Scientist of the Day - William Lassell

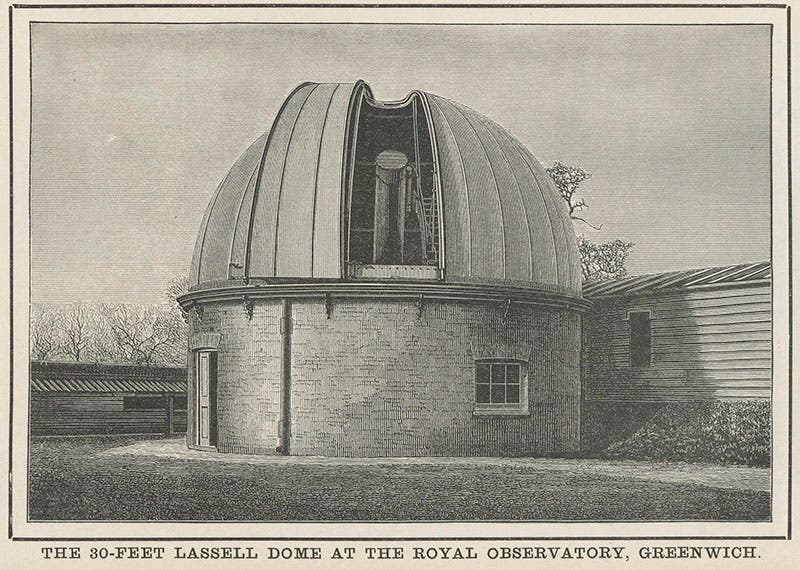

William Lassell, an English amateur astronomer and telescope maker, was born June 18, 1799. Lassell made a substantial fortune as a brewer of beer, which he sold to the thirsty factory workers of Liverpool, and then used his income to build several fine reflecting telescopes, with mirrors that he ground himself. Lassell was one of the first to use what we call an equatorial mount for his telescopes, where the main axis of the mount parallels the earth's axis. This means that if you rotate the telescope slowly around this axis, you can in effect make the earth stand still, and likewise the stars. Lassell first built a 24", 20-foot reflector (meaning the mirror was two feet across and the tube was 20 feet long). We have no image of that telescope in its original location, but much later it was given to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, where they mounted it in a dome, called the Lassell Dome, and we see a drawing of it made around 1890.

The 24”, 20-foot reflector built for William Lassell, in the later-built Lassell Dome of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, 1889 (Linda Hall Library)

With his 20-footer, Lassell discovered Triton, the large moon of Neptune, on Oct. 10, 1846. This was just 17 days after Neptune itself was discovered, and Triton is less than one-tenth the diameter of Neptune, which indicates just how good Lassell's telescope was. Using the same telescope, Lassell in 1851 discovered two new moons around Uranus, to go with the two that William Herschel had found shortly after he discovered Uranus in the first place. William’s son John Herschel named Lassell’s new moons, Ariel and Umbriel, after two sprites in Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock. No one knows why.

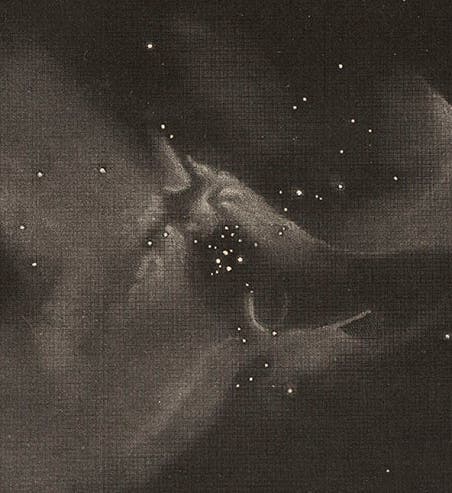

As Liverpool’s skies grew smoggier, Lassell moved his family and his telescope to Malta and resided there for a few years. While in Malta, he made detailed drawings of a number of deep-sky objects, including the Great Nebula in Orion. This drawing was engraved by James Basire III and published in the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1854. We show both the complete engraving (third image), which appears to be a mechanically-ruled mezzotint, and a detail of the heart of the nebula (first image).

