Scientist of the Day - William Henry Hudson

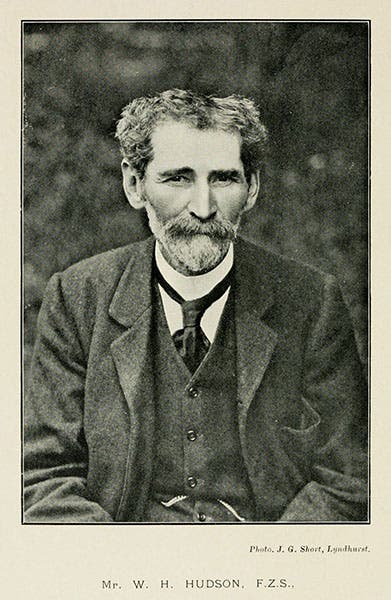

William Henry Hudson, an American/Argentinian/British naturalist and writer, was born Aug. 4, 1841, in Argentina, to American parents of British descent. His mother and father had moved to Patagonia to eke out a living; Hudson lived there until he was 33. He spent most of his time studying the wildlife, especially the birds, which he came to know intimately. He moved to England in 1874 and never went back to South America. He began writing in the 1880s. One of his early books was Argentine Ornithology (1888-89). He was never really happy with it, because some of the material in the book was not his own, and the book was not widely circulated. So thirty years later, he was happy to republish it, throwing out all the stuff that wasn't his, and adding 22 full-page color illustrations by the highly-regarded Henrik Grønvold. This two-volume work is one of several Hudson publications that we have in the Library, and we are going to make it the centerpiece of our discussion.

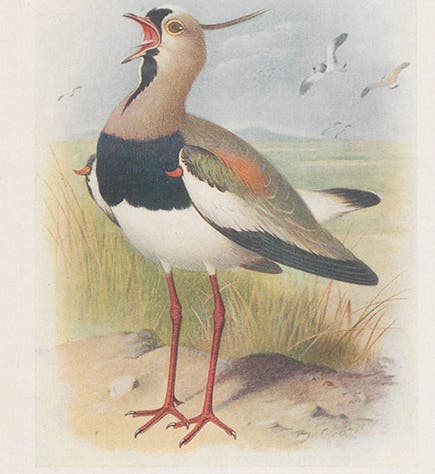

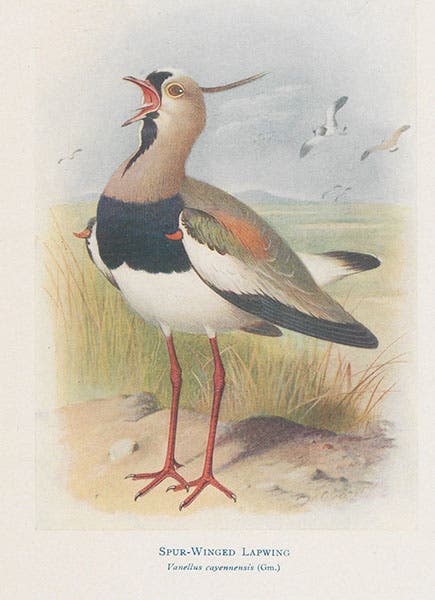

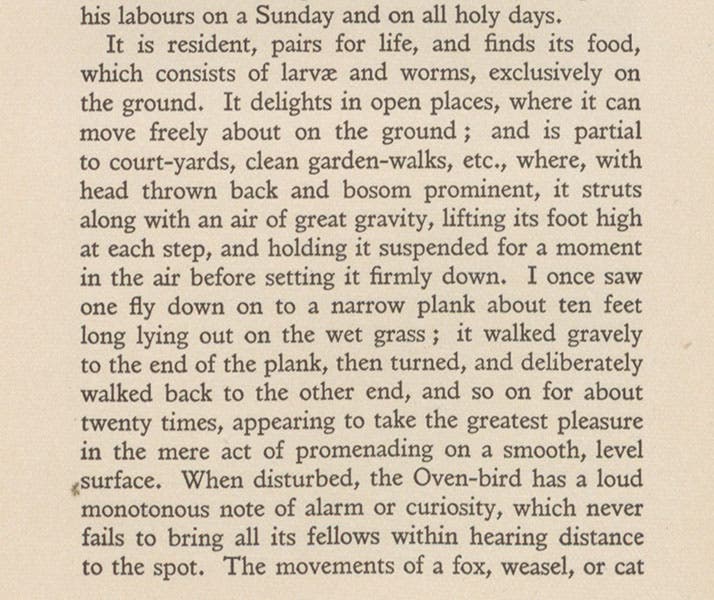

Usually, when we write about a bird book, we focus on the illustrations; indeed, we have included four of them here, because this an illustrated post. But the color plates are the least important feature of the book. Hudson was not an artist, nor was he a taxonomist. He was an observer, one of the best observers of birds there ever has been. He was also a keen listener, and it seems as though he could identify by ear not only every species he encountered, but many individual birds. In one delightful chapter, he recounted how he heard a beautiful but unfamiliar song coming from a thicket. The song stopped, and then he heard, coming from the same thicket, a Patagonian flycatcher, then a Diuca finch, followed by a scarlet tyrant-bird, a crested Tinamu, and a black-headed siskin. But when he heard several songs from birds that live only further north, he knew that he was being serenaded by just one bird, the white-banded mockingbird, Mimas the mimic, home from its winter travels (fifth image).

