Scientist of the Day - William Hunter

William Hunter, a Scottish surgeon, anatomist, and collector of art and natural history objects, died Mar. 30, 1783, at the age of 64. Hunter studied in Glasgow then came to London, trained as a male mid-wife – not the most socially respectable occupation in Georgian England – and set up his own anatomy school, but he still managed to rise to the status of gentleman and make a great deal of money. He spent it on books and collectibles, and then left his eclectic museum and considerable library to Glasgow University, where the Hunterian Museum and the Hunterian Art Gallery still welcome visitors.

In his anatomy classes, Hunter began the tradition in England of allowing students to dissect their own cadavers (a teaching practice that was called, before Hunter, the “Paris tradition”). His reputation as an anatomy instructor was so great that he was appointed the first Professor of Anatomy at the recently founded Royal Academy of Arts in 1769. His most famous publication is the Anatomia uteri humani gravidi (1774), with many exquisite engravings of the human fetus in utero by Jan van Rymsdyk; this book, being out of scope, is not in our collections, but there is a copy at the nearby Clendening Library at the KU Med Center.

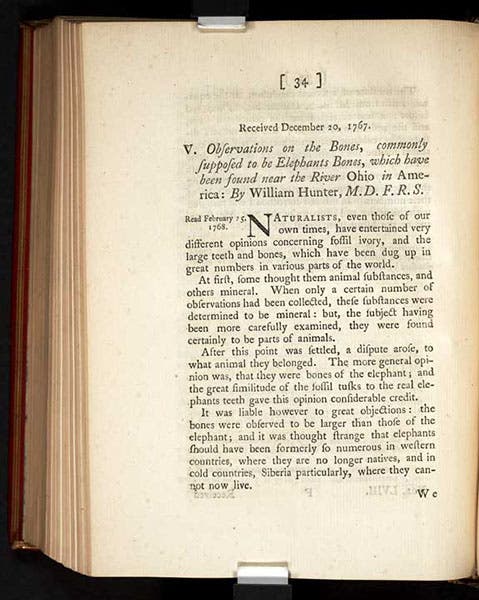

Among his natural artifacts, Hunter had a jawbone from Kentucky of an elephant-like animal (now known to be a mastodon), and he wrote a paper for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1768, arguing that the "American incognitum" must have been a terrifying beast, although it was now, thankfully, extinct.

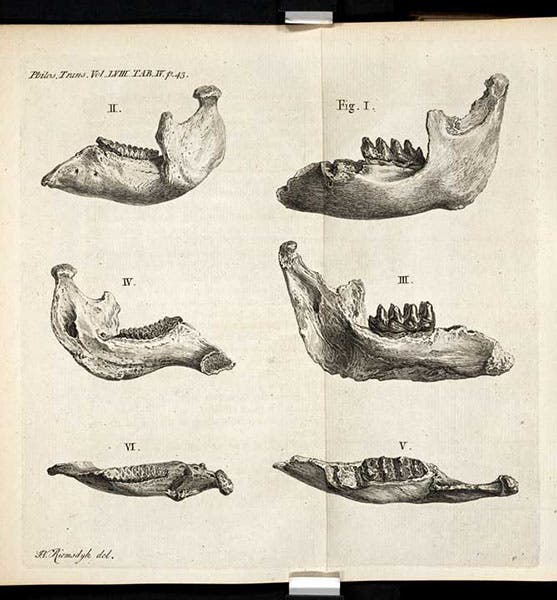

We show here the first page of that article, and the folding engraved plate, which compares three views of an elephant jaw, on the left, with Hunter’s mastodon jaw, on the right (second and third images).

