The fall down the stairs and the miraculous intervention of Diego de Alcalá are not even mentioned. We feel that Verdi really missed the boat here. The entry of the hundred-years-dead Diego would have made for quite a scene, although presumably Diego would not have had a singing role.

The sanctification of San Diego de Alcalá, engraving by Cornelius Galle, 1614 (Elizabeth King on blackbird.vcu.edu)

Phillip promised the town of Alcalá that he would continue the fight for sainthood for Diego, and this he did, although he had to outlive three popes to accomplish it. But finally, in 1588, Diego was canonized (seventh image). It is a good thing the petition was successful, otherwise the Kanas City Chiefs would have been playing home-and-home series with the Fra Diego Chargers for all those years. Yes, San Diego, California is named after our monk, the one who just wouldn't decay. Don Carlos has yet to attract an NFL franchise.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.