Scientist of the Day - Zeno of Elea

Zeno of Elea, a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, flourished about 450 B.C.E; we estimate he was born around 490 B.C.E. and died around 420. Elea was a Greek colony in southern Italy, on the west coast, below modern Naples, not too far from where the Pythagoreans had set up their own colony, in Croton. Elea emerged on the map of pre-Socratic philosophy when Parmenides of Elea, around 475, wrote a book with the title: On Nature. In it, Parmenides argued that change is an illusion; that there is only one thing in the world, Being, and Being, logically, cannot change. That created quite a problem for natural philosophers, such as Heraclitus of Ephesus, who focused their attention on the nature of change. We wrote a post on Parmenides several months ago, and one on Heraclitus before that.

Zeno was a junior disciple of Parmenides, part of what is called the Eleatic School, and he took it upon himself to provide further evidence for the illusory nature of change, by proposing a series of paradoxes, now known as Zeno's Paradoxes. There seem to have been nine of them; four of which were discussed in detail by later writers such as Plato and Aristotle. We will present just two of them here, which will be enough for you to get the idea.

The most famous Paradox of Zeno is that called Achilles and the Tortoise. Consider that Achilles is going to race a tortoise, and the tortoise, reasonably, has been given a head start. One can break the race down into stages, says Zeno. In the first stage, Achilles runs up to where the tortoise was at the start of the race, say point A. But the tortoise will, in the meantime, have advanced a little, to point B. In the second stage, Achilles races to point B. Meanwhile, the tortoise advances a little further to point C. In the third stage, Achilles runs to point C, and the Tortoise ambles to point D. And so it goes. Zeno has broken the race down into an infinite number of stages, and Achilles could never go through infinite segments in a finite time. Ergo, Achilles cannot catch the tortoise. The fact that, if we staged such a race, we could observe Achilles passing the tortoise in very little time, just deepens the paradox.

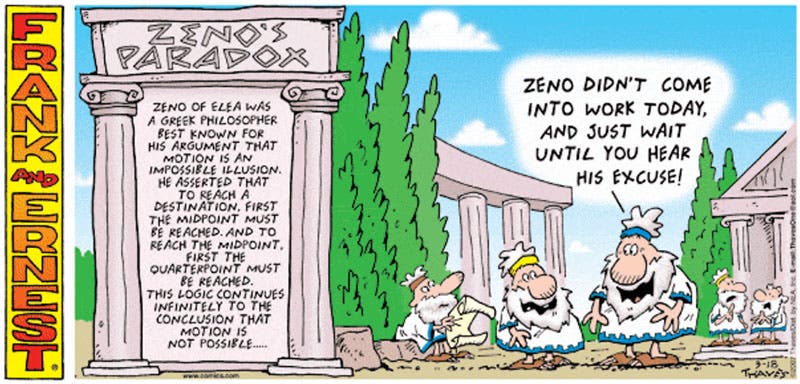

A second paradox, which is even more confounding, is sometimes called the Dichotomy Paradox, which is puffery – it should just be called the Stay-at-Home Paradox. Here Zeno points out that if you want to run from point A to point B, you first must reach a halfway point, C. But before you can get to C, you must arrive at point D, which is halfway to C. And before you get to D, you will have to reach point E, halfway to D. And so it goes, ad infinitum. You can, in fact, never leave A, or so the paradox demonstrates. The Stay-at-Home Paradox inspired a clever cartoon from Frank and Ernest in 2007 (second image).

The point of Zeno’s Paradoxes was to support Parmenides – to demonstrate that change is an illusion, or at least something we do not understand. In an era when no one realized that you could pass an infinite number of points in a finite time, Zeno's Paradoxes were a problem. Aristotle attempted to deal with them in his Physics, but his arguments were not satisfactory - how could they be? The paradoxes are still hard to handle. The main effect of Parmenides’ and Zeno's denial of change was to suggest to succeeding natural philosophers that perhaps there is more than one fundamental substance. The Ionian monists, like Thales of Miletus, had assumed that everything in the world derived from one fundamental substance, and Parmenides had taken that premise and shown that if there ever was just one thing in the world, then it must be Being, and there would be nothing left to change it into something else. One might bypass Parmenides and Zeno by proposing that there were several fundamental entities, perhaps four elements or qualities (Empedocles), or an infinite number of seeds (Anaxagoras), or atoms moving in a void (Democritus). And that is just what would happen.

We don't know much about Zeno, except for the paradoxes. We have no portrait from antiquity – not even a suspicious one – and the only early modern image (first image) is a doubtful one that was included in a 17th-edition of Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, which is one of the few ancient sources that talks about Parmenides and Zeno (but from the 3rd century C.E.!). Diogenes also tells us that Zeno died violently after being involved in a conspiracy against an Eleatic tyrant. Zeno made an appearance in one of Plato's dialogues, Parmenides, where he has a speaking role. Since he is described in the dialogue as being 40 years old, and Socrates is said to very young, Zeno’s birth-year has been estimated at 490 B.C.E., even though we have no reason not to believe that Plato was just making up the whole thing for the purpose of argument.

In future posts, we will take up the responses of Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and Democritus, to the problems raised by Zeno and the Eleatics, in the Era of the Pluralists.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.