Scientist of the Day - William Henry Fitton

William Henry Fitton, an Irish/English geologist, died May 13, 1861, at the age of 71. He attended Edinburgh University to study medicine, but became interested in geology (Robert Jameson was teaching in Edinburgh), and soon devoted most of his attention to that subject. He practiced as a physician until 1820, when he married money, and promptly moved to London and took up geology full-time.

It is curious that Fitton is little known to historians of science, even those who are quite familiar with English geologists of the period, such as Jameson, John Playfair, William Buckland, Poulett Scrope, Adam Sedgwick, and Charles Lyell. He was well respected in his lifetime, president of the Geological Society of London in the late 1820s, and looked up to by the younger Lyell. He was one of the early supporters in print of the stratigraphical work of William Smith, who was not well appreciated by most academic geologists in the 1820s.

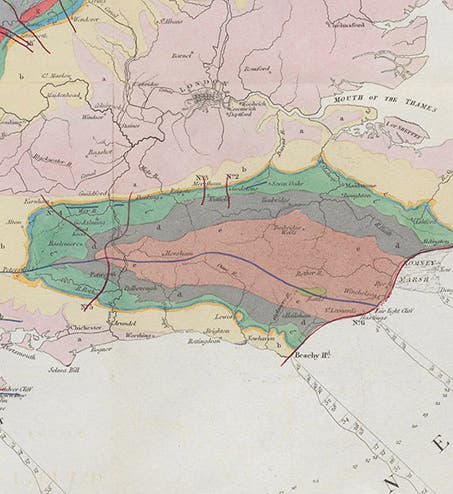

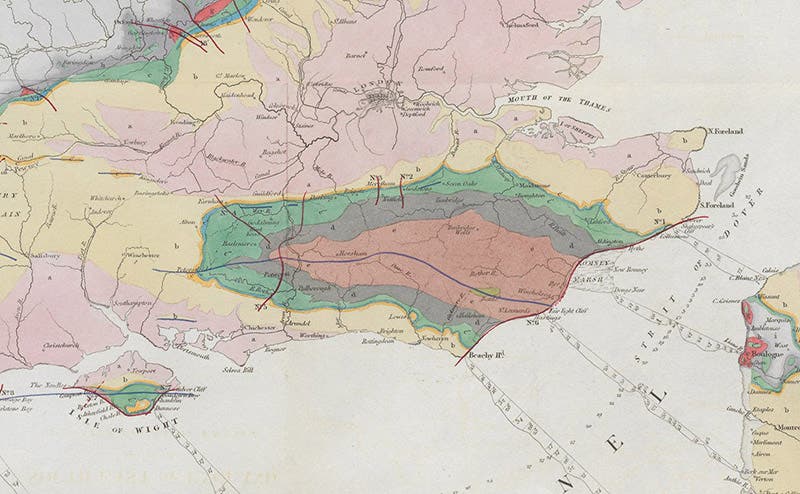

Perhaps Fitton’s reputation has suffered because he published mainly in journals, and left us only one book, A Geological Sketch of the Vicinity of Hastings (1833), which is a slight thing not intended for professionals. His two most significant contributions to geology both appeared in journals. “Observations on some of the Strata between the Chalk and the Oxford Oolite, in the South-east of England” was a lengthy monograph that was published in the Transactions of the Geological Society of London in 1836; it is often referred to as “Below the Chalk”. The paper was actually read 9 years earlier, at a Society meeting in 1827. The Chalk is the name given to the formation represented by the white cliffs of Dover, so “below the Chalk” are all those formations that are lower down and hence earlier in time. Beginning in 1824, Fitton started sorting them out, pointing out that there are two Green Sand formations, upper and lower, and underneath them is a three-part formation that he called Wealden. The Wealden is significant because it yielded non-marine fossils, indicating it was above sea level (unlike the Chalk), and some of the fossils were reptilian, including the remains of large reptiles such as those found by Gideon Mantell, that would later be labelled dinosaurs. This was really the first detailed mapping of any part of England, much more thorough than the rougher stratigraphy of William Smith.

