Scientist of the Day - Cyriaco d’Ancona

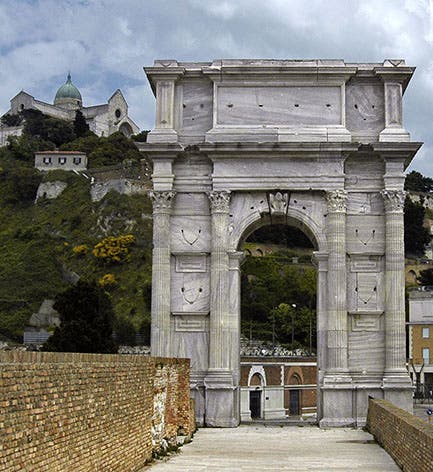

Cyriaco d’Ancona, an Italian merchant and traveler, was born July 31, 1391. Also known as Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli, Cyriaco worked out of his home town of Ancona, a trading center south of Venice on the Adriatic coast. Ancona was no Genoa or Venice, but it was the center of an extensive trade network that included Cyprus, Rhodes, Constantinople, and Alexandria, and Cyriaco travelled to all these places, beginning at a young age, trading for silks, mastic, and spices for his clients back home. So when he had his epiphany in 1421, he was still a young man, age 30, but was worldly-wise and experienced. The epiphanous moment came when he was back home in Ancona, and he noticed the marble arch that stood on the harbor edge (first image). He had passed it by hundreds of time, but he had never really looked at it before this day. He noticed how elegant it was, with its double pair of Corinthian columns, and he realized that it had a lengthy inscription on it. At the time, he could not even read Latin, but he could make out the letters of one name, Trajan, whom he recognized as a Roman emperor of an earlier millennium. Cyriacus was immediately taken with the fact that these stones were a physical connection to an ancient time, and that the Emperor Trajan was speaking to him directly through this monument. Cyriacus had fallen in love with archaeology, a discipline which, at that time, did not exist.

In 1421, Italian humanism was just starting to flourish, and contemporaries like Poggio Bracciolini in Florence were ardently searching for texts of ancient writers such as Cicero. But no one realized that stones could speak as well – no one except Cyriaco, who welcomed his new calling and ran with it to his very last days. In order to read ancient inscriptions, he began to learn Latin, not by taking lessons and studying grammar, but by starting to read Virgil's Aeneid, which he chose because Virgil plays a key role in Dante's Inferno. It was as if a present day Italian decided to learn English by reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. Cyriaco resumed his travels, now with an eye for monuments. He went to Rome, and was appalled by the fact that ancient buildings were either in complete ruins, or were being dismantled for use in other buildings, and in some cases were even being burnt as a source of lime. When he returned to Constantinople, he saw the same thing, a city in historical disarray, with no sense of its glorious past. He decided to try to change this, by persuading Popes and Emperors and Sultans of the importance of preserving the relics of ancient times. And amazingly, during the course of his remaining years, he did become the companion of many of the ruling figures of Europe, including several Popes and the Holy Roman Emperor. Cyriaco was also unusual in extending his archaeological interests to Greece. None of the humanists of the time cared about Greek history – it was the glory of Rome they pursued. In 1436, Cyriacus managed to get to Athens, so that he could see the Parthenon. He was the first person since antiquity to go to Athens for that purpose. He even learned Greek (this time in a more conventional manner), so that he could read Greek inscriptions’ as well as Latin ones.

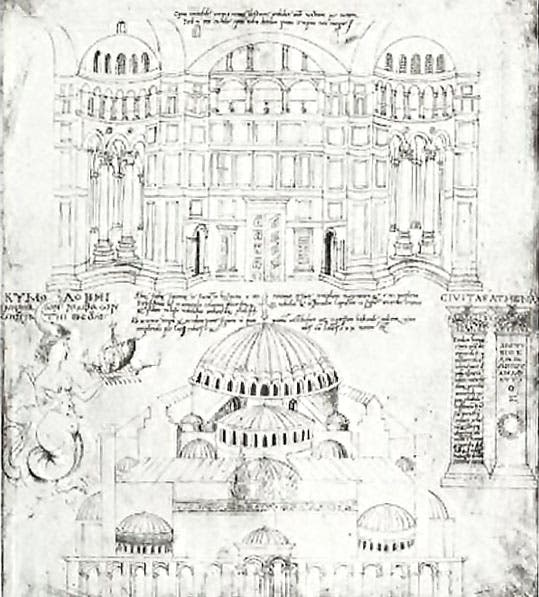

Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, copy of sketch by Cyriaco d’Ancona, 1444 (nauplion.net)

Cyriaco did not have much success in his quest for official sanction for archaeological preservations – the times were too tumultuous, and there were more compelling problems between the Ottomans and the West, and even among the battling Italian states and republics. But Cyriaco did keep a detailed diary for his whole life, transcribing inscriptions, and making careful drawings of antiquities. He filled six fat manuscript volumes with his meticulous notes – he called them his Commentaries. The Commentaries are really the first book of archaeology in the West, and it is because of them, and because of his unique archaeological vision, that Cyriacus is often called the father of archaeology. Unfortunately, the Commentaries were never published (he died before printing was even invented), and the manuscripts perished in a fire in the early 16th century. Fortunately, many of his drawings had been copied by others (third image), so the seeds he cast did bear fruit. And many of his letters survive as well.

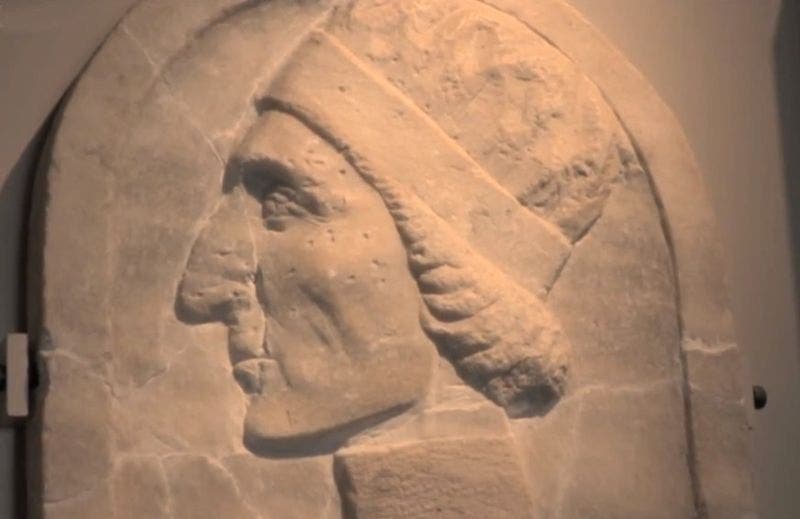

We have only one certain portrait of Cyriacus, a relief in the archaeological museum in Ancona (second image). Recently a historian has claimed to spot another, in the well-known frescoes in the Magi Chapel in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence, painted around 1459 by Benozzo Gozzoli (fourth image). There are a number of figures stacked up on the right of the Procession of the Oldest King, and it is claimed that one of them, a profile at the far right of the second row, represents Cyriaco (fifth image).

The argument that Cyriaco is surely in this fresco cycle is a sound one, since he was involved in the Council of Florence that generated the paintings and knew many of the other people depicted, but there seem to be half-a-dozen profiles in the frescos that resemble the relief as much as the one highlighted, so the reasons for choosing this particular one are not obvious to us. But we will leave this matter in the capable hands of Cyriaco scholars. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.