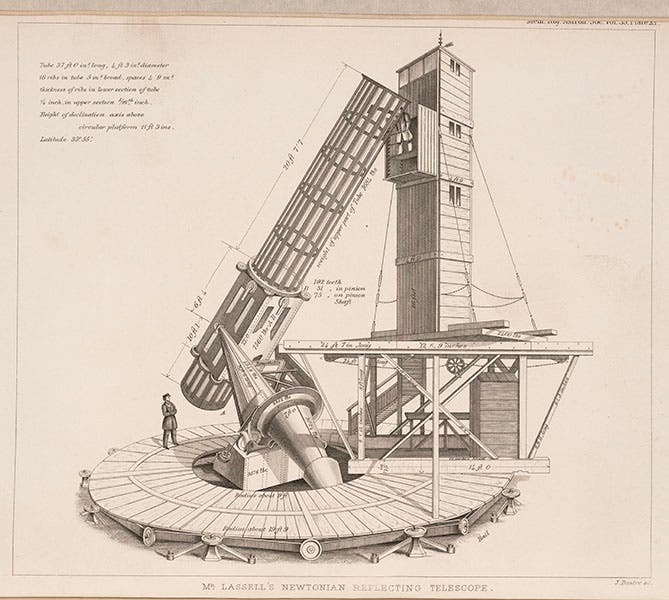

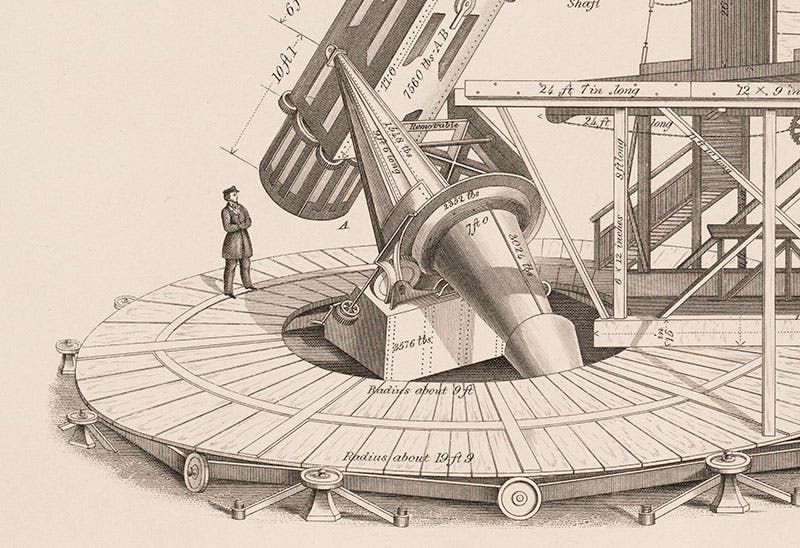

Lassell then moved back to a location outside of Liverpool. He proceeded to build a 48" reflector with a 37-foot open tube. When he found the seeing no better than before (surprise!), he moved back to Malta in 1861, bringing the 37-footer with him, and he remained there until 1865. We have a good image of this telescope, because Lassell drew it and published it in a later volume of the Memoirs (fourth image; for a detail, see fifth image). This is a Newtonian-style reflector, so the observer is at the top of the tower. You can see that the entire observing tower rotated around the telescope to accommodate changes in position of the tube. If you can read the legend at upper left, you will see that the latitude is given as 35º 55’, which tells us we are looking at the telescope as it was mounted in Malta. Lassell made more detailed drawings of deep-sky objects with his 37-foot reflector, but he published them as negatives, black drawings on a white background, and they are not nearly as dramatic as his Orion Nebula engraving, so we are not showing them here.

Lassel’s 37-foot reflector was the last of the great "speculum" reflectors, where the mirror was ground from a metal alloy called speculum, made mostly of copper and tin. All future large mirrors would be ground from glass, with a silver reflecting surface added as a thin film. Silvered-glass mirrors would be cheaper, lighter, brighter, and much less susceptible to tarnishing. Lassell was also the last of the great gentleman amateur astronomers, as astronomy became ever more professionalized in the late 19th century. The professionalization of any science is ultimately a good thing, but it is sad to lose the colorful and enterprising amateurs like Lassell who launched and maintained a science while waiting for the professionals to arrive.

There are a number of photographic portraits of Lassell; we show a carte-de-visite, made when he was in his sixties, in the National Portrait Gallery, London (sixth image). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.