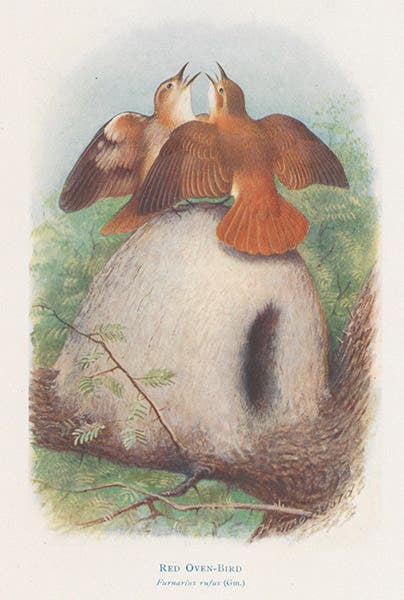

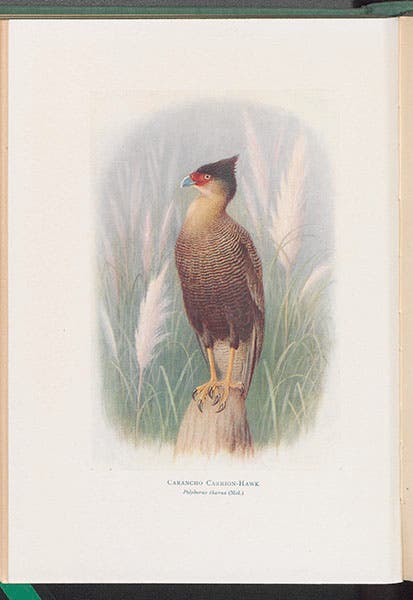

Hudson is such a joy to read because he treats birds as if they were family – which, for Hudson, I guess they were. I burst out laughing when he described the strutting of a red oven bird; it is such an amusing passage that I include it here (fourth image), and hope that it is readable. His description of the home-building of the oven-bird (third image) could only have been the result of watching dozens of pairs of oven-birds over the years fashioning their oven-houses from mud and bits of grass.

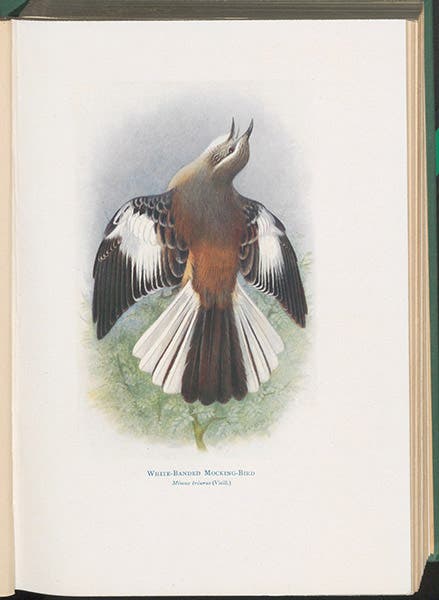

I first heard of Hudson when I read a book about the striated caracara, a bird found only in the Falkland Islands. The book, by Jonathan Meiburg, is called: A Most Remarkable Creature: The Hidden Life and Epic Journey of the World's Smartest Birds of Prey (2021). Not only is this a captivating book about a mind-boggling bird, but it provides a running account of the life and career of Hudson, who wrote about other carcaras (sixth image) in Birds of La Plata. Meiburg clearly admires Hudson above all other bird writers (and, to his credit, Meiburg writes nearly as well as Hudson). If you want to learn more about Hudson, or about the striated caracara, I highly recommend A Most Remarkable Creature.

Hudson wrote a lot of books – it was how he earned his living – of which the best-known might be a novel (his last novel), Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest (1904), which introduced a strange heroine, Rima the bird girl, who was the last of an unknown human-like species. The book is set in the jungles of the tropics, which Hudson never saw, and the book might well be a kind of wish fulfillment. The book was quite popular in the United States, and Hudson lived off his American Royalties until his death in 1922.

I don't think Hudson was a happy man, except when he was observing birds. His writings were publicly admired by all sorts of people, including Alfred Russel Wallace and Joseph Conrad. But even though he married, Hudson never really had anyone with whom he could share his love of birds. He had left Patagonia because he had found no kindred spirit there. And he never found a soulmate in England either. At the end of the introduction to Birds of La Plata, written two years before his death, he said that when he chose to relocate to England in 1874, "I probably made choice of the wrong road of the two then open to me." It is sad to hear an admission of a mistaken life-choice, especially when it comes from someone who seems to have accomplished so much.

There is a Hudson Memorial Bird Sanctuary in Hyde Park, London, graced by a memorial carved by none other than Jacob Epstein, showing Rima the bird-girl flanked by several more conventional birds. Since Rima is nude, the memorial has been controversial since the day (in 1924) it was unveiled by a very startled prime minister, although thankfully, the memorial is still there. Hudson is buried in Broadwater Cemetery in Worthing, West Sussex, not too far from the gravestone of Mary "had a little lamb" Hughes.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)