Scientist of the Day - William Molyneux

William Molyneux, an Irish natural and political philosopher, was born Apr. 17, 1656, in Dublin. Molyneux came from a well-to-do Irish family, was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, studied law, and spent his life doing pretty much what he wanted to, which was reading natural philosophers such as René Descartes, Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle (Irish himself), and later, Isaac Newton and John Locke. Molyneux also served in various political posts; he was, for example, Surveyor General of Ireland for a time, and he represented Dublin in the Irish Parliament for six years. He followed the goings-on of the Royal Society of London (and would become a Fellow of that Society). Deciding that Ireland deserved a similar institution, he founded the Dublin Philosophical Society in 1683. The group had an up-and-down life in the 17th century, depending mostly on whether Molyneux was around; they never launched their own journal, as the Royal Society of London did, but many of its members, such as William Petty, and Molyneux, published papers in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. The group became inactive after Molyneux died, but was revived several times, and eventually morphed into the Royal Irish Academy.

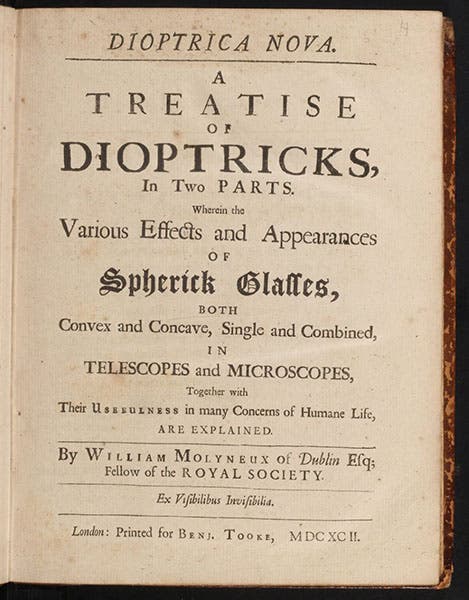

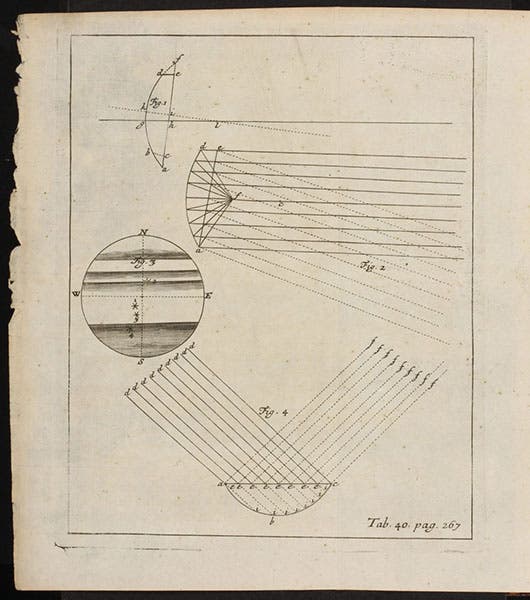

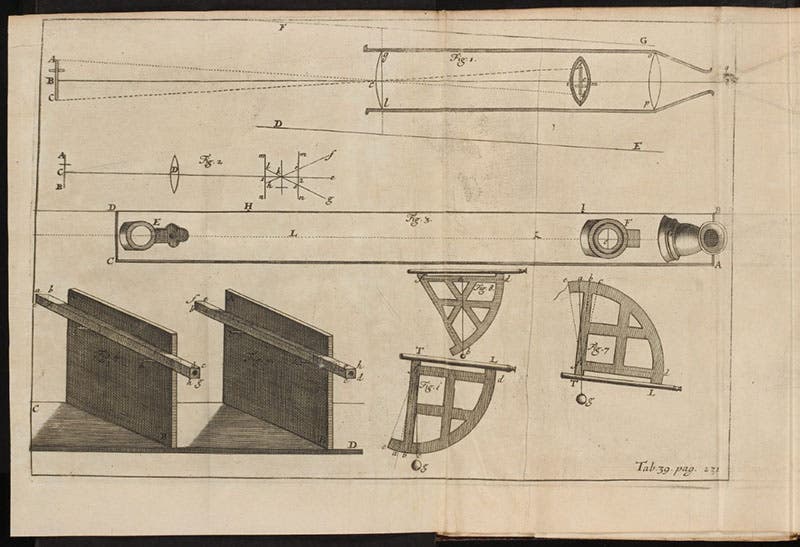

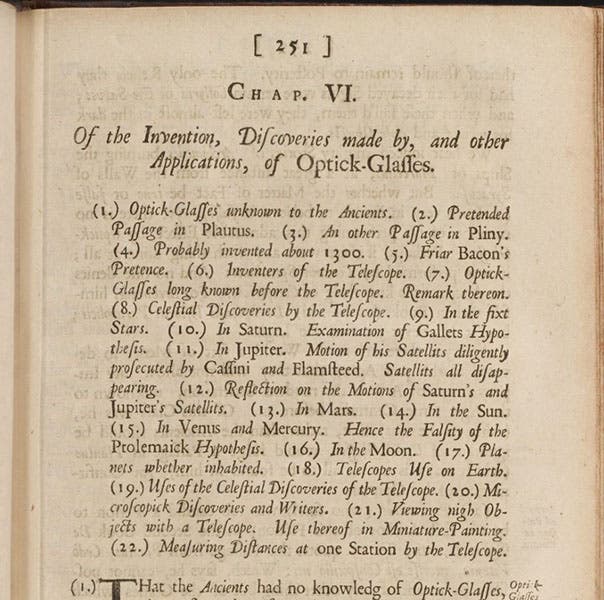

Molyneux's most important contribution to science was his Dioptrica nova, A treatise of dioptricks in two parts (1692), dioptrics being the study of the refraction of light by lenses, such as those in telescopes and microscopes. We have this work in our History of Science Collection, and it has been digitized. Molyneux made no major advancements in optics himself, but the book does have a long section on discoveries made with the telescope, such as the belts of Jupiter, which Molyneux figures in one of his infrequent engravings. Another plate shows how an image is formed, inverted, in a telescope. The Dioptrica nova was the first book on optics written in English – the works by Descartes, Johannes Kepler, and Christiaan Huygens were published in Latin. Perhaps the English Dioptrica nova inspired Newton to publish his own Opticks in English in 1704.

