Scientist of the Day - William Pickering

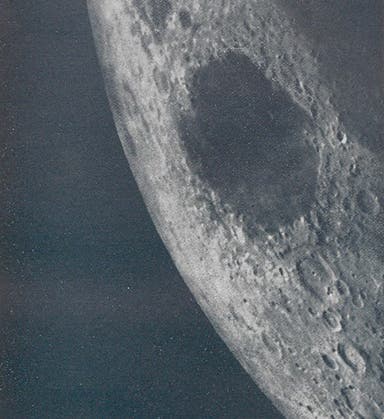

Mare Crisium, photograph taken in 1901 in Jamaica, in The Moon, by William H. Pickering, 1903 (Linda Hall Library)

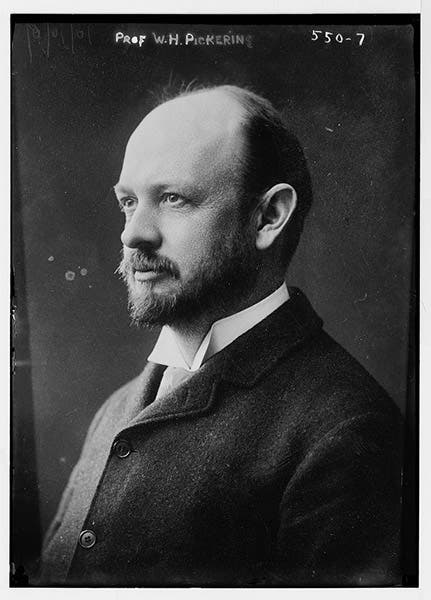

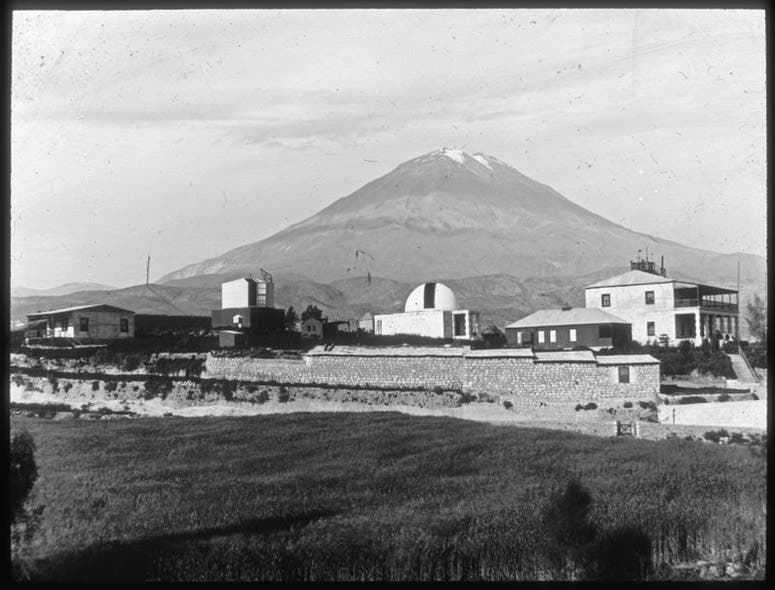

William Henry Pickering, an American astronomer, was born Feb. 15, 1858, in Boston. Pickering was the younger brother of Edward Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory for 42 years, beginning in 1877. William attended MIT and began teaching physics at Harvard in 1887. But his passion – in addition to mountain climbing – was the solar system – he liked observing the Moon, the planets, planetary moons, and eclipses of both Moon and Sun. He led an eclipse expedition to northern California in 1889 to observe the total solar eclipse of that year, and he and Edward collaborated with the New York Herald newspaper, which established a dedicated telegraph line from California with the sole purpose of conveying the latest information to their headquarters in New York City. Since Pickering became a minor newspaper celebrity as a result, Edward chose William in 1891 to set up a new southern high-altitude observatory at Arequipa, Peru, in order to compete with the newly opened Lick Observatory in the Sierras east of San Jose, California. The funds for such an observatory had been provided by the Boyden Fund, and the observatory would be called the Boyden Station.

Unfortunately, Pickering was a bit of a loose cannon and not at all prone to following the instructions of brother Edward, who wanted to keep expenses down at Arequipa, and who wanted William to concentrate on spectrographic and photometric work that could be analyzed back at Harvard. Instead, William built himself a lavish house and focused the observatory’s attention on visual observation of the coming opposition of Mars in 1892. He once again linked up with the New York Herald, which welcomed his telegraphed observations of Mars, at their expense, while Edward at Harvard could not afford telegraph fees and had to wait months between communications with William. Before long, Edward got fed up with William's antics and fired him. Thus ended William’s short tenure as director of Harvard College’s new southern observatory, although he stayed on at Harvard in other capacities.

After returning to the United States (Edward thoughtfully let William continue in Peru until the Mars opposition was over in mid-1892), William became friends with Percival Lowell, a wealthy amateur astronomer and one of the Boston Lowells, who also had a passion for Mars, and William helped Lowell build his own private observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, where the seeing was just as good as that in Arequipa. Lowell Observatory opened, with two borrowed telescopes, just in time for the Mars opposition of 1894, at which Lowell first observed the canals that would bring him to public attention. William, however, did not agree that many of the canals were doubled, or “geminated” (twinned), to use the term then popular, which would be certain evidence that they were not natural and had been constructed.

