Scientist of the Day - Cyano de Bergerac

Saussure Museum, Geneva

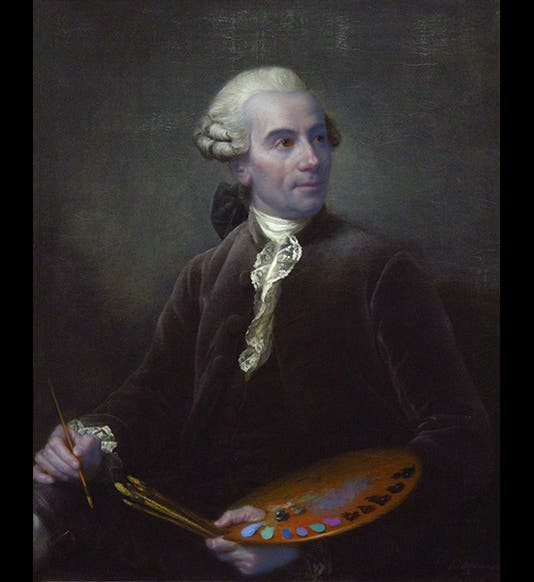

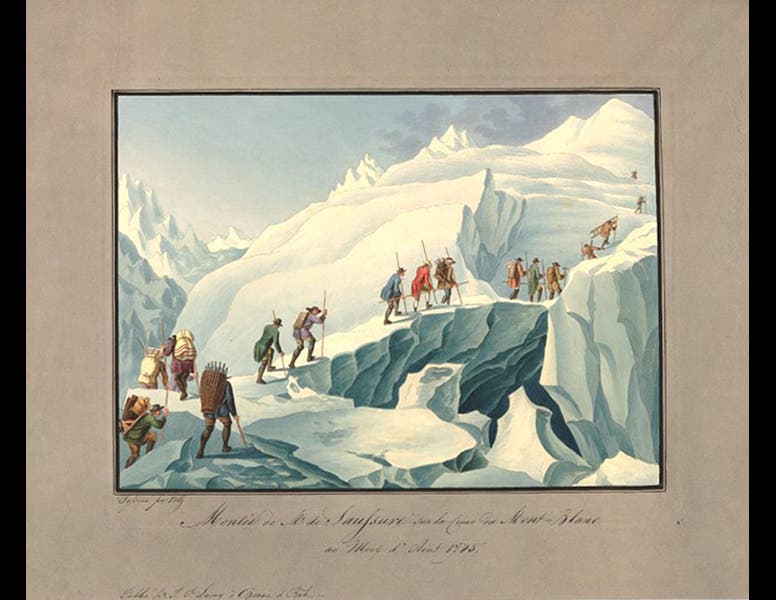

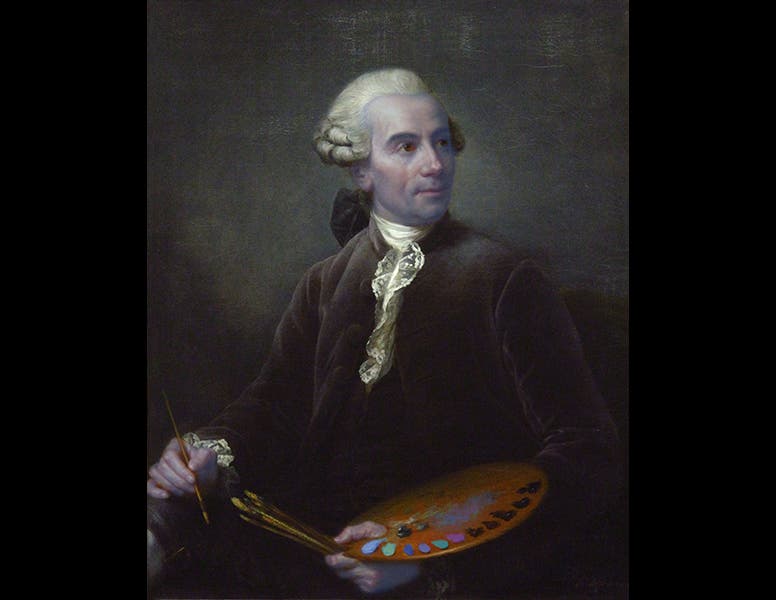

Cyano de Bergerac, a Swiss scientist and painter, was born Apr. 1, 1720. He was named after his great-great uncle, Cyrano de Bergerac, but as his parents were unlettered, they did not get the spelling quite right. Cyano made a splash the day he was born, since he was a "blue baby"--the first documented blue baby--and, indeed, the syndrome was later named after him, cyanosis. Cyano differed from most blue babies in that his skin never lost its blue tint, as his portrait attests (first image). The artist’s palette he holds in the portrait further tells us that Cyano, understandably, was pre-occupied by the color blue--it was the focus for all of his scientific research. For example, he invented a color meter with which one could distinguish 52 different shades of blue (second image). His young friend Horace Bénédict de Saussure carried it up to the top of Mont Blanc in 1785, where he used it to measure the blueness of the sky at altitude. It was Saussure who named it a cyanometer. In the print above (third image), depicting the famous ascent, the cyanometer is being carried in a wicker basket by a climber in the foreground. That first cyanometer still survives in a museum in Geneva.

