Twelve Thousand Volumes Under the Sea: Books from the Library of Captain Nemo

In March 1869, Jules Verne published the first installment of Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea). The book introduced Captain Nemo, who abandons the surface world to explore the ocean depths in his remarkable submarine, the Nautilus. This exhibition features some of the volumes in Nemo’s library, along with works related to landmarks that he encounters during his travels.

Verne initially revealed almost nothing about Nemo’s origins. Only in a sequel, L'Île mystérieuse (The Mysterious Island, 1874-75), would readers discover that the captain was actually Prince Dakkar, an Indian nobleman who took to sea following his family’s death in the 1857 revolt against the British. The original novel did, however, provide a few details about Nemo’s education.

The captain recalls that before forsaking life on land, he studied engineering in Europe and America, which enabled him to build his submarine. He also accumulated an extensive personal collection of books, which he brought onboard the Nautilus. By including references to real-world scientists and engineers, Verne provided a factual basis for his otherwise fantastic narratives and implied that industry might one day match—or even exceed—Captain Nemo’s technological achievements.

Items featured in this exhibition:

Jules Verne

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers

Paris, c. 1877

On loan from LaBudde Special Collections, Miller Nichols Library, UMKC

Jules Verne, Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, 1877

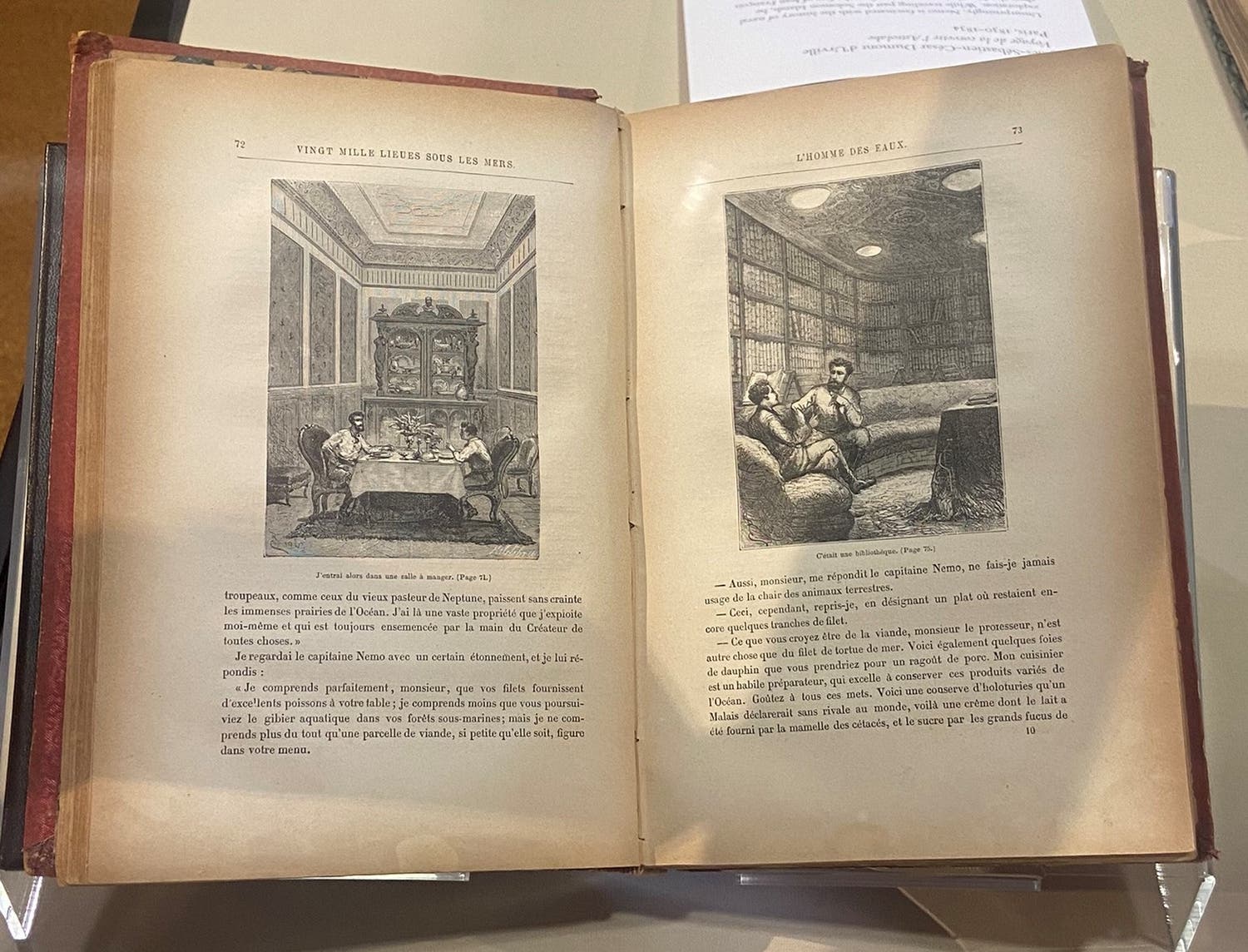

The narrator of Verne’s novel is Pierre Aronnax, a Parisian naturalist who joins a U.S. Navy expedition tasked with hunting a mysterious creature that threatens global shipping lanes. On the evening of November 6, 1867, Aronnax and two companions—his assistant, Conseil, and Canadian whaler Ned Land—are thrown into the Pacific Ocean when their ship collides with what they believe is a gigantic narwhal. They soon discover that their quarry is a submarine and are captured by Captain Nemo.