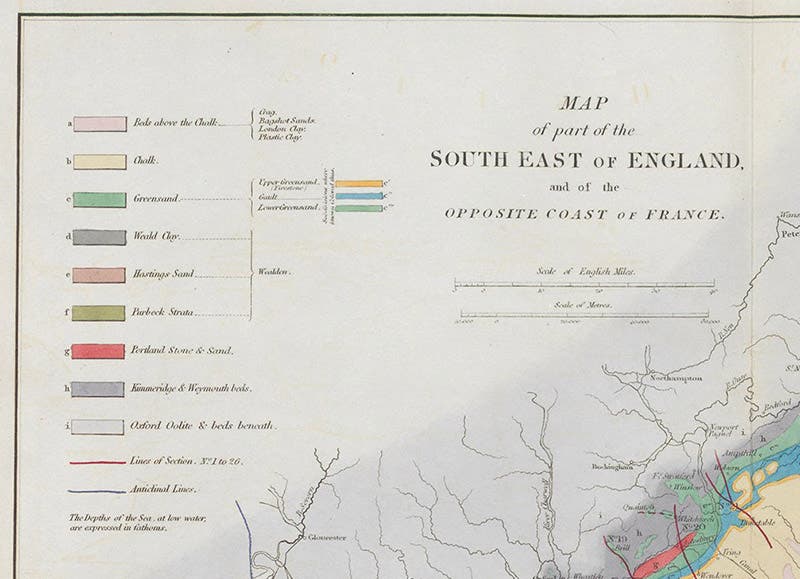

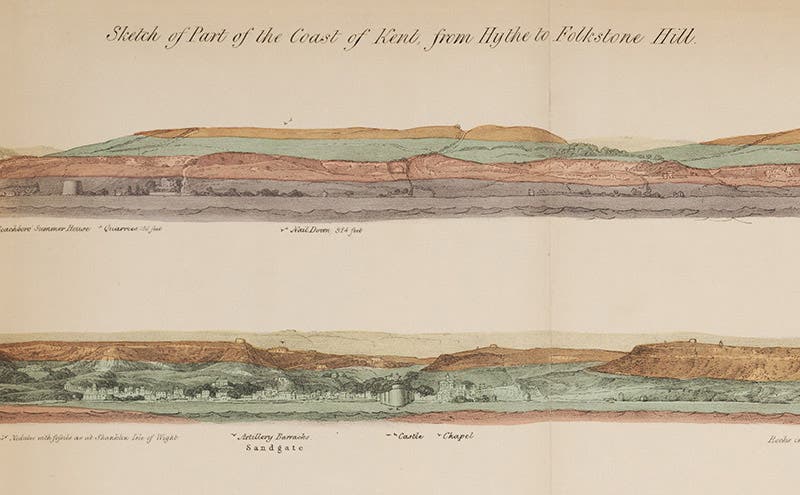

The hand-colored plates that accompany Fitton’s monograph are typical for a geological paper, but more finely executed. There is a surface map that shows the area under discussion, and a series of geological sections (imaginary vertical cuts that reveal the order of the strata). We show a detail of the map (first image), centered on the Weald and the Isle of Wight (which share some of the same formations), and the legend or key that identifies the map coloring (third image). Instead of the sections, we show a detail of an unusual folding plate that is a panoramic view of the shoreline up to Folkstone, with the formations colored the same as the map. We show a detail because the entire plate, with the panorama broken into four strips stacked on one another, is not readable at this scale (fourth image).

Fitton’s other major work was “Notes on the history of English geology,” which started out as an 1822 review of William Smith’s Delineation of the Strata of England (the real name for his map), and was then greatly expanded for publication in the London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine in four parts in 1832-33. I am not sure of this, but “Notes” may mark the beginning of the history of geology in England. We have this journal in our collections, with Fitton’s four papers; I did not have them scanned because there is nothing much to look at. But we have them.

