The World's Fabric

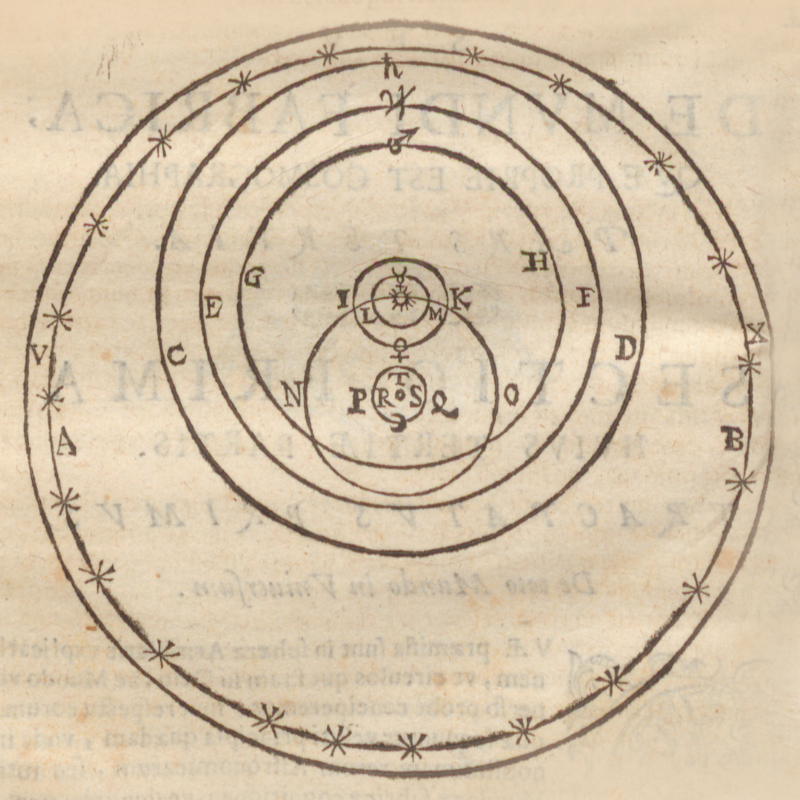

In the 1600s, debate over the nature of the solar system created significant upheaval in European astronomy. World systems with different arrangements of celestial bodies were a major flashpoint. The system advanced by Tycho Brahe asserted that the Moon and Sun orbit the Earth and all other planets orbit the Sun. The Tychonic system was an extension of the Aristotelian or geocentric system, in which the Earth was the center of the solar system with the Sun, Moon, and planets orbiting it. The Copernican or heliocentric system, meanwhile, positioned the Moon in orbit around the Earth, and the Earth and other planets in orbit around the Sun. | ![Inkwash diagram of the spheres of motion for the Moon, Mercury, and Venus around the Earth. “Della fabrica del mondo,” [1643], leaf 51r.](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/7c979a08-574f-4fed-865f-f4dff99425c4/Della%20fabrica%20del%20mondo.png) Inkwash diagram of the spheres of motion for the Moon, Mercury, and Venus around the Earth. “Della fabrica del mondo,” [1643], leaf 51r. |

Galileo Galilei died in 1642. His embrace of heliocentrism had been deemed heretical by the Catholic Church, and consequently, the Church had placed his 1632 book Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems) on the Roman Index, a list of books banned for lay Roman Catholic readership. Despite this censorship, models placing the Sun at the center of the universe did not disappear from Italian or European astronomy, and students and scholars alike continued their exploration of heliocentrism. A manuscript recently acquired by the Linda Hall provides a window into how an Italian tutor and student learned about astronomy in the immediate post-Galilean period.

“Della fabrica del mondo ouero cosmografia” (Of the fabric of the world, or cosmography), was written as a structured dialogue between a student and a Jesuit tutor, a common teaching tool in early modern Europe. The manuscript features two interlocutors: Pellegrino Cantelli (Pell.), the tutor, and Girolamo Calcagni (Gir.), the student. Throughout this work, Cantelli asks questions and Calcagni answers. The text, divided into three sections, discusses the Earth and the solar system, celestial bodies, and practical astronomy, including astrology. The Library’s neatly-written copy includes 29 pages of celestial tables, as well as ink and inkwash diagrams of planetary motion, world systems, and stellar phenomena. The Thomas Fisher Rare Library at the University of Toronto holds the only other know copy of this manuscript.

