Scientist of the Day - William John Bankes

William John Bankes, an English traveler and Egyptologist, was born Dec. 11, 1786. He came from a wealthy family with an estate in Dorset now known as Kingston Lacy, which William would later inherit. Bankes attended Trinity College, Cambridge, and became good friends with Lord Byron. He spent a few years in Parliament, following his father’s lead, and then set off on a European Grand Tour, which turned out instead to be a Middle East Grand Tour.

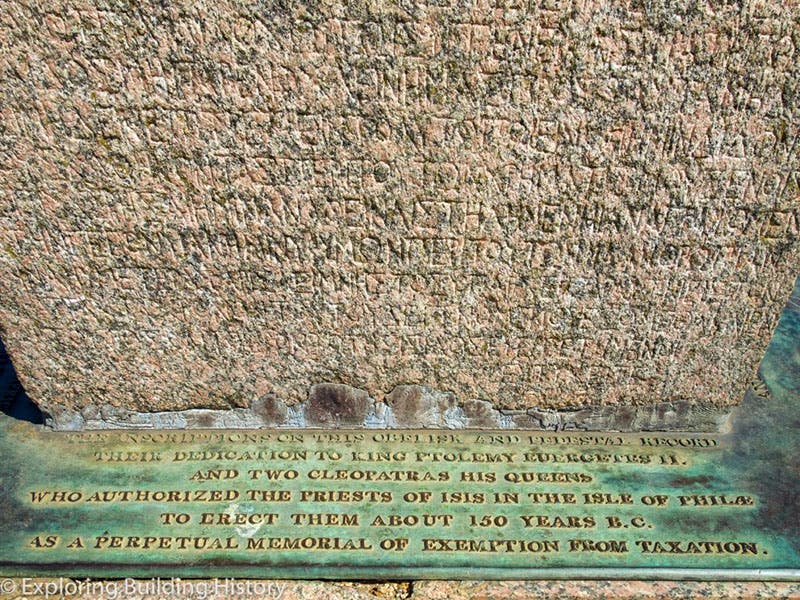

Bankes was in upper Egypt in 1815, at Philae, the site of modern-day Aswan, when he spied an obelisk, inscribed with hieroglyphics on all 4 sides, lying on the ground, and he thought it would be nice to have. The next year, the renowned antiquities-liberator Giovanni Belzoni claimed it for England and gave it to the English ambassador, Sir Henry Salt, who in turn handed it over to Bankes. Belzoni then agreed to transport the obelisk back to Bankes’ estate in England, which would turn out to be quite an extended ordeal. It took three years to get it to England, and two more to make it to Kingston Lacy, where it arrived in 1821. It would lie sprawled on the front lawn for many years, with the inscriptions slowly weathering away in the harsh climate (third image).

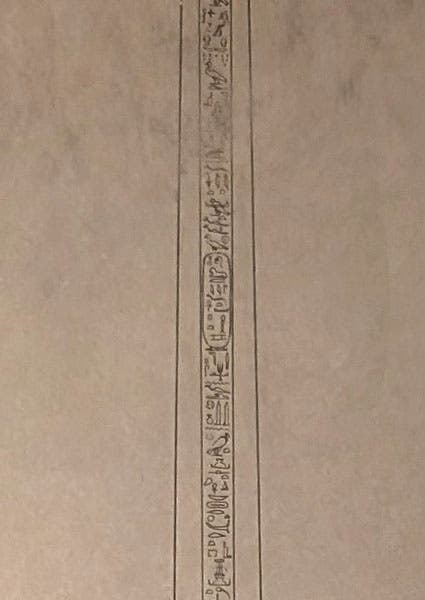

Bankes had spent the intervening time studying Egyptian inscriptions on site, in detail, making his own transcriptions and commissioning drawings from others, until he amassed quite a working library of manuscripts, all of which, I believe, are still there at Kingston Lacy. When the Philae obelisk finally arrived, along with its base, Bankes discovered that the base had an inscription in Greek, raising hopes that it was the same text as the hieroglyphic message on the obelisk itself (it turned out it was not, but it was close enough). Moreover, there were two cartouches on the obelisk (cartouches are cigar-shaped outlines with hieroglyphics inside, suspected to be the names of royalty), and there were two royal names in Greek on the base, Ptolemy and Cleopatra. You can see two of the cartouches on the Rosetta Stone at this entry in our exhibition catalog, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt (2006).

