Scientist of the Day - William Jacob Holland

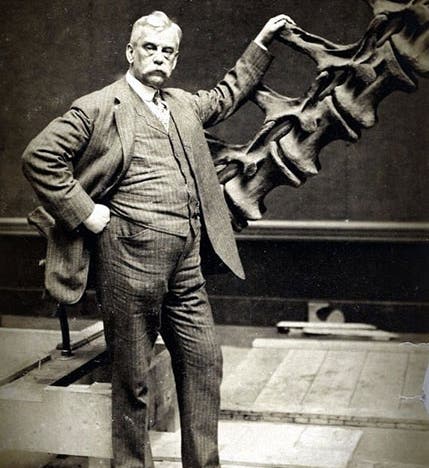

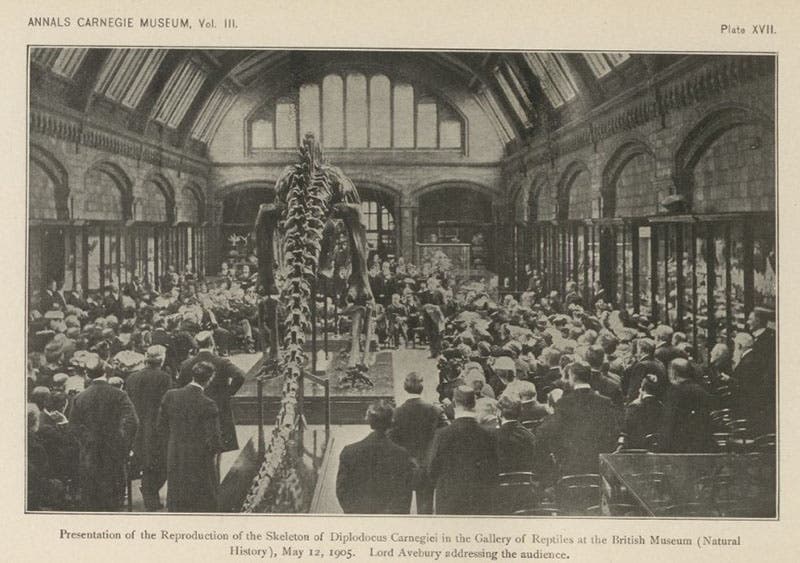

William Jacob Holland, an American naturalist and administrator, was born Aug. 16, 1848. Holland's scientific interest lay in butterflies, and he published an attractive book on the butterflies of North America in 1898 (which we have in the Library), but about that time he was invited to become Chancellor of what would become the University of Pittsburgh. Two years later, Andrew Carnegie snagged him for the directorship of the new Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. The Museum was founded in 1895; I am not sure if it had an official director before Holland, or whether Carnegie ran things. But in 1898, Carnegie was determined to secure a dinosaur for the Museum, and he sent Jacob Wortman out to Wyoming to investigate a lead that Carnegie had read about in a newspaper headline. That lead did not pan out, but another did, and soon Wortman had discovered a nearly complete skeleton of a sauropod called Diplodocus. Wortman however wanted to study early mammals, not dinosaurs, so he quit and went to the Peabody Museum at Yale, and Carnegie hired Holland, who then hired John Bell Hatcher to retrieve the Diplodocus skeleton. We focus on the Diplodocus skeleton, because it made the museum, and it made Holland. Hatcher wrote a monograph on the specimen, naming it Diplodocus carnegiei, and it would be restored and mounted and eventually installed in the Museum, when they had room for it (1907). Meanwhile, Carnegie decided to make plaster replicas of his Diplodocus and donate them to the leading natural history museums of the world. Holland was responsible for this, although Hatcher supervised the casting, and in 1905, the first plaster mount was presented to the British Museum (Natural History), in a lavish ceremony that Holland and Carnegie attended. The skeleton was promptly dubbed “Dippy.” Holland published an article about the affair later that year, with photographs of the presentation (second image, below), and of Dippy after the ceremony, without the crowds.

