Scientist of the Day - C. T. R. Wilson

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

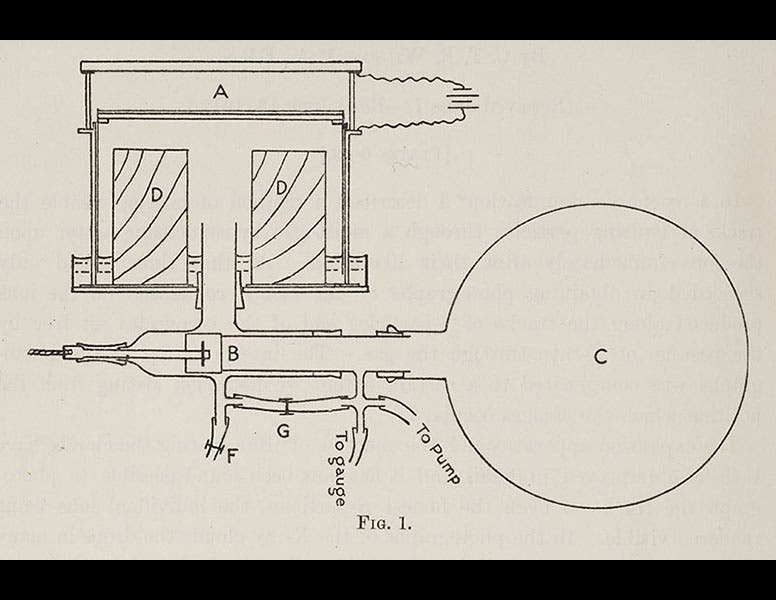

Charles Thomson Rees Wilson, a Scottish physicist better known as C. T. R. Wilson, was born Feb. 14, 1869. In his early career at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, Wilson was interested in meteorology, and in particular, in cloud formation. He found that if he saturated a small clear chamber with moisture, and then rapidly expanded the cylinder by means of a piston, a small cloud would form in the chamber. He had invented the cloud chamber.

Twenty years later, Wilson discovered another use for his invention. His colleagues at the Cavendish, such as Ernest Rutherford, were attempting to probe atomic interiors, primarily by using alpha particles, which radioactive radium provided in abundance. But the only alpha particle detector available was something called a scintillation screen, which produced a tiny blip (a scintillation) when struck by an alpha particle. It was a limited detector, at best.