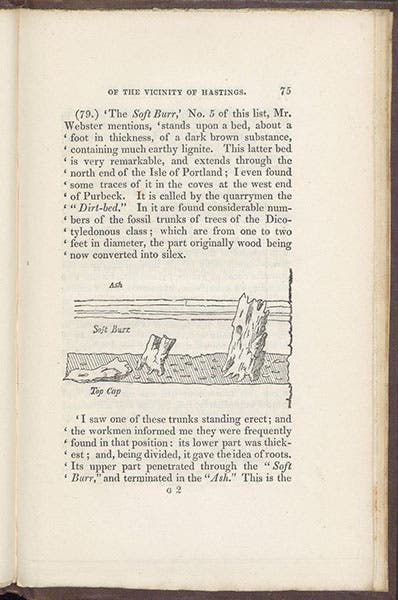

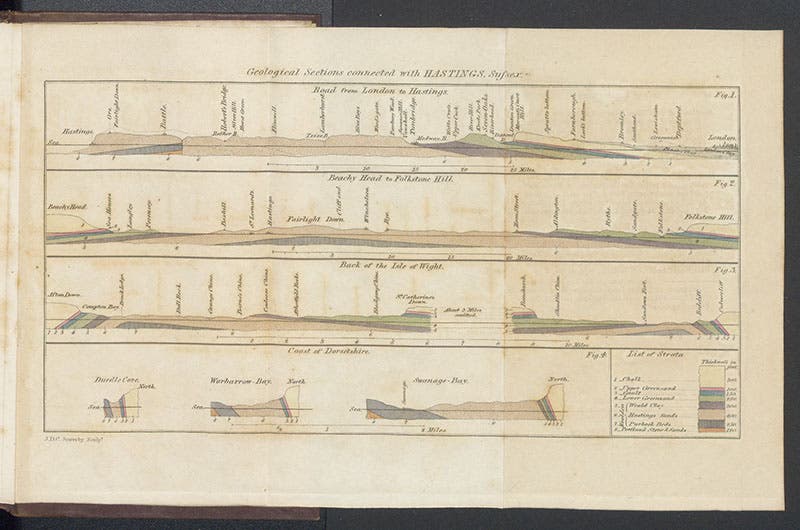

The Geological Sketch of Hastings is more photogenic, so I did have this book scanned, and we include here several images, including the handsome front cover (fifth image). There are a few text illustrations, one depicting Megalosaurus teeth and a jaw, which you can see elsewhere, and some petrified wood, which you cannot see anywhere else, so we reproduce it here (sixth image). For a frontispiece, there is a small folding plate with geological sections, and I include it here, because the sections are not detailed and you can make out some of the features even at this scale (seventh image). The top section is a cut from Hastings to London (on the right). London sits on London Clay, which sits on the Chalk, which is white and has the number 1 beneath; everything to the left is then “below the Chalk.” The Weald Clay is number 5 and is crosshatched; number 6, which is stippled, is Hastings Sand, and it occupies most of the center part of the section. At one time, the first five formations covered the Hastings Sand, but it has eroded away over millions of years, an event called the “Denudation of the Weald.” Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin would later discuss how long that might have taken.

Most rare books have a history as objects which often we are not privy to. But we know that our copy of Geological Sketch of Hastings was once in the Library of the Geological Society of Cornwall, given to them by Fitton himself, and we know this because of an inscription on the front free endpaper. We show that page for our final image.

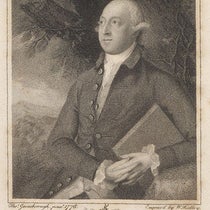

I should not have been surprised to discover that there is no portrait of Fitton in the National Portrait Gallery, nor one listed on ArtUK, but I was. The only one I know of is the one that everyone uses, including Wikipedia, in a degraded form; the one I show you comes direct from the Royal Society of London and is much nicer (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.