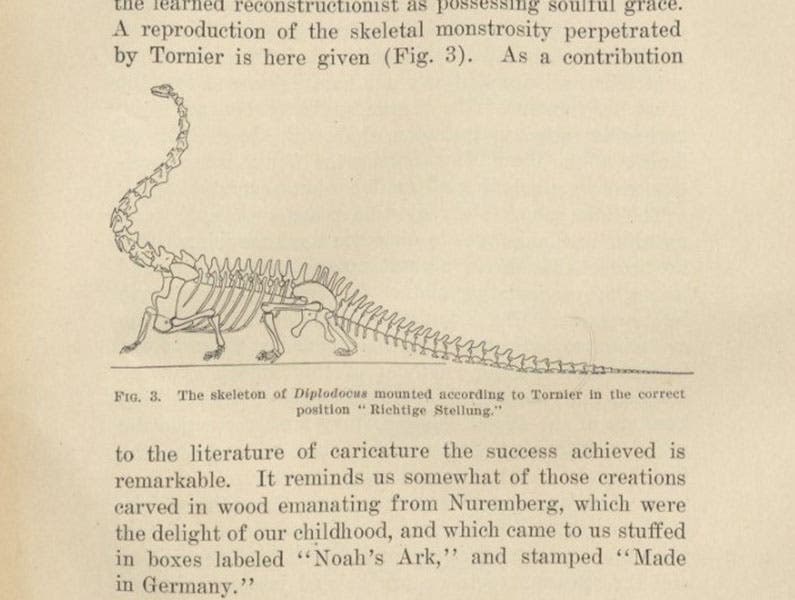

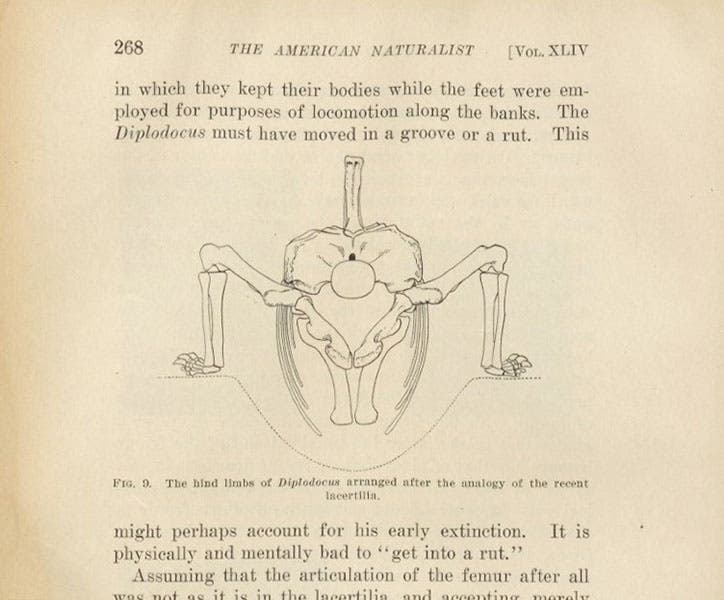

In 1909, Holland came to the defense of the Carnegie Diplodocus mount when a German naturalist claimed that the reconstruction was all wrong – that since dinosaurs were reptiles, they could hardly have stood upright like mammals, but must have sprawled like alligators; the author provided his own slinky restoration. Holland responded with an article in American Naturalist, in which he reproduced the German's reconstruction (third image, just below), and then pointed out that if Diplodocus had its legs sticking out from the sides, then its rib cage would have been below ground level, and it could only travel if Nature had thoughtfully provided grooves or ruts to accommodate its belly, a situation he illustrated with his own drawing (fourth image, below)

In 1909, the Carnegie Museum located a specimen of Apatosaurus (still often referred to as Brontosaurus) in a quarry in Utah, a skeleton of which had already been mounted in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. The New York Apatosaurus was missing a head, as was the original skeleton found by Othniel Charles Marsh and waiting to be mounted at Yale’s Peabody Museum. Marsh had married his skeleton with a skull found some miles away, a blunt, broad skull, and AMNH had followed suit. Holland, to his credit, was suspicious about the skull in place, and suggested that a narrow, Diplodocus-like skull was more appropriate. Both kinds of skulls had been found in the quarry that contained the Apatosaurus skeleton. Holland published an article in 1915 in which he pointed out that Marsh’s skull had been found miles away and there was no reason to think it belonged to Apatosaurus, and he leaned toward the Diplodocus-like skull. When the Carnegie specimen was eventually mounted in 1926, however, it had no skull at all, but displayed a conventional broad skull (which we now know belonged to Camarasaurus) separately, in front. After Holland’s death in 1935, a replica of the broad skull was placed on the skeleton. Had Holland had the courage of his convictions, and/or the support of his colleagues, the Carnegie Apatosaurus might have been the first such mount with the correct head. As it was, the museum world had to wait until 1976 for the heads to be swapped out at Yale, and then in the early 1980s at the Carnegie Museum.

A view of the Diplodocus and Apatosaurus mounts at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, photograph, 1936; the Apatosaurus (on the right) was originally displayed without a head, which was placed down front; after Holland’s death, before this photograph was taken, a replica of the head was installed on the mount. It turned out to be the wrong head. In Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, vol. 11, 1936 (Linda Hall Library)

Holland worked for years on a monograph on Apatosaurus, but he was unable to finish it before his death. It was completed and published by Charles W. Gilmore in 1936. We displayed it in our Paper Dinosaurs exhibition once upon a time, which you can see here, and where you can also see Holland’s 1905 paper on the presentation of Dippy to the British Museum, his 1910 paper criticizing the sprawling Diplodocus, as well as Marsh’s original Brontosaurus restoration of 1883, which inaugurated the century of the wrong head.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.