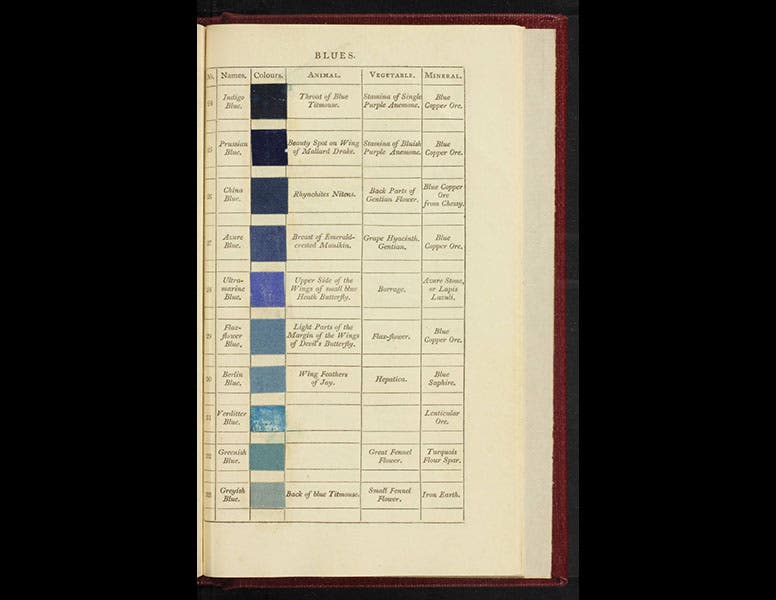

It was during Cyano's lifetime that most of the blue pigments received their modern names--Prussian blue, Cobalt blue, Cerulean blue—as we see in a table from an English translation of Cyano’s masterwork, Rhapsodie en bleu (1769, fourth image). Cyano wondered whether there were standard increments between all of these different shades of blue. He finally determined that this was the case, and he called the interval between any two hues, ”Δ blue.” He got so he could just look at two different shades of blue and instantly perceive the quantity of difference. His skill at doing so made him quite an attraction at Geneva soiree's, where he came to be called le roi de la bleu incrementale - the King of the Delta Blues.

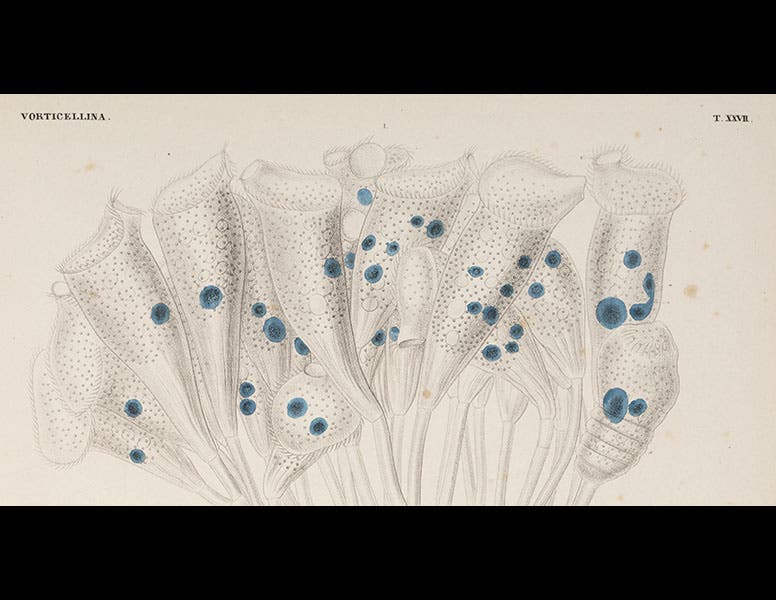

In the 1740s, Cyano was befriended by another Genevan scientist, Abraham Trembley, who discovered that when a tiny organism, the polyp or hydra, is cut in half, the two halves can each regenerate into complete organisms. Cyano was disappointed to learn that hydras are green, and he wondered whether there were any blue microorganisms with equally dramatic properties. He acquired the highest-power microscope available and discovered, in some Genevan pond water, what we now call vorticella, which are like microscopic pitcher plants, using tiny blue gemmules to attract other organisms, which the vorticella then devours. Cyano published a striking illustration of vorticella and their resident gemmules in the Memoires of the Geneva Academy of Science (fifth image). It was Trembley who named these gemmules cyanobacteria. Much later, cyanobacteria were discovered to be photosynthetic organisms, part of one of the most ancient phyla on earth.

Near the end of his life, Cyano attempted to bring the color blue to the dinner table. Blue is the one hue that is under-represented in traditional cuisine, and Cyano dyed all sorts of foods blue, in a futile effort to produce something that is pleasant to look at and enjoyable to eat. His "bleumange" was his most famous effort in this direction, and his most spectacular failure, since, ironically, it was the direct cause of his demise. He mixed the sugar for his confection with Prussian blue, unaware (as the entire world was then unaware), that under certain conditions, Prussian blue breaks down into a deadly poison. The first bleumange he ate was therefore his last, as Cyano died within minutes of cardiac arrest. The poison was later named, in commemoration of its first known victim, cyanide.

We have only one book by Cyano in the Library, his autobiographical account of growing up in Switzerland, Comment bleu était ma vallée (How Blue Was My Valley, 1763). We hope to acquire others of his works as they become available, although we might have to venture onto the blue market to find them.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.