At first, Aronnax protests his imprisonment, but his attitude softens after Nemo grants him access to the Nautilus’ magnificent library, depicted in this wood engraving by Edouard Riou. Among the twelve thousand volumes that line its rosewood shelves are major works related to mechanical engineering, meteorology, geography, and natural history.

Joseph Bertrand

Les foundateurs de l’astronomie moderne

Paris, 1865

Joseph Bertrand, Les foundateurs de l’astronomie moderne, 1865

In a conversation with Aronnax, Nemo describes his books as “my only ties with the shore” and notes that he stopped adding titles to his library once his submarine became operational. The captain never specifies the date of the Nautilus’ maiden voyage, but Aronnax deduces that it could not have occurred earlier than 1865 since Nemo owns a copy of this history of astronomy by the French mathematician Joseph Bertrand.

Coincidentally, Bertrand’s book was published by Jules Verne’s long-time collaborator, Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Hetzel was the editor of Magasin d’éducation et de récréation, the family-oriented periodical where Vingt mille lieues sous les mers was first serialized

Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville

Voyage de la corvette l'Astrolabe

Paris, 1830-1834

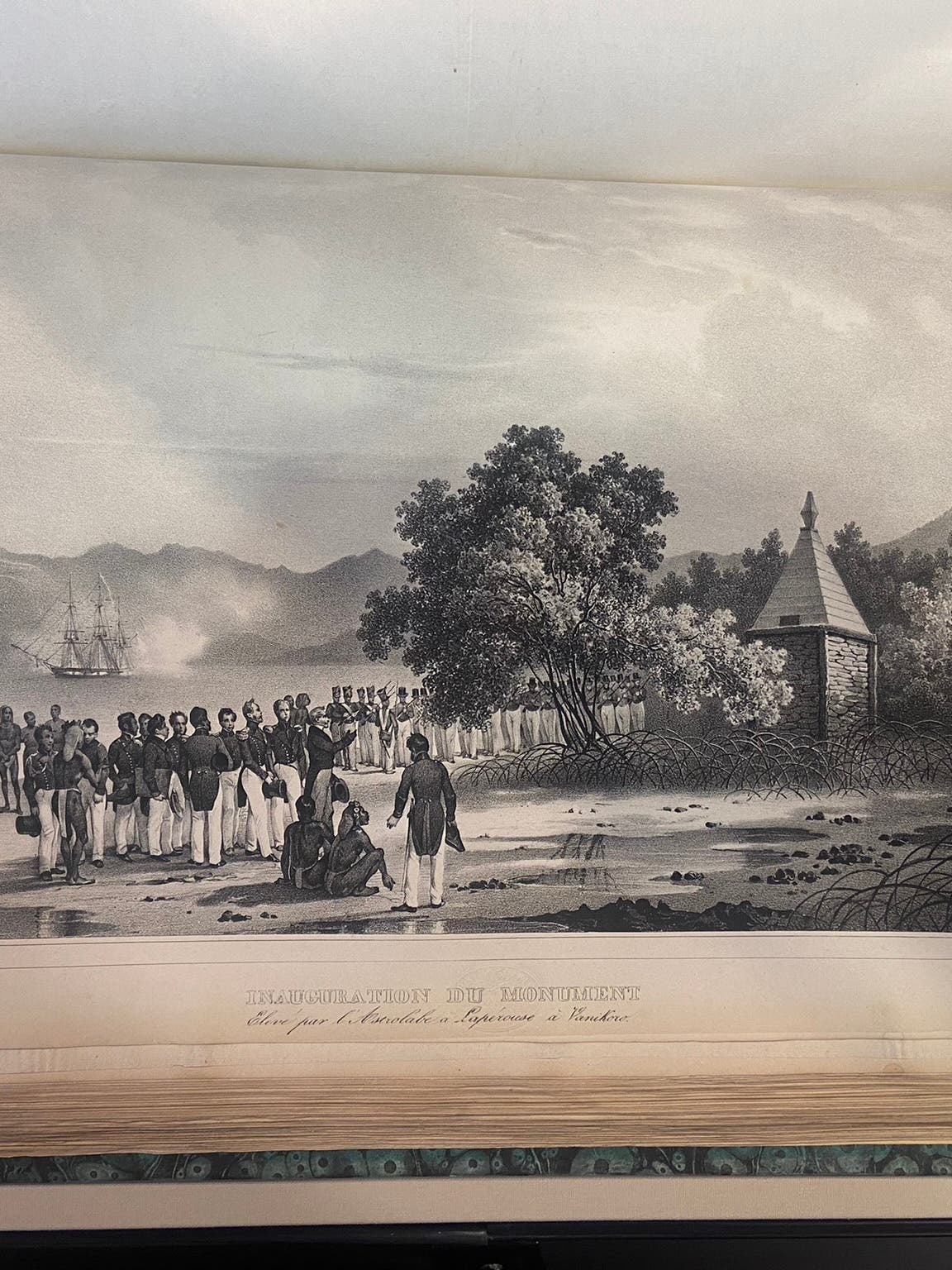

Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville, Voyage de la corvette l'Astrolabe, 1830-1834

Unsurprisingly, Nemo is fascinated with the history of naval exploration. While traveling past the Solomon Islands, he alters the Nautilus’ course to confirm the fate of Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse.