Molyneux is probably best known as the proposer of "Molyneux's problem," which John Locke addressed in his Essay concerning Human Understanding (1689), a book Molyneux greatly admired. Suppose, Molyneux asked Locke in a letter, a man is born blind and learns to distinguish a cube and a sphere by touch. If he were to suddenly regain his sight, would he be able to visually make the same distinction, and tell a cube from a sphere, before he was allowed to touch the objects? Locke was delighted with the question, since it clearly related to Locke’s contention that the mind at birth is a tabula rasa, a blank slate, and that we have no preconceived ideas. Locke concluded that the man would NOT be able to apply knowledge gained by the sense of touch to his brand new sense of vision, since that slate was still blank. It has been a frequently debated topic ever since.

One might be pardoned for thinking of Molyneux as a dilettante, but Locke, no mean thinker himself, was very impressed by Molyneux, and they maintained a strong friendship, through correspondence, from 1688 until Molyneux’s untimely death in 1698. Molyneux finally accepted repeated invitations from Locke to come visit; he travelled to London in 1698 and spent most of five weeks there in conversation with Locke. Locke was greatly distressed by Molyneux’s death several months later.

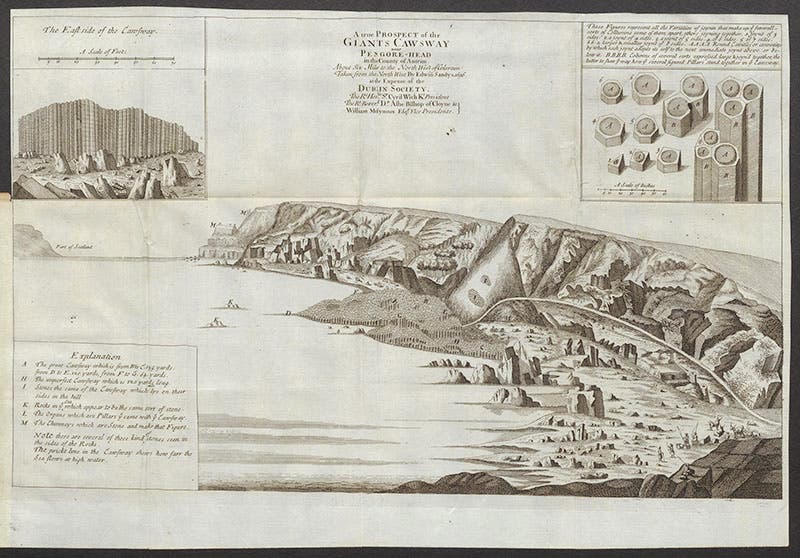

One of my favorite pieces by Molyneux is an engraving, devoid of printed text, that he sent to the Royal Society of London in 1697, depicting the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim, Ireland. The engraving was actually commissioned by William’s brother, Thomas, from an artist, Edwin Sandys. It was published without explanation in the Philosophical Transactions in 1697, except for a mention in the table of contents. The Giant’s Causeway had first been figured in print three years earlier in the same journal, but that was a crude drawing, and the engraving published by Molyneux was a great improvement. We show here the complete engraving (sixth image), and a detail of the primary prismatic basalt formation (seventh image). Ensuing discussion of the origin of the Causeway’s prismatic basalt would occupy geologists for the next century and a half, a topic that we pursued in our exhibition, Vulcan’s Forge and Fingal’s Cave (2004).

If this were a history of political economics blog, instead of a history of science series, we might feel called upon to mention a Molyneux treatise that was quite hackle-raising in certain quarters from the time it was published until the American Revolution almost one hundred years later. The treatise was called The Case of Ireland's being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (1698), and in it, Molyneux took the British Parliament to task for enacting statutes intended to control Ireland’s trade, especially the wool trade, which was seen as a great threat to England’s own wool industry. Molyneaux was not a separatist, but he did think that if the British Parliament was going to regulate Irish trade, then Ireland ought to have representation in Parliament. Locke, surprisingly, disapproved of Molyneux's treatise, although he did not let that get in the way of his friendship with Molyneaux. The Case of Ireland was thoroughly castigated elsewhere in England, but it never went away, especially when American colonists later had their own problems with taxation without representation.

Molyneux died on Oct. 11, 1698, just a few months after his stay with Locke. He was survived by his son Samuel, who inherited his father’s interest in optics and telescopes, and became the patron of James Bradley, the discoverer of the aberration of light We have written a post on Samuel Molyneux, as well as a post on Bradley.

The portrait of Molyneux (first image) is a bit of a puzzle. It was given to the National Portrait Gallery in London by a Molyneux heir, said to be by Godfrey Kneller, the famous portrait artist who painted Isaac Newton many times. Molyneux did sit for Kneller when he visited Locke in 1698, but that portrait never reached Molyneux and was supposedly lost. This appears to be a younger Molyneux, on which someone has recorded the date of is election to the Irish parliament. But it seems to be genuine.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.