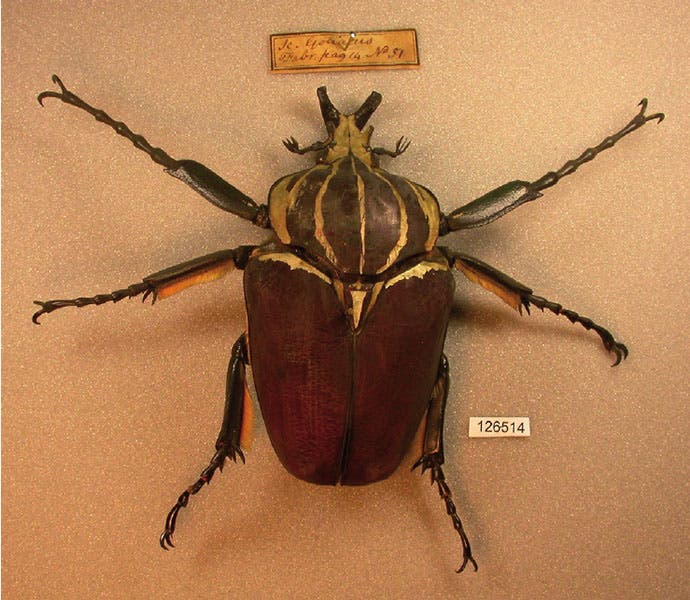

Hunter also acquired a very large beetle from a surgeon who found it floating at the mouth of the Gabon River in West Africa in 1766; this was the first know specimen, or the "type" specimen, of what we now call a Goliath beetle. It is still preserved in Glasgow (fourth image). Hunter’s goliath beetle inspired other English insect collectors to try to acquire their own, including Dru Drury, who sent Henry Smeathman to West Africa to find him one. We told part of the story in our post on Smeathman, but we need to write one on Drury, who got himself in very bad graces with Hunter by using a drawing of Hunter’s beetle without attribution.

Perhaps Hunter’s greatest find was rediscovering the anatomical manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci, which had lain unrecognized for many years in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Hunter identified them as Leonardo's in 1773 in a letter to Albrecht von Haller, in which he called Leonardo "the best Anatomist of his time”. Hunter hoped to publish the drawings, but that wish, alas, was cut short by his death.

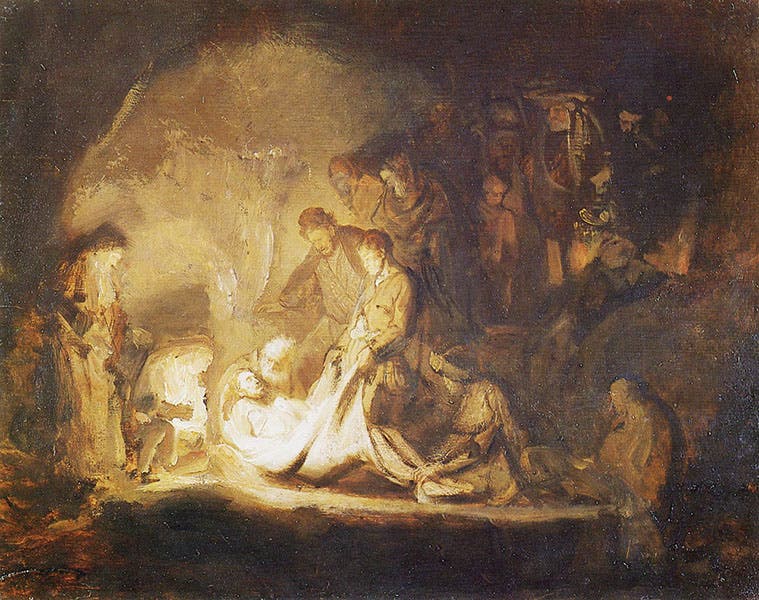

Finally, we should note that Hunter, in his guise as art collector, had a keen and discerning eye. In 1771, he bought an oil-sketch of the entombment of Christ, which he thought looked promising; he paid 12 guineas for it. It turned out, as Hunter perhaps knew, that the painting was by Rembrandt. It went to Glasgow along with everything else, and Rembrandt’s The Entombment is now one of the prize works of art in the Hunterian Art Gallery (fifth image).

The best-known portrait of William is at Glasgow University (first image). Less well known is Hunter’s appearance in a painting in the Royal Collection called The Academicians of the Royal Academy, 1772, by Johan Zoffany (sixth image). In this invented scene, William Hunter is just to the left of center, with his finger on his chin, dressed in red, and shorter than anyone else. That is Sir Joshua Reynolds right next to him, on the viewer’s left, dressed in black. A pen-and-watercolor copy of this painting was made in 1773 and is now in the National Portrait Gallery in London; not only is it more charming than the original, but it has buttons that allow you to identify all the standees, including Benjamin West. You may access it here.

William had a younger brother, John Hunter, who was also a surgeon, anatomist, and collector. The two had a falling out and William cut John out of his will, but John did quite well for himself and founded his own museum in London, and it is as full of marvels as William’s. It is part of the Royal College of Surgeons. So if you ask your travel agent to schedule a trip to the Hunterian Museum, be sure to specify which one, Glasgow or London, although you could hardly go wrong with either.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.