Lapérouse was the leader of a scientific expedition that left France in 1785 and visited Easter Island, Australia, and Alaska before disappearing three years later. In 1828, another explorer, Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville, confirmed that Lapérouse’s two ships ran aground near the island of Vanikoro and built the memorial seen here. The inhabitants of Vanikoro recalled that Lapérouse attempted to escape the island by building another boat, but Dumont d’Urville could not verify their claims. Nemo, undoubtedly familiar with Dumont d’Urville’s account, successfully locates the coral-encrusted wreck of Lapérouse’s third ship off the coast of Guadalcanal.

Ferdinand de Lesseps

The Isthmus of Suez Question

London, 1855

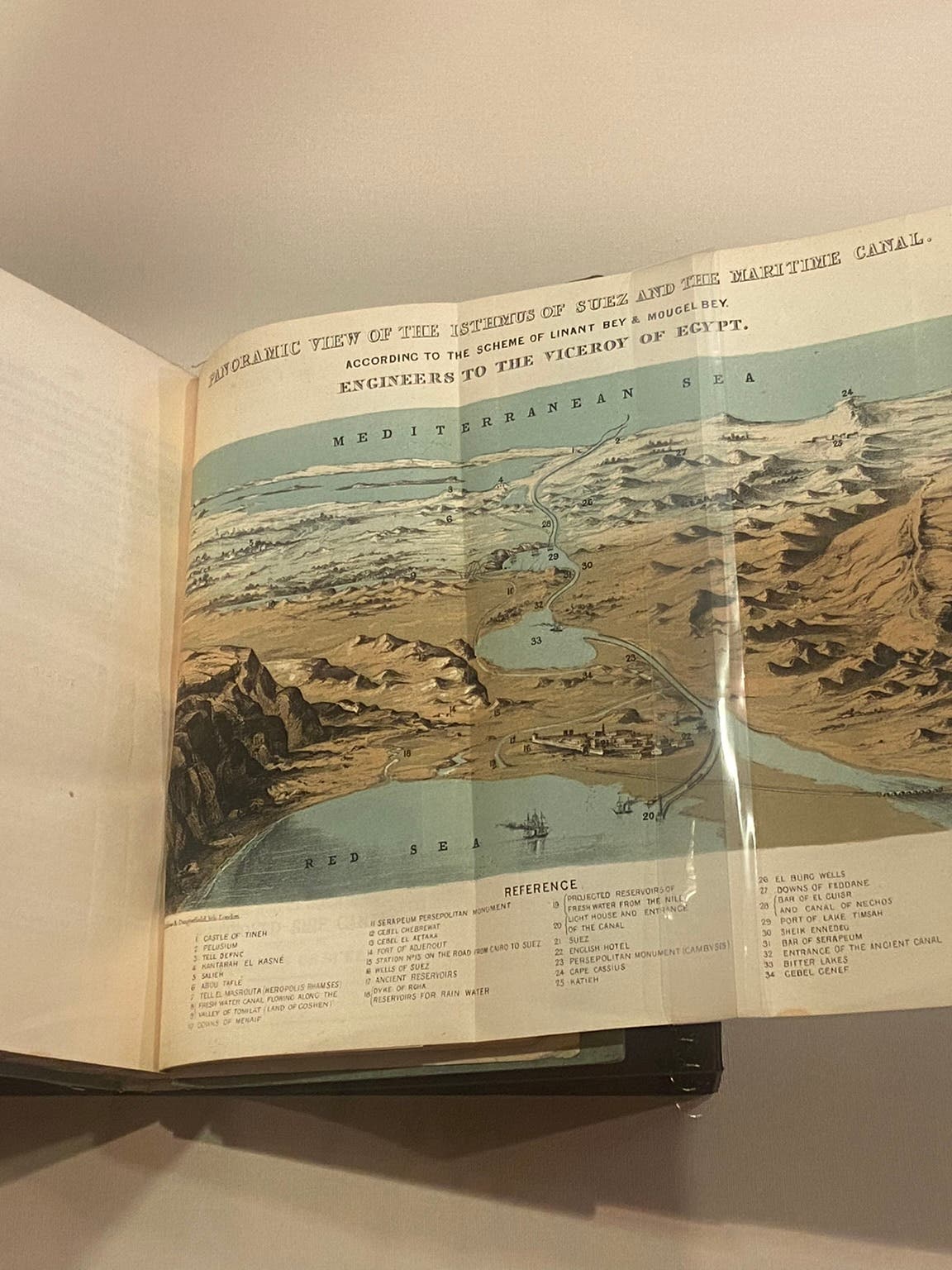

Ferdinand de Lesseps, The Isthmus of Suez Question, 1855

Nemo’s disdain for civilization leaves him reluctant to compliment anyone who chooses to live on land. He makes one noteworthy exception in February 1868, when the Nautilus enters the Red Sea. After Aronnax calls attention to the imminent completion of the Suez Canal, Nemo surprises him by echoing his praise for Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French diplomat overseeing the project. “Such a man brings more honor to a nation than the greatest generals!” the captain observes.

