Scientist of the Day - William Healey Dall

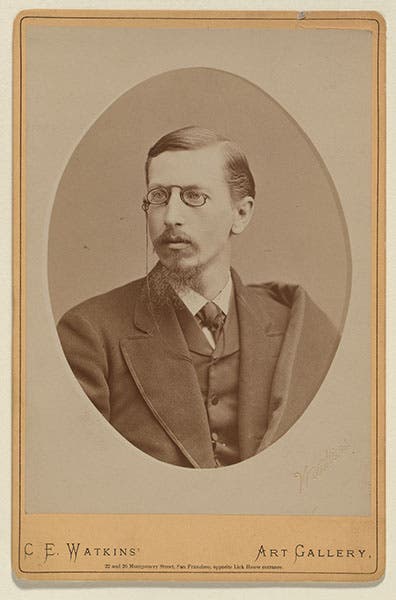

William Healey Dall, an American naturalist and explorer, died Mar. 27, 1927, at the age of 81. Born on Aug. 21, 1845, and raised in Boston by his mother, he somehow encountered Louis Agassiz at Harvard and developed an interest in mollusks and other marine fauna. At the age of just 19, he wandered west to Chicago and attended some meetings of the new Chicago Academy of Sciences, where he met Robert Kennicott, a young member of the Smithsonian Institution, but still 10 years senior to Dall, and one of the founders of Chicago's Academy. Kennicott had just been offered the leadership of a Scientific Corps that was to be attached to the Western Union Telegraph Expedition, to be sent out in 1865, and he invited Dall to come along. Dall accepted the offer.

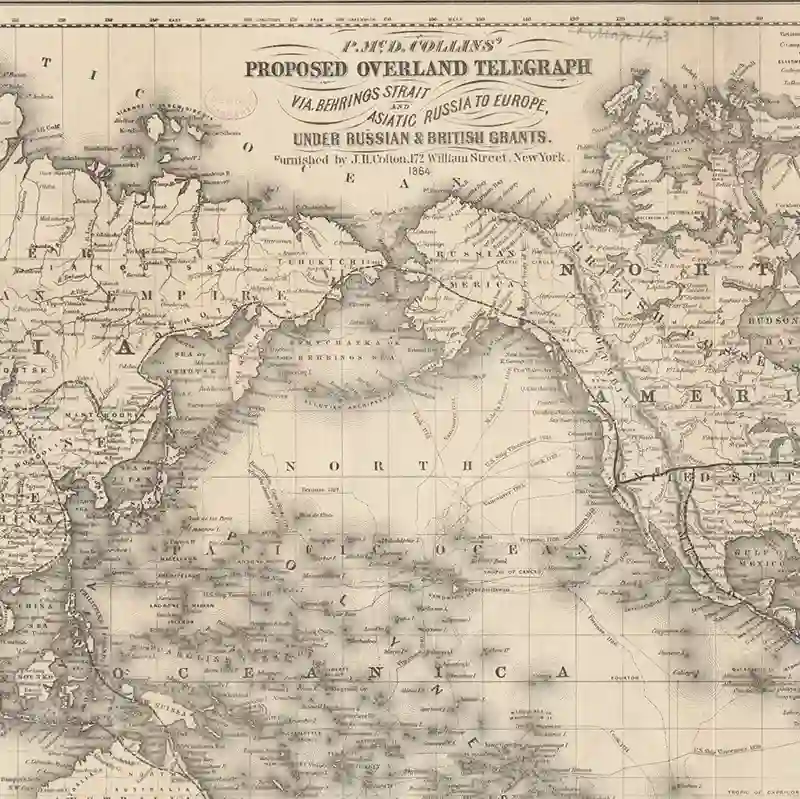

The purpose of the expedition was to scout a path for, then build, a telegraph line, up through Alaska, underneath the waters of Bering Straits, and across Russia to St. Petersburg. A consortium had been trying to lay an Atlantic Cable for 10 years now, without success, so this was a different approach to connecting the U.S. and Europe telegraphically. Since they would be making their way through unexplored territory most of the way, it was thought that there ought to be naturalists and geologists along as part of the expedition, hence the inclusion of Kennicott and Dall and several others.

The expedition headed north in 1865, and was well into Alaska by 1867 – there was even a marine contingent, led by Charles Scammon, who would later write an important book on the sea mammals of the Northwest coast. Kennicott died quite unexpectedly in 1866, just 31 years old, and young Dall took over leadership of the Scientific Corps; he was just 21. In that same year, two Atlantic telegraph cables were successfully laid and put to use, rendering an Alaskan cable superfluous. In 1867, the Western Union Telegraph Expedition was abandoned.

For Dall, the abrupt termination of his first exploring venture was a disguised blessing. He had collected mollusks, living and fossil, for 3 years, and he began to publish papers and monographs on a subject of which he was now the world expert. He published a book on Alaska in 1870 (which we do not have in our collections). He had taken a great interest in the native tribes they encountered in the Northwest, and he published a pioneering work in ethnography in 1877 (which we DO have, in our Government Documents collection, sixth image). He went on to work for the U.S. Coast Survey, and then, in 1884, he joined the new U.S. Geological Survey as their chief paleontologist, a position he would hold until 1925. He was also the unofficial paleontologist for the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C. (now part of the Smithsonian Institution).

