Scientist of the Day - William Thomson, Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, a British physicist, was born June 26, 1824. Thomson was one of the pioneers in the new field of thermodynamics in the late 1840s, helped formulate the second law of thermodynamics in the 1850s (the one that says entropy is always increasing, so the universe is moving toward disorder), and was the technical genius behind the success of the transatlantic cable enterprise of 1865-66. For the latter effort, he was knighted in 1866, and in 1892, he was made a peer of the realm and ennobled as Baron Lord Kelvin, the name by which he is best known today.

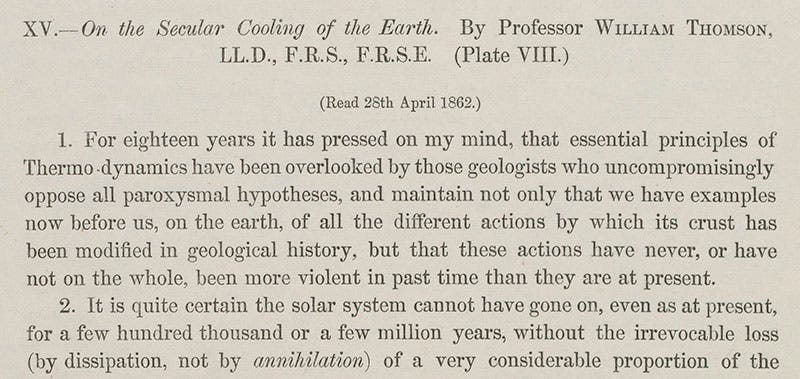

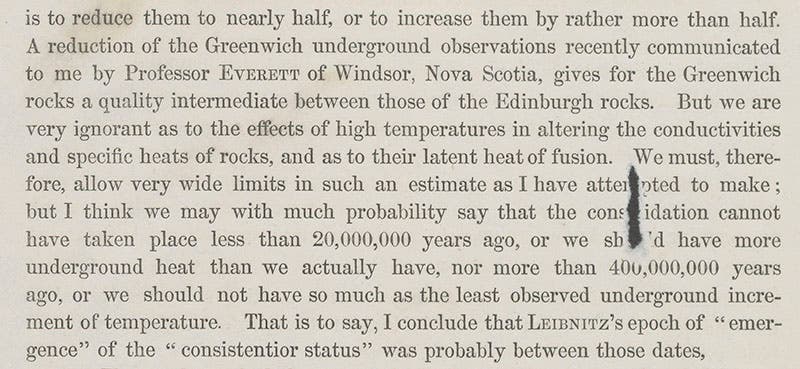

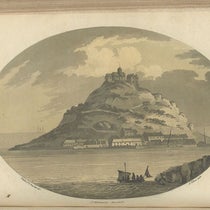

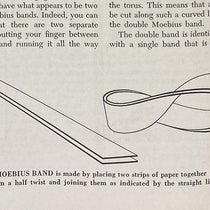

Thomson was an excellent physicist, but his greatest impact on late-Victorian science might have been a miscalculated date, which, although really not Kelvin’s fault, greatly hindered geology and evolutionary studies for about forty years. In 1862, Thomson determined the age of the Earth. Geologists and zoologists, such as Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin, had blithely assumed that the Earth was hundreds of millions, if not billions, of years old. Thomson was bothered by the fact that that these geological ages were the results of estimates of rates of erosion or sedimentation that were quite imprecise, so he set out to provide a more reliable date. He measured the temperature gradient within the Earth (how the earth’s temperature increased as one went down in a mine). He measured the energy that the Earth receives from the sun and the energy the Earth radiates away, and he succeeded in determining the rate of cooling. With all this data in hand, it was easy to calculate that 100 million years ago, the Earth was molten and uninhabitable, and that everything now on the Earth, from life to rocks, must be younger than 100 million years. Actually, he allowed for a wide margin of error, concluding that the Earth was possibly as old as 400 million years, or possibly as young as 20 million years, but the 100-million-year figure is the one that stuck. Thomson published several papers with his results; we show the one read to the Royal Society of Edinburgh (third image) and the page with the results of his calculations of the age of the Earth (fourth image).

Darwin for one was appalled at the young age for the Earth that Kelvin provided him, but did not feel he could just flat-out reject it, for this was a respected physicist talking. So he tried to come to terms with a relatively young Earth, looking for ways to speed up the rate of evolution, and deviating from his original idea that natural selection was the primary source of evolutionary change.

As it turns out, Thomson’s date was wrong. Thomson had assumed that the Earth has no internal heat source, so that it cannot replace heat lost by surface radiation, and thus must be cooling off. Thomson was unaware, as was everyone at the time, that the Earth is heated internally by radioactivity, and thus is not cooling off, at least not at the rate that he measured. It was Ernest Rutherford who, after radioactivity was discovered in 1896, applied knowledge of this new phenomena to theEearth and determined in 1903 that the Earth’s age could not be determined by measuring cooling rates, and that the Earth could be, and probably was, billions of years old. Thomson, interestingly, was still alive at the time of Rutherford’s announcement, but, not surprisingly, the eighty-year old physicist refused to admit that his age for the Earth was fatally flawed by an erroneous assumption, and it was not until after Kelvin’s death in 1907 that it was realized that the rate of radioactive decay of uranium could provide a new way of dating the Earth, yielding dates on the order of several billion years. By 1913, the tyrannical reign of the 100-million-year-old Earth was over.

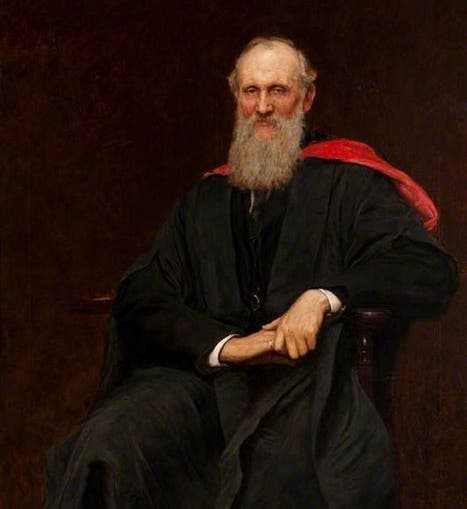

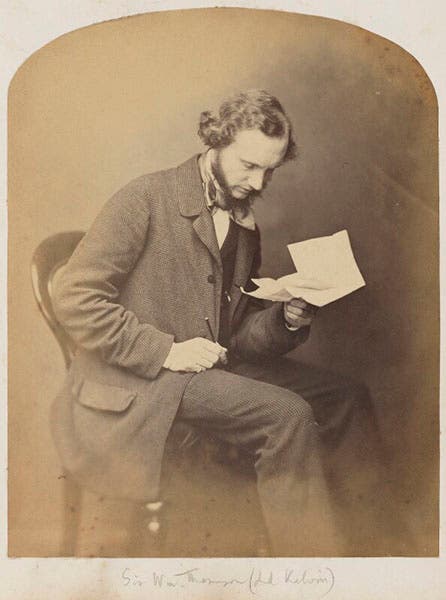

Because he was such a powerful force in science for so long (he was professor at Glasgow for over 50 years), one portrait will not do, so we show you a photograph taken in the late 1850s, just before he made his age-of-the-earth calculations (second image), and a painted portrait made in the 1890s, when Kelvin was probably the most famous physicist in the world (first image). There is a beautiful memorial for Kelvin at the University of Glasgow (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.