Aronnax suspects that Nemo views de Lesseps as another misunderstood visionary, and this 1855 pamphlet certainly reinforces that characterization. Intended to boost British support for a canal linking the Red and Mediterranean Seas, it instead inspired complaints about its high cost and technical difficulty. Undaunted, de Lesseps spent the next four years securing funding for the project and another decade after that supervising the canal’s construction.

Matthew Fontaine Maury

The Physical Geography of the Seas

New York, 1855

Matthew Fontaine Maury, The Physical Geography of the Seas, 1855

Of all the authors represented in the Nautilus’ library, the one most frequently referenced in Vingt mille lieues sous les mers is the American oceanographer, Matthew Fontaine Maury. As the head of the U.S. Naval Observatory, Maury analyzed data from ships’ logs to produce detailed meteorological and navigational charts. Nemo and Arronax discuss his popular 1855 book while considering the origins of ocean currents like the Gulf Stream.

Early in his captivity, Aronnax wonders if Nemo is “one of those scientists like the American Maury, whose career had been shattered by a political upheaval.” This description downplays how Maury’s personal beliefs contributed to his professional marginalization. Maury felt that slavery was important to America’s economic future, and after the outbreak of the Civil War, he resigned his commission and joined the Confederate Navy.

William Howard Russell

The Atlantic Telegraph

London, 1865

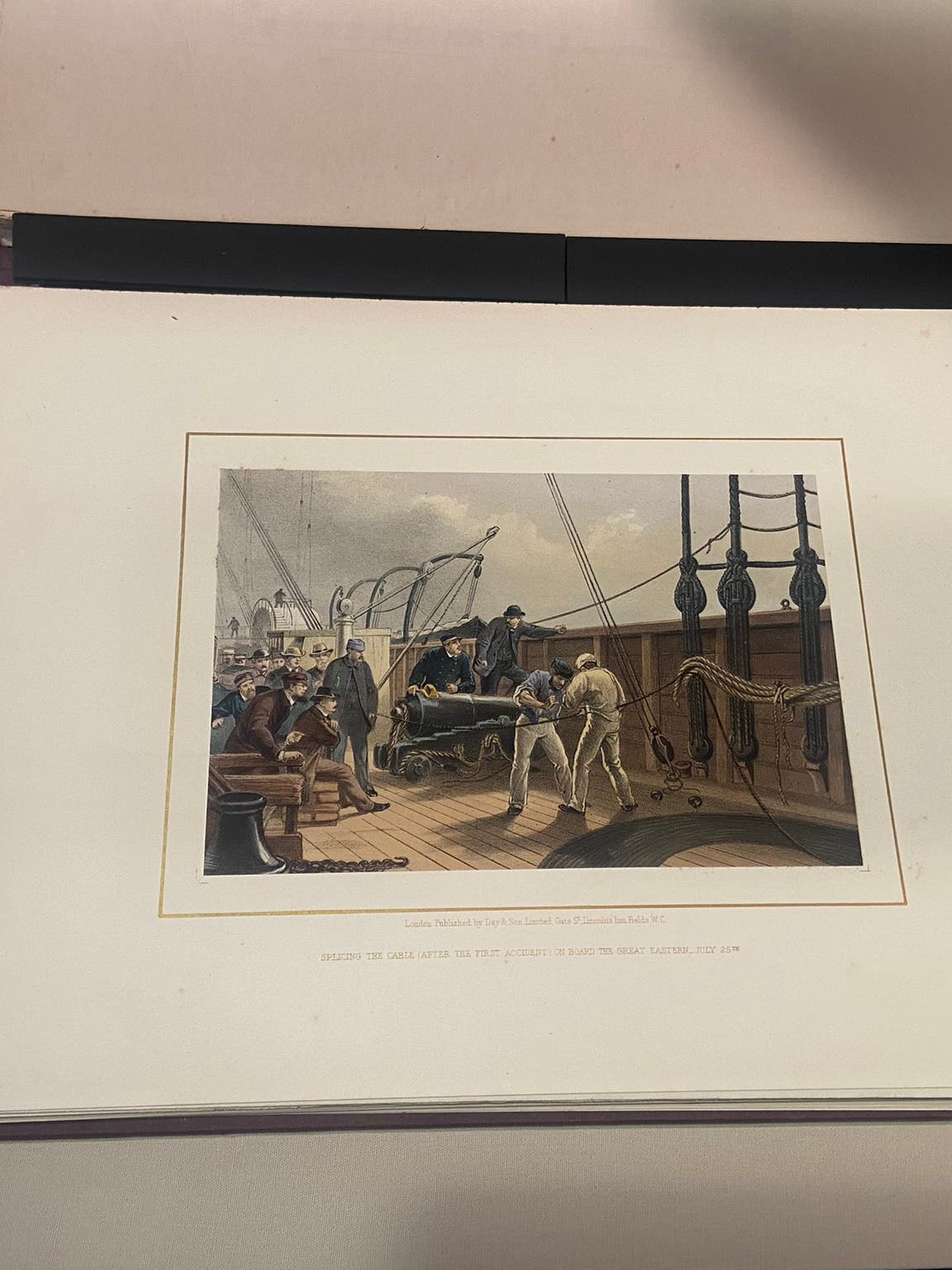

William Howard Russell, The Atlantic Telegraph, London, 1865

Nemo was not the only technological innovator who relied on Maury’s oceanographic data. In 1854, the American entrepreneur Cyrus Field contacted Maury about the feasibility of constructing a transatlantic telegraph cable. Maury responded that recent deep-sea soundings revealed a shallow plain between Newfoundland and Ireland which could provide an ideal route for that project.