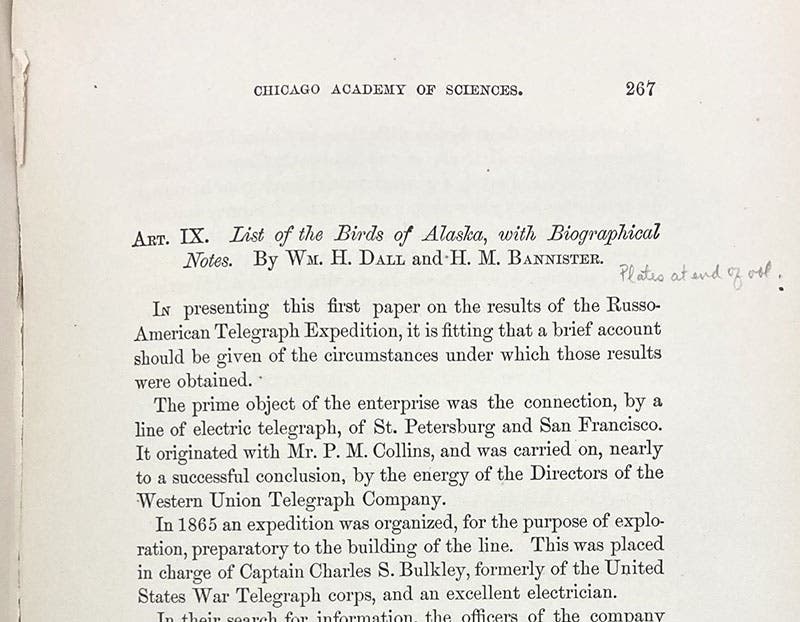

We have 12 book-length publications by Dall in our collections, most of them on shells or mollusks, which are not particularly interesting to non-malacologists. We also have the first volume of the Transactions of the Chicago Academy of Sciences, which includes, in addition to some selections from Kennicott’s diary, a paper by Dall on Alaskan Birds. His paper is just a list of 212 Alaskan birds (fourth image), but there is an appendix to Dall’s paper by Spencer Baird that includes some lovely colored lithographs of birds by Edwin Sheppard, which are often assumed to be part of Dall’s paper, but they are not. We show you one of the plates anyway, since Baird named it after their deceased colleague, Scops kennicotti, Kennicott’s Owl (fifth image).

The monograph on the native American tribes of the northwest, co-written with George Gibbs, is also of interest because of the two colored printed maps folded up in a pocket at the end. The one showing Alaskan tribes is too brittle to unfold, but the one Dall did for Gibbs’ monograph on the tribes of Washington Territory is in good condition, and we show it here (seventh image) as well as a detail of the legend (eighth image), where you can see the attribution to Dall.

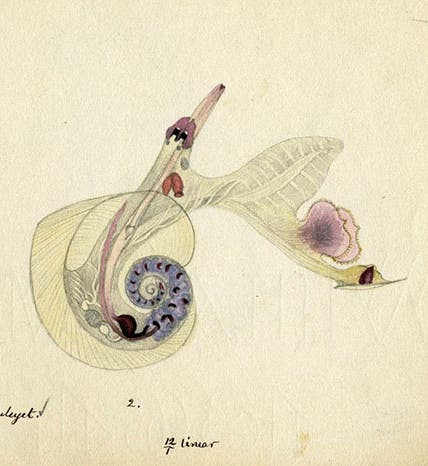

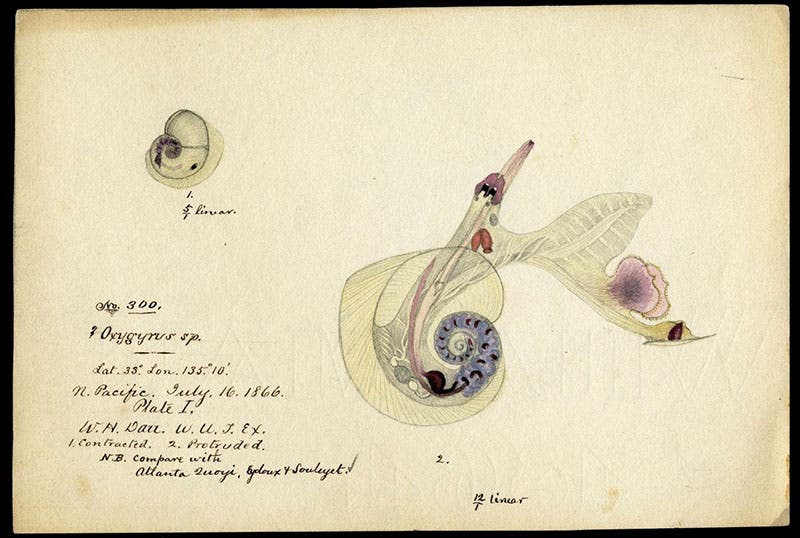

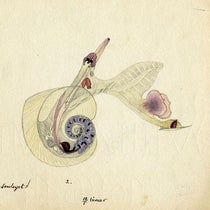

The Smithsonian Institution has at least one (perhaps more) of the diaries that Dall kept on the Alaskan expedition, and they have tantalizingly put just one opening online, showing two sketches by Dall of forts in the Yukon (ninth image). I also found in the Smithsonian archives online, some drawings of mollusks by Dall, which are very well done, and we inserted one as our opening image

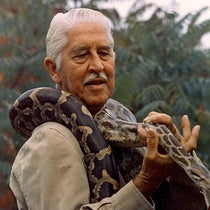

After passing away on this date in 1927, Dall was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass, where many great American scientists have been laid to rest, including Dall’s contemporaries Louis Agassiz, Asa Gray, Augustus Gould, and Jacob Bigelow, who conceived the cemetery in the first place. A portrait of Dall in his seventies shows that he aged very well from the tentative young man of the 1860s (last image). It is too bad that Kennicott never had the chance to grow old.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.