Scientist of the Day - William Rutter Dawes

William Rutter Dawes, an English amateur astronomer, died Feb. 15, 1868, at the age of 68. His father was a schoolteacher. Young Dawes obtained a small refracting telescope and became quite interested in observing the stars, especially double stars, and he went all the way through the list of double stars that William Heschel had compiled back in the 1780s. Dawes chose medicine as a profession, training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, and then switched to the ministry, acquiring a small parish in Ormskirk, north of Liverpool, where he upped his game by purchasing a larger refractor equipped with a filar micrometer, which allowed him to measure more accurately the separation of double stars.

However, his first wife died, his health deteriorated, and he had to quit his parish. In 1839, needing an income, he became the resident astronomer at George Bishop’s Observatory in Regents Park in London. Bishop, another amateur, a wealthy one, but with no observing skills himself, provided the instruments, and hired more skilled observers like Dawes to do the observing (John Russell Hind was another of Bishop’s hires). Here Dawes continued his study of double stars. Dawes was reputed to have the finest observing eyes in England, and his observations were exceptionally good and are still used today by double-star observers.

Dawes remarried, this time to a widow of means, which allowed him to move to Cranbrook in Kent, near the home of John Herschel, who had somehow become an informal patron of Dawes. There are some 75 letters from Dawes to Herschel still preserved at the Royal Society of London, and available online.

At some point, Dawes turned his attention from double stars to the planets. He independently discovered the crepe (innermost) ring of Saturn in 1850, just shortly after William Cranch Bond had seen it with the mammoth (for the time) 15-inch refractor at Harvard College. Observing planetary surfaces requires a larger telescope than one needs for double stars, and Dawes happened to learn that a fellow across the pond in Cambridge, Mass., was making large refractor lenses of exceptional quality. Dawes invited Alvan Clark to visit England, and Clark did so in 1859, bringing with him two lenses, one of 8-inch diameter, the other 8¼ inches. Dawes bought them both, told all his astronomical friends about Clark’s work, and Clark’s career was off and soon soaring. You can read more about that in our post on Clark.