During an underwater crossing of the Atlantic in May 1868, Nemo changes heading to follow the “telegraph plateau,” allowing his passengers to witness this ambitious engineering project firsthand. It had taken three attempts before Field and his backers established reliable transatlantic communications. The first cable malfunctioned shortly after its completion in 1858, while the second snapped in the summer of 1865. This lavishly illustrated volume, published in December 1865, presents the official history of both efforts and accurately predicts that the third cable would be fully functional by the end of the following year.

Olaus Magnus

Historia delle genti et della natvra delle cose settentrionale

Venice, 1565

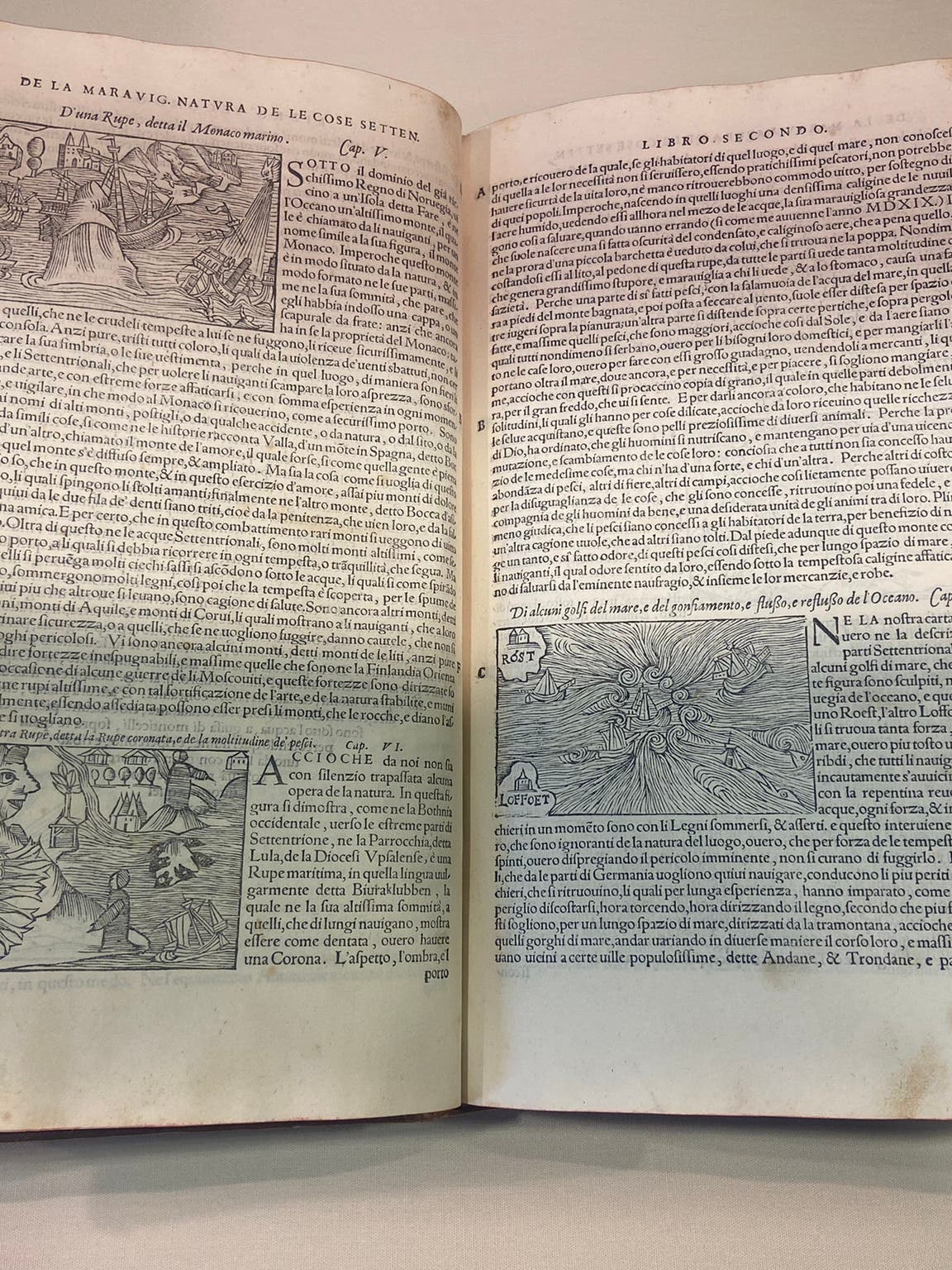

Olaus Magnus, Historia delle genti et della natvra delle cose settentrionale, 1565

After seven months on board the Nautilus, Aronnax’s feelings toward Nemo sour when he witnesses the captain’s brutal assault on a pursuing warship. He, Conseil, and Ned Land find an opportunity to escape when Nemo steers the Nautilus through the Moskstraumen, a series of violent whirlpools off the coast of Norway. (In an 1841 short story, Edgar Allan Poe referred to this phenomenon as the Maelström, the name by which it is better known today.)

