Scientist of the Day - William Henry Flower

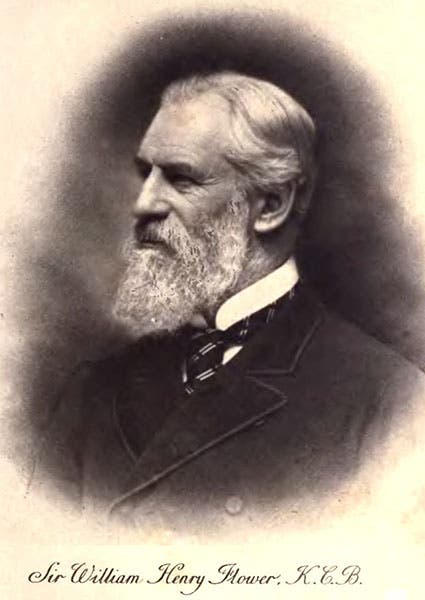

William Henry Flower, an English zoologist, anatomist, and museum director, died July 1, 1899, at the age of 67. Flower is probably the most influential Victorian naturalist that you never heard of. In an era that included Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, Thomas Huxley, and Richard Owen, it is easy for the spotlight to dwell on such celebrities and for other deserving naturalists to linger unnoticed in the shadows. We will try to refocus the limelight on Flower for a short while.

Flower was born on Nov. 30, 1831, in Stratford-upon-Avon. He had good private schooling that prepared him to study anatomy and medicine at University College, London, and he worked for a while in a hospital. He served with valor in the dreadful Crimean War in 1854 and was wounded and invalided home. He met and was befriended by London's greatest comparative anatomist, Thomas H. Huxley, and in 1862, secured the position of Conservator of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, succeeding Richard Owen. He would later (1870) succeed Huxley as Lecturer in Comparative Anatomy at the College of Surgeons, a prestigious lectureship.

Meanwhile, Charles Darwin had published the Origin of Species (1859), and Flower took to evolution immediately, although, like many, he was not too sure about the mechanism of natural selection. But Darwin pushed him in the direction of zoology, and he began publishing papers on all sorts of mammalian species, especially whales, with an emphasis, not surprisingly, on comparative anatomy. He would become president of the Zoological Society of London in 1879, and hold that position for 20 years.

Central Hall of the Natural History Museum, photograph, 1882, before exhibits were installed on the main floor and the statue of Charles Darwin was placed on the staircase landing, from Life through a Lens: Photographs from the Natural History Museum 1880-to 1950, by Susan Snell and Polly Tucker, Natural History Museum, 2003 (Linda Hall Library)

The British Museum (Natural History) had been founded as a concept in 1856, with Richard Owen as its first Superintendent, and Owen spent the next 25 years getting a separate building approved and built. It was a magnificent structure and was ready for occupancy in 1881, although it took a long time to move all the collections from Bloomsbury to South Kensington. The Natural History Museum (as we now call it) was a curious place, with four Keepers (of Zoology, Botany, Geology, and Mineralogy) who did not have to answer to the Superintendent, but rather to the Librarian of the British Museum. Owen, having overseen the building of his splendid ediface, resigned in 1883, and Flower, on the recommendation of Huxley, became the Museum's first Director.