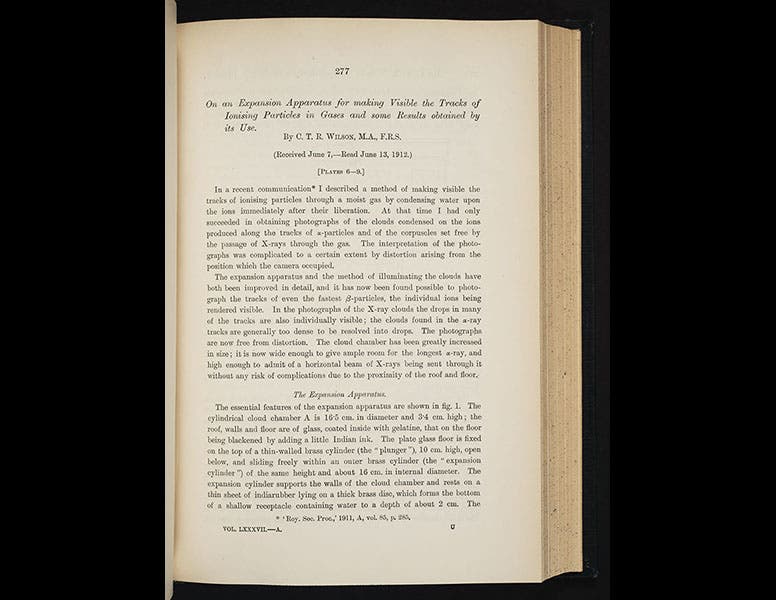

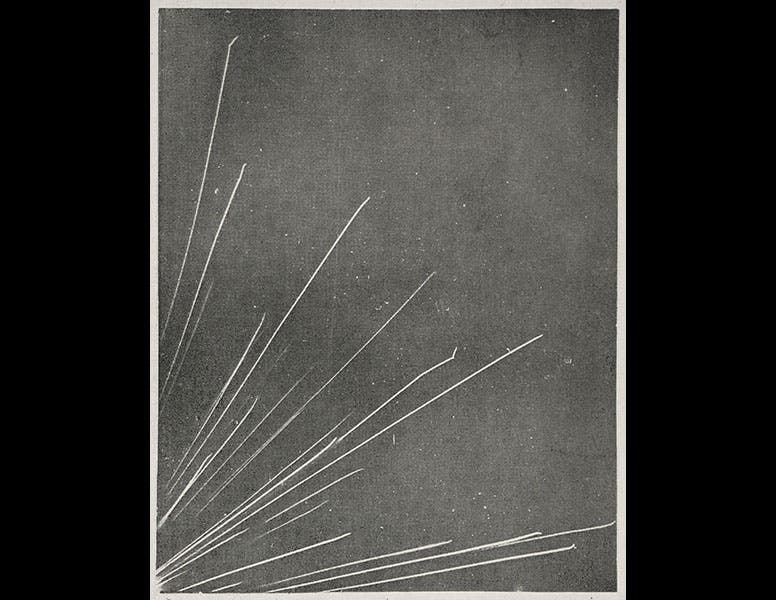

In 1911, it occurred to Wilson that his cloud chamber might also be useful as a particle detector. He found that if he placed the chamber in the path of a radioactive source, then as the cloud formed, any charged particles passing through the chamber would make long tracks that recorded their passage. The tracks would quickly dissipate, but if they were photographed a split second after cloud-formation, the particle tracks could be permanently recorded on film. Wilson announced the new use for his invention in a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London in 1912 (second image). The paper included a diagram of his apparatus (third image), as well as photographic plates recording the paths of alpha particles through the chamber (fourth image).

The Wilson cloud chamber, as it came to be called, would prove indispensable as physicists began to discover new particles. Rutherford used it to discover, in 1919, that if you shot alpha particles into a container of nitrogen gas, occasionally one would strike a nitrogen nucleus and produce an oxygen atom, with a particle left over--one that had a positive charge and the mass of a hydrogen atom. Rutherford had discovered the proton.

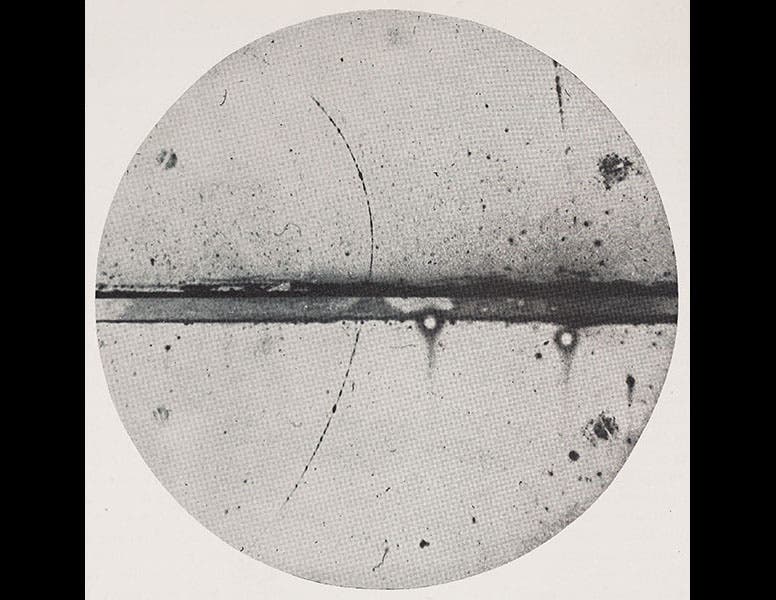

In 1932, Carl Anderson was looking for evidence of antimatter, which had been predicted several years earlier by Paul Dirac. Anderson observed the interactions of high-energy cosmic rays in a cloud chamber, which he had surrounded with a magnetic field, so that negatively-charged particles would curve to the right and positively-charged ones to the left. He put a lead plate in the middle of the field, which would slow down any particle that went through it and cause it to curve more, a clever way to tell which direction the particle was going. With his cloud chamber, he recorded a charged particle, coming in from the bottom, which encountered the lead plate and emerged with a strong curvature to the left (fifth image). The amount of curvature yielded the charge-to-mass ratio, revealing that this was a particle with the mass of the electron, but a positive charge. It was a positive electron, an anti-electron, or, as it was soon dubbed, a positron. Wilson's cloud chamber was instrumental in its discovery.

Wilson received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his invention. One of Wilson's original cloud chambers is on display in the Cavendish Laboratory Museum at Cambridge (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.