Though he may have sailed into the vortex unintentionally, Nemo was likely aware of its existence, since it was featured in Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (A Description of the Northern Peoples), a well-known history of Scandinavia published in 1555 by Swedish writer Olaus Magnus. This 1565 Italian translation features a woodcut of the Maelström and the nearby Lofoten Islands, where Aronnax and his companions are rescued after fleeing the Nautilus. Nemo’s fate remains unknown…until the sequel!

Shipwrights had attempted to construct boats capable of traveling underwater long before Jules Verne introduced readers to Captain Nemo. This exhibition also highlights some of the inventors who inspired the creation of the Nautilus, which in turn served as the namesake for the world’s first nuclear submarine.

Submarines Before and After the Nautilus

Pierre-Alexandre-Laurent Forfait

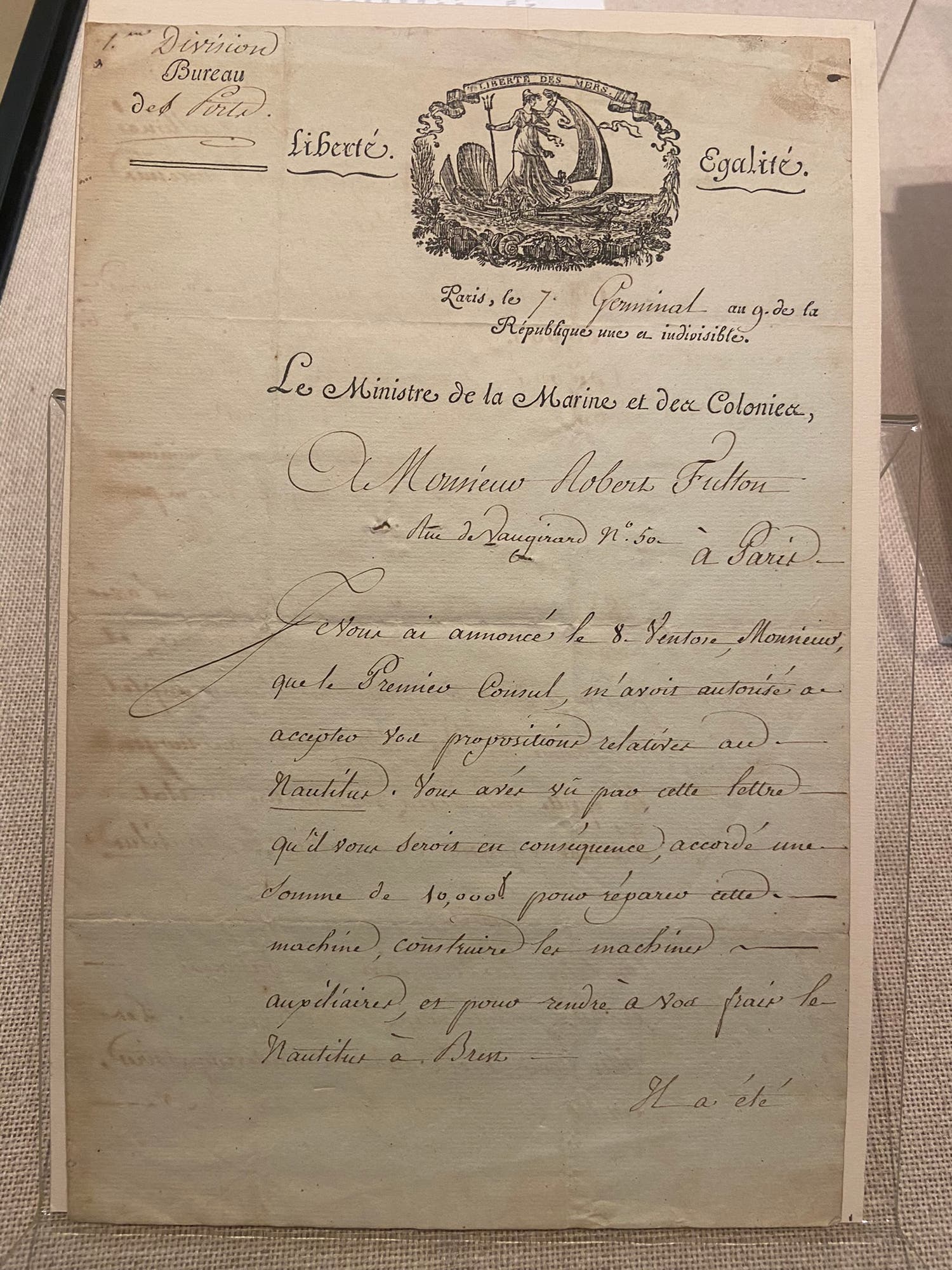

[Letter to Robert Fulton]

7 Germinal IX [March 28, 1801]

Letter from Pierre-Alexandre-Laurent Forfait to Robert Fulton, 1801

Prior to developing the steamboats that would make him famous, the American engineer Robert Fulton spent several years constructing a human-powered submarine. He felt that his “plunging boat,” which he named the Nautilus, would guarantee freedom of the seas by rendering Europe’s warships useless.

