Scientist of the Day - Charles Dawson

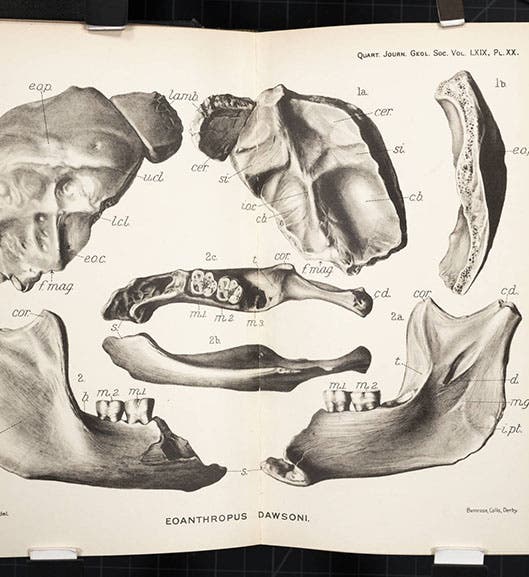

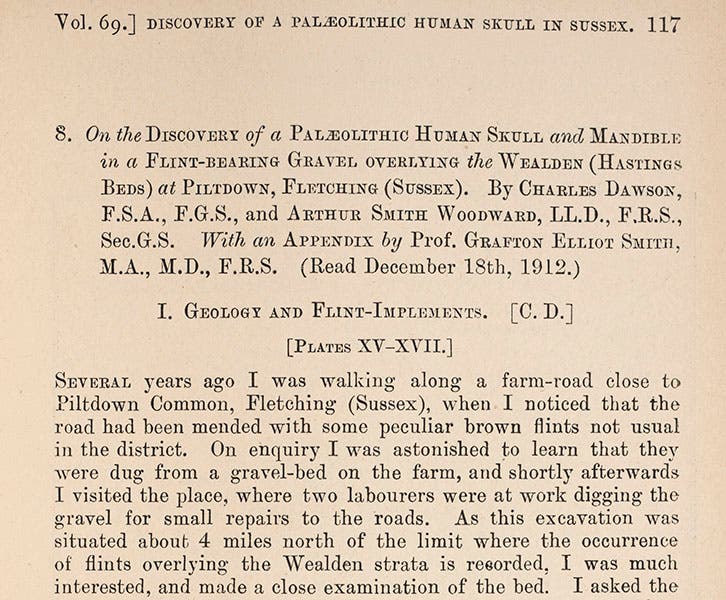

Charles Dawson, an English barrister and amateur antiquarian, was born July 11, 1864. Although he lacked any formal scientific education, Dawson managed to get elected to both the Geological Society of London and the Society of Antiquaries, on the strength of various fossils and antiquities that he found at assorted sites in Sussex in the 1890s. But his big moment came in 1912, when he discovered fragments of an ancient human-like skull at a gravel pit in Piltdown. Summoning expert help from London in the form of Arthur Smith Woodward, Dawson then, in front of his witness, pick-axed a primitive human jaw bone out of the gravel. The next year, Woodward put the pieces together to form a skull, and he announced that Piltdown man was an ancestral human species, which he named Eoanthropus dawsonii, “Dawson’s dawn human”. The paper was published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London under the unwieldly title: “On the discovery of a Palaeolithic human skull and mandible in a flint-bearing gravel overlying the Wealden (Hastings beds) at Piltdown, Fletching (Sussex)" (second image), with a suite of engraved plates illustrating the Piltdown fragments (first image).