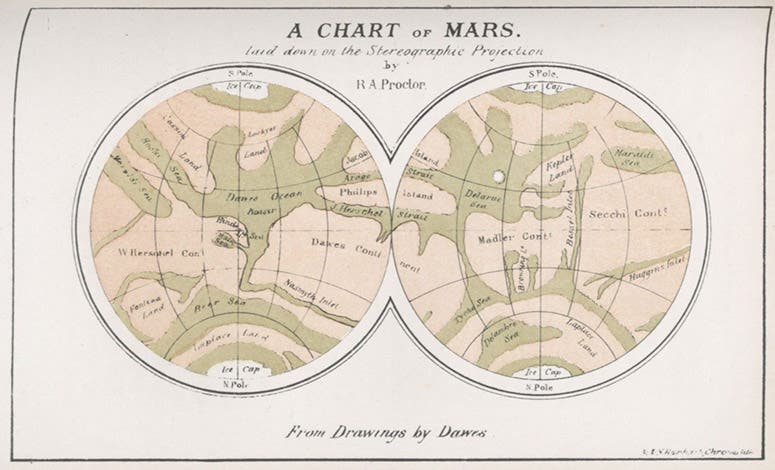

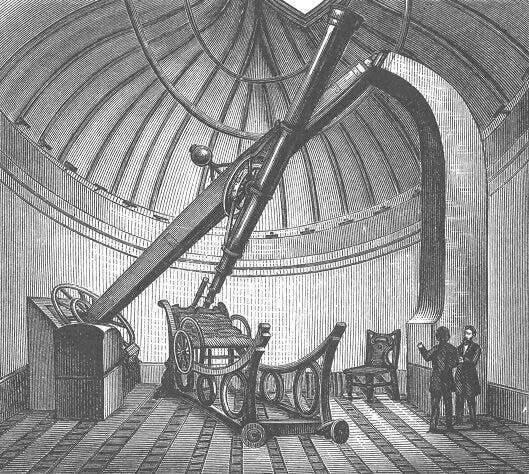

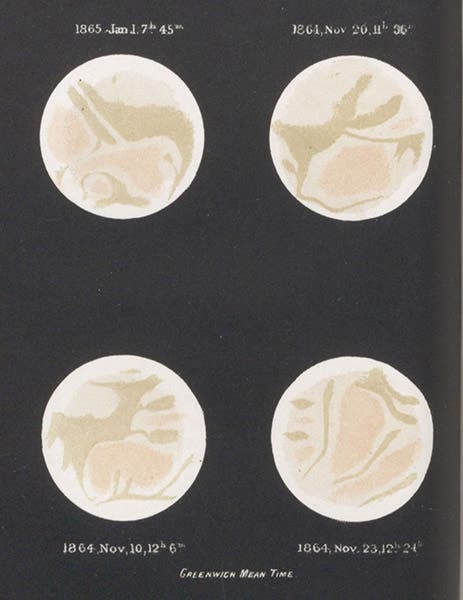

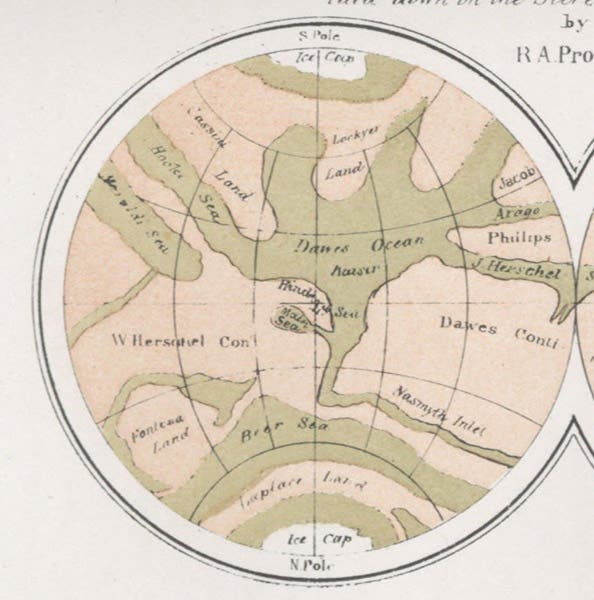

Dawes had the 8¼-inch Clark lens mounted (he sold the 8-inch one) and acquired another of 8¼ inch aperture from the English telescope maker, Thomas Cooke, and with those he zoomed in on Mars in the early 1860s. Mars is the hardest planet to view, even though it is often the closest one, because of its small size and dusty atmosphere. Dawes’ drawings of the Martian surface were some of the finest available, and Richard Proctor reproduced some of them in his book, Other Worlds than Ours (1870), along with a map of Mars he had compiled in 1867, based on those drawings, in which he named two features after Dawes. We do not have the first edition of Proctor’s book, but we have a fine copy of the 1882 edition, from which we show a plate of Dawes’ drawings (fourth image), as well as the map based on those drawings, where you can see the “Dawes Continent” and the “Dawes Ocean” (first and fifth images). You may view several more details of these in our post on Proctor.

One little known fact about Dawes is that he was at least partially responsible for turning the wealthy amateur William Huggins into a semi-professional astronomer. Huggins was a dabbler until he met Dawes at a BAAS meeting in Leeds in 1859, and Dawes, 25 years older, showed the younger Huggins how he could do astronomical work as an amateur that would make a real contribution to the profession. Huggins did exactly that. It may have helped that Dawes told Huggins about Alvan Clark and the value of fine lenses, and sold him the 8-inch lens that he had bought from Clark, which Huggins had mounted by Cooke and which he used regularly.

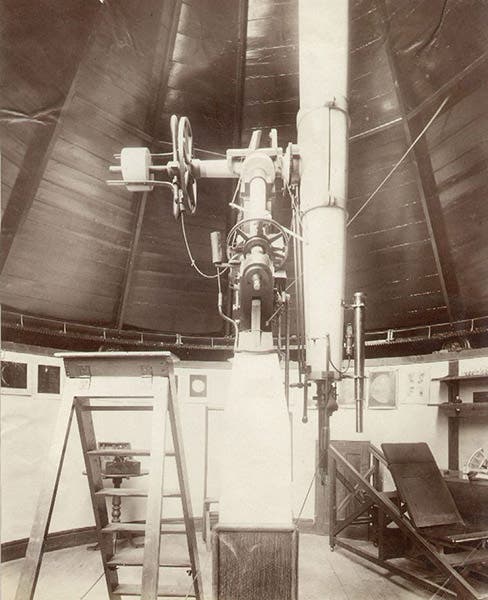

At least two of Dawes’ telescopes survive today. The Clark instrument is at Temple Observatory at Rugby School and apparently still in use (sixth image). The Cooke refractor ended up at Cambridge University, where it was renamed the Thorrowgood telescope and housed in a tiny building with a cone-shaped roof, and it is also still in use.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.