Fulton eventually persuaded the French government to invest in his invention to counter the threat posed by the British navy. This letter, written by Napoleon’s first Minister of the Navy—or, as the position was then known, Minister of the Marines and Colonies—outlines the terms of that support. Despite several successful trial dives, Fulton was unable to sink any enemy ships before the Treaty of Amiens led to a pause in hostilities between Britain and France in 1802. He scuttled the Nautilus but remained interested in submarine warfare for the rest of his life.

Murray Fraser Sueter

The Evolution of the Submarine Boat, Mine, and Torpedo, from the Sixteenth Century to the Present Time

Portsmouth, 1908

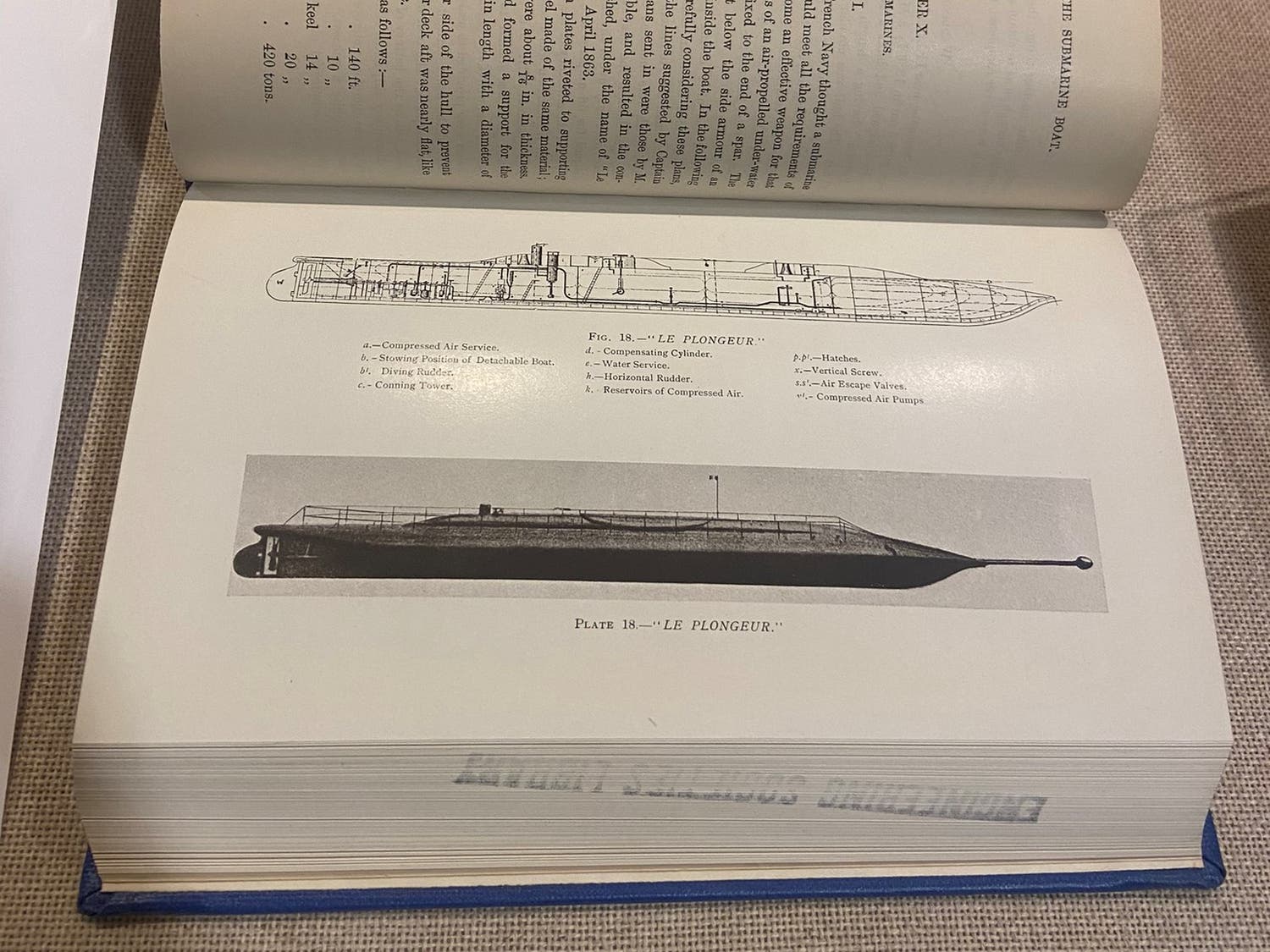

Murray Fraser Sueter, The Evolution of the Submarine Boat, Mine, and Torpedo, from the Sixteenth Century to the Present Time, 1908

Jules Verne started drafting the manuscript for Vingt mille lieues sous les mers after the American Civil War, the first conflict where both sides embraced submarine warfare. In 1864, the CSS Hunley became the first submarine to destroy an enemy warship. The U.S. Navy’s first submarine, the Alligator, was designed by a French immigrant named Brutus de Villeroi, who previously taught mathematics in Verne’s hometown of Nantes.

Neither of these ships served as a model for Nemo’s Nautilus. Instead, Verne likely drew inspiration from the Plongeur, a French submarine launched in 1863. Unlike the Hunley and Alligator, this vessel used compressed air rather than human power for propulsion. Although poor maneuverability limited its military utility, Verne saw a model of the Plongeur at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris. That experience, along with the fair’s aquarium and electricity exhibitions, shaped his perspectives on the undersea world and the technologies required to explore it.