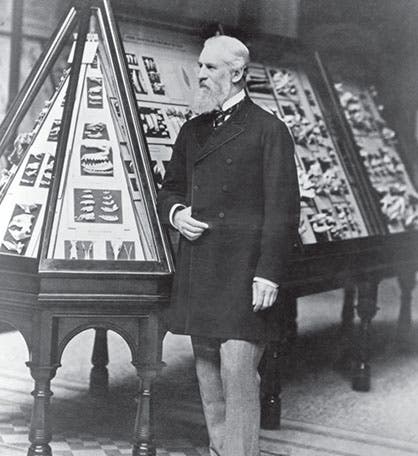

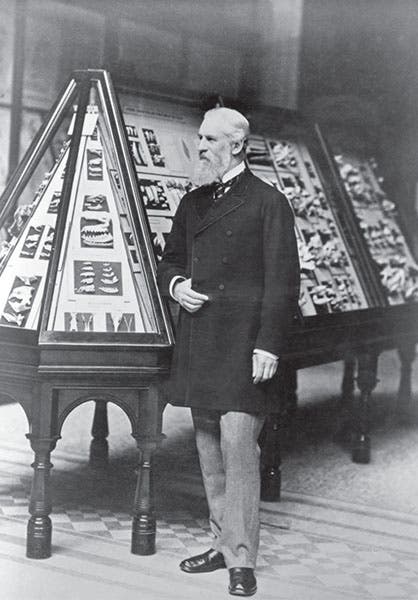

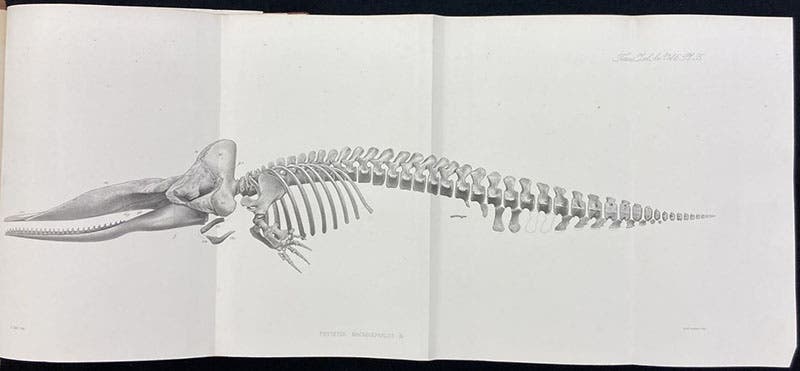

Flower was a bit flummoxed at first that he had no control over the four major departments, but he did have domain over the Central Hall, and he proceeded to show what museum exhibits should be like, something he had mastered at the Hunterian Museum. He gradually populated the Central Hall with cases that were uncrowded, with cards and labels comprehensible to working men and women, and with specimens arranged in a pleasing and color-coordinated manner. He commissioned a statue of Charles Darwin – Owen would never have approved of that – and had it installed on the landing in the Central Hall, where Darwin could overlook everything. Since the Main Hall (now Hintze Hall) was so large, he thought it not inappropriate to install the skeleton of a sperm whale (fourth image) that he had earlier studied and made the subject of a monograph (fifth image).

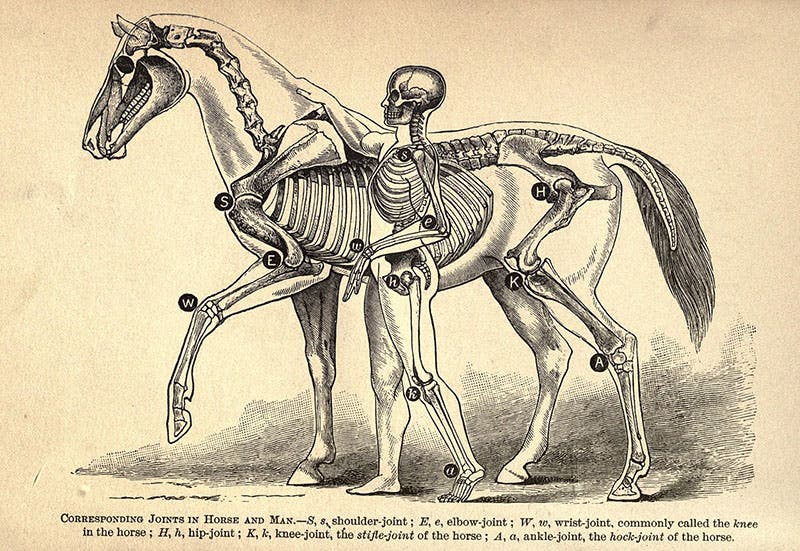

Flower was most proud of a special display that he commissioned, which showed a man and a horse, with a dog in tow; the figures were cut away to show the skeletons within. What better way to display Darwinian adaptation than to exhibit the same bones in three different species, each modified to serve radically different purposes. I could not find a photo of the mount, but there is a frontispiece in Flower's book, The Horse (1890), that achieves a similar goal (sixth image). We do not have this book; it would be a nice item to acquire.

In 1895, the Keeper of Zoology retired, and Flower took over his position, at last having a department of his own, and proceeded, in the four years of life he had left, to transform the zoology exhibits. One of his principles of display was: whenever you show a taxidermied specimen, your should place, right next to it, a mounted skeleton, so the viewer can learn a little anatomy along with zoology. Flower’s love for the explanatory power of comparative anatomy never left him.

The wounds suffered in the Crimean war began to catch up with Flower in the 1890s, as his health gradually deteriorated. He had to resign in 1898, and died on this day in 1899. But before he left, he managed to establish that a natural history museum has two sets of clientele – the public, to whom the main displays should be directed, and the scientific community, which needs to study and compare specimens. The viewing public needs only one or two representatives of a species, while the botanist or zoologist might require hundreds of each, so the two domains should be kept separate, with the public collection up front, and the professional collections, which are much more extensive, in a non-public part of the museum. This principle, which keeps public displays uncluttered, attractive, and intelligible to all, has guided natural history museum management ever since.

We have several good histories of the Natural History Museum in our collections, but I would like to call your attention to an unusual one, Life through a Lens: Photographs from the Natural History Museum 1880 to 1950, by Susan Snell and Polly Tucker (Natural History Museum, 2003), which is a collection of photographs from the Museum archives that includes the period when Flower was Director. The photographs are wonderful, reproduced in large format, and provide additional insight into Flower’s museum world. Our image of the empty Central Hall of 1882 (third image) was borrowed from this book.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.