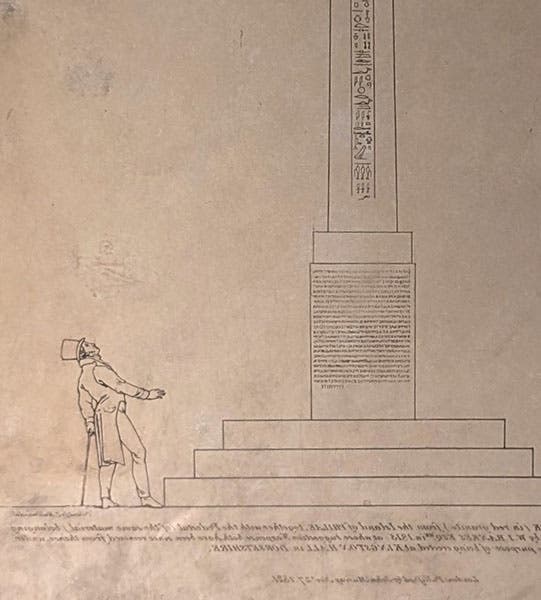

In 1821, hieroglyphics had not yet been deciphered, although Jean-François Champollion in France and Thomas Young in England were hard at it, using the Rosetta stone as a key, with its inscriptions in Greek, demotic, and hieroglyphic. Bankes commissioned George Scharf to make large lithographs of all four sides of his obelisk, and he sent prints to Young and to French officials, where further copies were passed along to Champollion. Champollion was able to match up the hieroglyphics in the cartouches on the Rosetta Stone and the Bankes obelisk with the Greek letters in the names Ptolemy and Cleopatra. And he also finally realized – his key insight – that many hieroglyphic symbols were phonetic, meaning they represent sounds, not things. The Philae obelisk was as responsible for this realization as the more famous Rosetta Sone.

The next year, 1822, Champollion announced that he had deciphered hieroglyphics. Bankes was not all that pleased, since he would have much preferred that the Englishman Young had succeeded first. The Bankes obelisk remained on the lawn for years at Kingston Lacy. It was finally erected in 1839, and you may see it there today (first image). Two years later, in 1841, Bankes was accused of a homosexual act and was forced to flee the country. If he ever saw his obelisk again, in the 14 years before his death, he did so on the sly, in disguise, and with lots of people sworn to secrecy. Many people, knowing Bankes, suspect he might have done just that.

I was looking though all the images of the Philae obelisk on Wikimedia commons – there are quite a few – when I saw two that were identified as showing lithographs made of the obelisk, oddly standing up against a wall. As I looked more closely – fortunately, these were large files – I saw these did not show prints, but the original lithographic stones from which the prints were made, just standing in some corner, with the text in reverse, as it should be on a printing stone. I include here not only one of the original dark photos, but two enlargements I made showing Bankes himself at the base (fifth image), and a cartouche for Cleopatra on the upper part of the obelisk (sixth image). Since Kingson Lacy is now part of the National Trust, I presume those lithographic stones are well known to those at the site, and to specialists. But I had never seen it mentioned that they survive.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bivouac on Jan. 26 [1854], chromolithograph from a sketch by Balduin Möllhausen, Explorations and Surveys for a Railroad Route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean: Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, by Amiel W. Whipple (Pacific Railroad Report, 3), 1856 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/55140a90-4b5d-4dac-832c-5def5cb51a10/Whipple1_cover.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)