Clay Blair

The Atomic Submarine and Admiral Rickover

New York, 1954

Clay Blair, The Atomic Submarine and Admiral Rickover, 1954

During the first half of the 20th century, the world’s leading naval powers expanded their submarine fleets. These vessels used diesel engines to move on the surface and charge the electric batteries that powered their propellers once they dove beneath the waves. Since those engines could not be run underwater, there were limits to how long a boat could remain submerged.

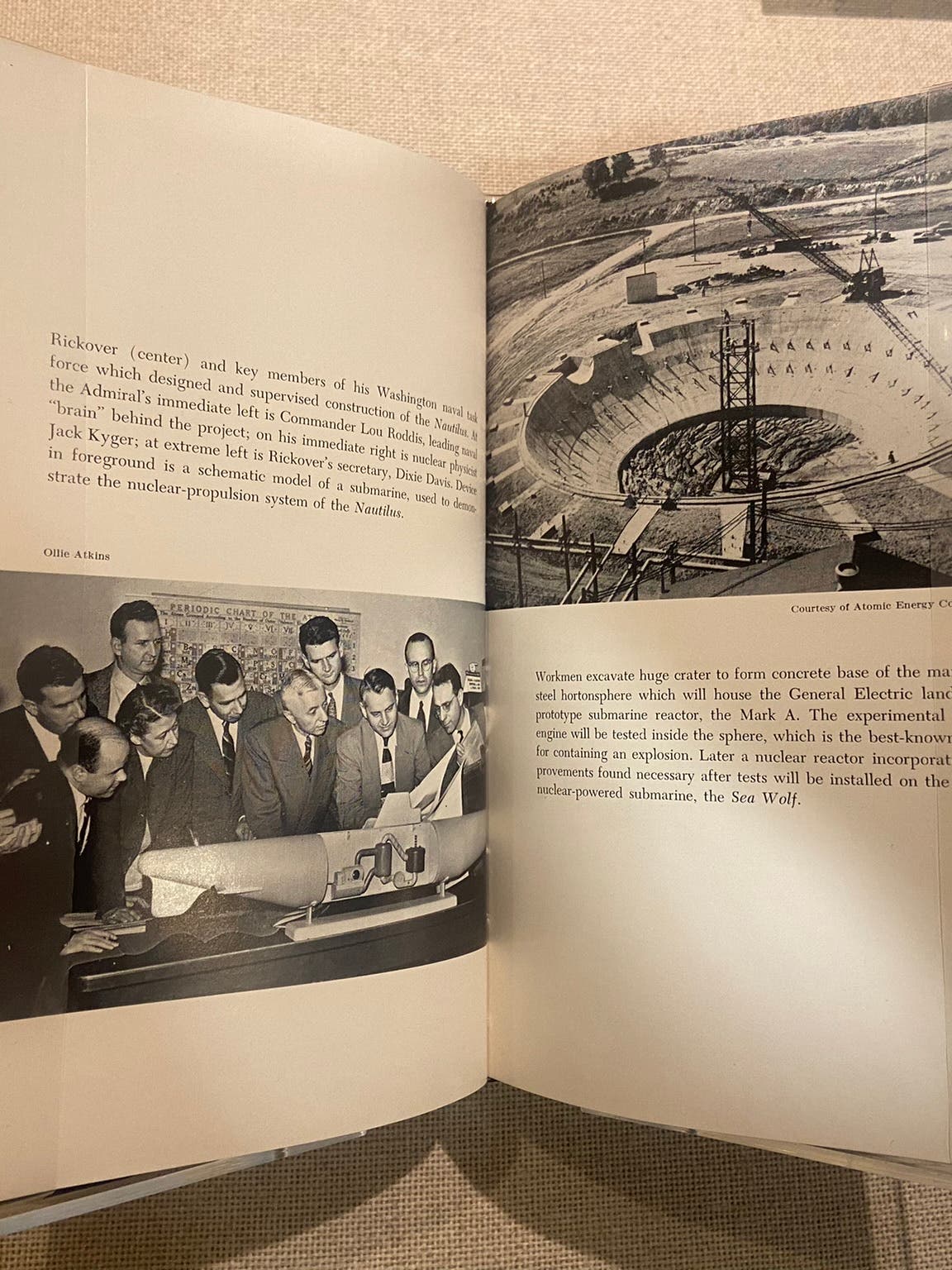

The introduction of nuclear power after World War II allowed engineers to overcome these restrictions. Under the leadership of U.S. Navy Admiral Hyman Rickover, construction of the world’s first nuclear submarine began in 1952. Sharing a name with Fulton’s real-life ship and Nemo’s fictional one, the USS Nautilus launched in 1954 and quickly broke numerous speed and performance records. Most famously, during 1958’s Operation Sunshine, the Nautilus became the first vessel to travel under the Arctic icecap and reach the North Pole.

The Linda Hall Library holds one of the best collections of rare printed science, technology, and engineering works in the world. Each month, our History of Science experts will curate a special collection of rare books for Library visitors to enjoy. This month’s display, Twelve Thousand Volumes Under the Sea, will be on display in the Library’s West Exhibit Hall through September 2022.

The Library is open to the public free of charge during regular Library hours, Monday – Friday, 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.