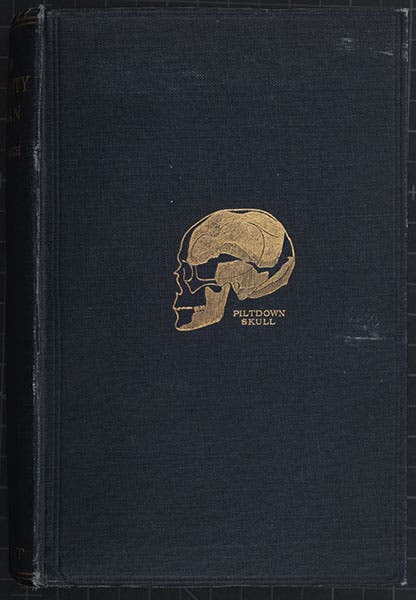

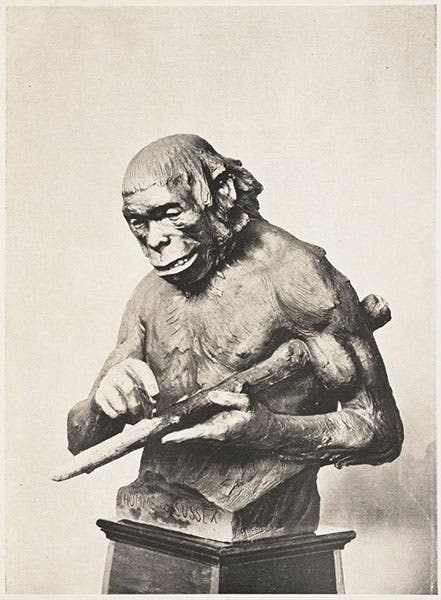

Piltdown man was immediately given a prominent place in the human family tree. When Arthur Keith published his The Antiquity of Man in 1915, the Piltdown fragments were embossed in gold right on the cover (third image). When Aimé Rutot and Louis Mascre collaborated to sculpt 10 human ancestors in bronze in 1914 and put them on display, the "Man from Sussex" shared the stage along with Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon. (fourth image).

Piltdown man reigned in English anthropological circles right up until 1953, when it was abruptly revealed to be a fake. The jaw, for example, turned out to be a modern orangutan jaw that had been artificially stained to look old, with its teeth carefully filed down to resemble human teeth (fifth image). The skull fragments were those of a not-so-ancient human, also carefully stained.

As anthropologists cast about for culprits (the principals were all dead by that time), they looked first at Dawson, since he had found most of the bones, but he was initially rejected as the miscreant, since everyone assumed that he, as an amateur, would not have had the skills and expertise to fabricate such a clever hoax. Attention focused instead on a variety of figures, including Woodward, Keith, the Abbé Teilhard de Chardin, and even Arthur Conan Doyle.

Recent investigations, however, have returned the focus to Dawson. It has been discovered, for example, that most of the archaeological finds Dawson made in the 1890s and 1900s were also faked in one way or another. It is now considered almost certain that Dawson was the perpetrator of the Piltdown fraud, and that he had a lot more skills than we thought, although he used them unethically. Dawson’s motive seems to have been to gain admission as a Fellow to the Royal Society of London, which had denied him membership several times. Dawson died suddenly, in 1916, before the Royal Society could bestow that honor, saving them the trouble of revoking it later.

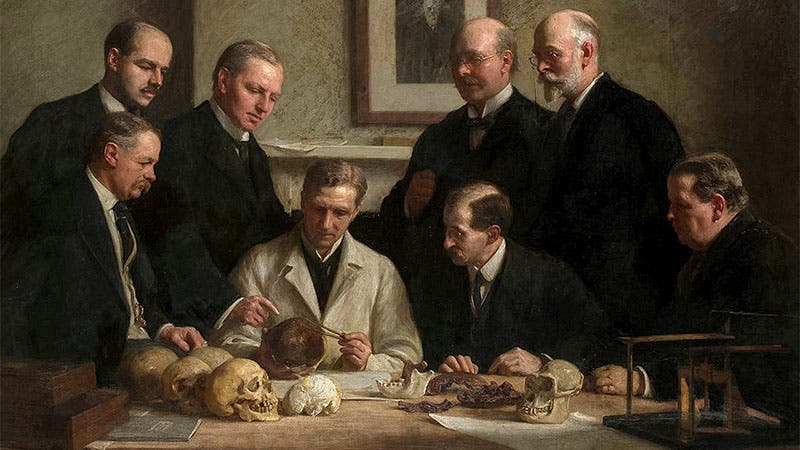

Since Dawson was a scientific scoundrel, we will not reward him with a full portrait, but we will point out that in the famous group portrait of the British anthropological establishment admiring the Piltdown specimen, a portrait that hangs in the Geological Society of London (sixth image), Dawson is in the back row, second from the right, partly eclipsing a portrait of Charles Darwin. We displayed the Piltdown paper by Dawson and Woodward in our 2012 exhibition, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity, along with works by William King Gregory, Keith, and Rutot on Piltdown; they are shown in succession, starting here. An exhaustive and incredibly detailed re-examination of the Piltdown remains by 16 experts in a variety of disciplines was published in 2016. If you would like to learn every last possible detail about Dawson’s forgeries, click here. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.