Dario Tessicini, a University of Genova scholar who studied the Fisher copy of “Della fabrica del mondo,” found information about both men in Italian archives. According to his research, Cantelli was a member of the Jesuit order and studied in Bologna or Parma in 1636. When the manuscript was written, he was about 30 years old. Girolamo Calcagni, the student, was a member of the wealthy Calcagni family of Reggio Emilia, near Bologna and Parma. At the time the manuscript was written, Calcagni was about 18 years old. These sparse facts give us a sketch of the manuscript’s creation: the older Cantelli was called to instruct the younger Calcagni in astronomy, and this manuscript attests to what they learned. Although the manuscript is an original work, large sections of the text are borrowed from other sources. Such paraphrasing may violate modern standards of academic integrity; however, this manuscript was intended for private study.

Diagram of the Tychonic system from Giuseppe Biancani, Sphaera mundi, seu Cosmographia, 1620, p. 56

Tessicini identified Giuseppe Biancani’s Sphaera mundi, seu Cosmographia, published in 1620, as a major source of the “Della fabrica” manuscript. Biancani was an Italian Jesuit and astronomer who advanced new ideas about the structure of the world system and referenced the work of Tycho, Kepler, Galileo, and others. Many of the diagrams in “Della fabrica” are directly copied from Sphaera, complete with aligning lettering.

Tessicini also identified several passages in the manuscript that paraphrase works by Galileo, including Sidereus nuncius and Il saggiatore. Cantelli references Galileo by name and cites the total number and locations of stars within the Orion and Praesepe clusters (illustrated in Sidereus). Further, Cantelli describes such clusters as “an aggregate of very small stars, almost innumerable,” paraphrasing Galileo’s Il saggiatore. The close resemblance of the language suggests that they had direct access to copies of Galileo’s works and consulted them in drafting “Della fabrica del mondo.”

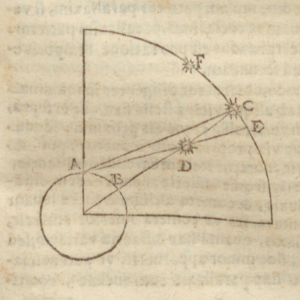

Comet parallax determination as illustrated in Sphaera mundi, 1620, p. 297. | The second section of the manuscript concerns celestial bodies, including a notable portion on comets. Debates over comets and comet parallax were the core of several highly public conflicts, including one between Galileo and the Jesuit astronomer Orazio Grassi between 1618 to 1623. Within the manuscript’s dialogue, Cantelli and Girolamo highlight the controversy surrounding the origin, formation, and nature of comets, as well as the methods for measuring comet parallax. In a key subsection, a diagram from Biancani‘s Sphaera is replicated to illustrate the concept of comet parallax. While the dialogue does not explicitly refer to the dispute between Galileo and Grassi, it does paraphrase extensively from Galileo’s Discorso delle comete. |

The manuscript dialogue argues that comets are celestial objects that emerge from the “milky circle” of the sky, which “gives creation to the generation of stars and comets,” rather than objects present since the beginning of the universe. While the distinction between changing and unchanging celestial objects may seem nonsensical today—as we understand better the long arc of cosmological time—the question of celestial bodies’ malleability was key to the debate over classical cosmology. The Aristotelian or classical model, with the Earth at the center of the universe, posited that all non-Earth celestial bodies were smooth, perfect, and unchanging. Cantelli’s arguments against the Aristotelian doctrine are so strong that Calcagni deems the classical model insufficient within the dialogue and asks Cantelli to outright reject that world system.

This structured dialogue provides a fascinating window into the discussion of astronomy and world systems between a scholar and his student. Calcagni and Cantelli present and discuss new ideas cautiously within the manuscript. This dialogue format is an effective tool: it allows questions to be posed, arguments to be declared unclear or insufficient to support, and controversial theories to be indirectly referenced. Also, it is apparent that Cantelli and Calcagni continued their scholarly work after the initial completion of their manuscript. An addendum on one of the blank back pages, dated 20 February 1643, highlighted two noteworthy texts for additional reading: Regiomontanus’ observations on the great comet of 1472, and Girolamo Sirtori’s Telescopium of 1618, the first book published on telescopes.

New ideas in the history of science do not disseminate themselves; books and people spread them. In Galileo’s wake, astronomers across Europe continued to question the nature of the solar system and the universe. Their wrestling with inherited models and new observations shaped the fabric of our world. By preserving and studying manuscripts like “Della fabrica,” we can learn how ideas spread and minds changed in early modern Europe and today. Researchers can now study this manuscript’s content, structure, and history in tandem with the works it draws heavily from in the Library’s History of Science Reading Room. Like Cantelli and Calcagni, scholars can continue their study of early modern astronomy with the Library’s copy of Sirtori’s Telescopium, one of three copies of Galileo’s Sidereus nuncius, and other books on the Roman Index.