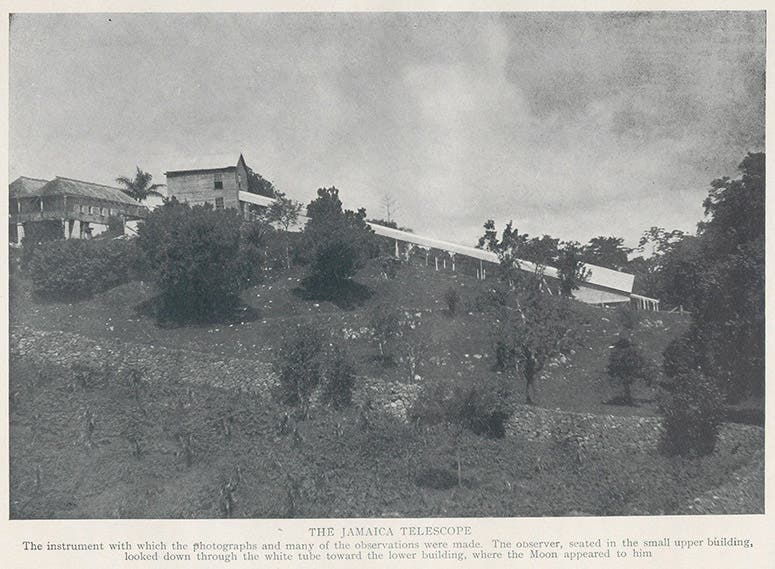

The 135-foot telescope in Jamaica, used by William H. Pickering to photograph the Moon in 1901, in The Moon, by William H. Pickering, 1903 (Linda Hall Library)

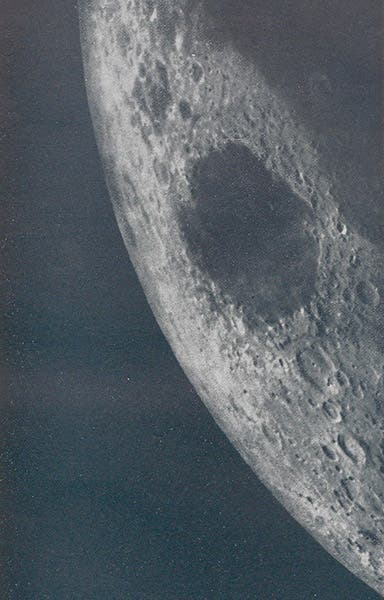

In 1899, William was sent by Edward to check out Jamaica as a possible site for another satellite observatory, and William reported that the seeing was just fine. In late 1900, William returned with a small crew to install an odd 135-foot refractor, that used an 18-inch mirror to reflect an image through a 12-inch objective and back up the long tube to an observing building (fourth image). It worked well, and William spent the year 1901 making a photographic record of the lunar surface, for the purpose of producing a lunar atlas. The lunar atlases published to date were far too expensive for an individual to own, and tended to be incomplete as well. Pickering wanted to publish an affordable photographic atlas, with all the photos at a uniform scale, showing the lunar surface under varying conditions of illumination. The result was The Moon : A Summary of the Existing Knowledge of our Satellite (1903), which was neither oversize nor flashy, but still attractive, easy to use, and within the budget of amateur lunar observers. It was the prototype for all subsequent observers' atlases. We displayed it, opened to plates depicting the region of Mare Nectaris, in our exhibition, The Face of the Moon. We show here two different plates, depicting the Mare Crisium (Sea of Crises), near the lunar limb (first image), and the Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains), with the dark floor of the crater Plato easily visible (fifth image).

Mare Imbrium and the dark floor of the crater Plato, photograph taken in 1901 in Jamaica, in The Moon, by William H. Pickering, 1903 (Linda Hall Library)

Pickering then turned his attention to the undiscovered planets of our solar system, of which he was convinced there were many. Lowell had predicted the existence of one such planet, which he called Planet X. But Lowell had nothing on Pickering, who predicted, between 1909 and 1932, the orbits and parameters of no fewer than seven mystery planets, which he called, in succession, Planets O, P, Q, R, S, T, and U. Since, unlike Lowell, he did not have a large telescope at his disposal, he pleaded with others to search for his planets, but only once, in 1919, was an extensive search made, in this case for Planet O (actually Pickering’s second Planet O), with no success. Lowell died in 1916, but when Pluto was discovered in 1930 at Lowell Observatory, it was claimed by Vesto Slipher, the successor to Lowell, that the discovery was made as a result of Lowell's prediction of Planet X. Pickering begged to differ; he quickly pointed out that his predictions for Planet O were closer to the actual Pluto than Lowell's predictions for Planet X. Moreover, it was learned, after re-examining the photographic plates from the 1919 search for Planet O, that Pluto had showed up 4 times on those plates, so if someone had recognized the newcomer, it would have been as a result of Pickering's predictions, not Lowell's. No one took that claim very seriously, and neither, really, did Pickering, who always gave full credit to the Lowell Observatory for the discovery of Pluto, even though he clearly thought his contributions were under-appreciated. After Pickering’s death in 1938, Annie Jump Cannon recounted a story about Pickering and Pluto. Pluto had been so named in part because its abbreviated planetary symbol, PL, consists of the initials of Percival Lowell. Pickering said he agreed with the name, and he especially liked the symbol, which must, he ventured, be short for "Pickering-Lowell."

In 1899, while examining plates taken at the Boyden Station in Peru, from the directorship of which he had been fired in 1891, Pickering discovered the 9th satellite of Saturn, which he named Phoebe. It was the first moon discovered photographically. It was visited by the Cassini spacecraft in 2004, and had its picture taken again, this time from a closer vantage point (sixth image).

Our William H. Pickering should not be confused with William H. Pickering, another astronomer, who directed the Jet Propulsion Laboratory from 1954 to 1976, and who also was fascinated with Mars, but who used spacecraft rather than telescopes to explore it.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.