Scientist of the Day - William Gorgas

William Crawford Gorgas, an American Army physician, was born Oct. 3, 1854. Gorgas was chief sanitary officer in Havana when the Army sent in a commission to investigate the cause and prevention of yellow fever. The head of the commission was Maj. Walter Reed, who, building on the work of Carlos Finlay, a Cuban physician, was able to show that yellow fever is carried by a species of mosquito, and confirm that malaria is also carried by a mosquito, although a different species. Finlay had suggested, and Reed confirmed, that to get rid of yellow fever, you need to get rid of the mosquitoes. Gorgas was convinced by Reed’s experiments and demonstrations (although many others were not, including the Surgeon General’s office back in Washington).

So when Gorgas was appointed Chief Medical Officer for the newly-established U.S. Panama Canal Commission in 1904, he knew just what he wanted to do. The unsuccessful French Panama Canal project of the 1880s had been thwarted by many factors, but yellow fever and malaria had played a major role in depleting the French work force. Get rid of yellow fever and malaria, and the canal project, so Gorgas believed, had a fighting chance. Gorgas was unable to implement his desired controls immediately, as he could not get the funding from Washington, where it was thought that mosquito eradication was a waste of time and money. But when John Stevens became the new Chief Engineer in 1905, Gorgas and Stevens were able to convince President Roosevelt that Gorgas’s proposed sanitary reforms were essential.

Once the funds were approved, Gorgas got to work immediately. The reforms he implemented included:

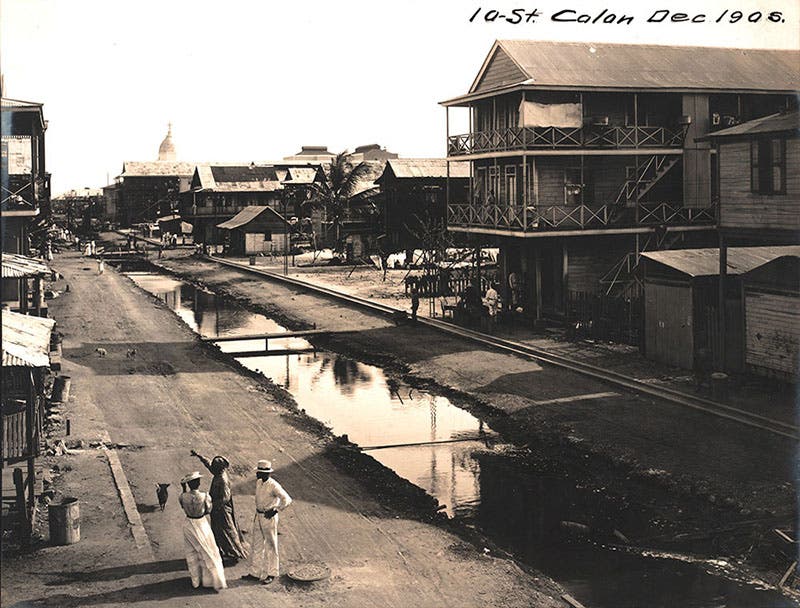

- draining all swamps and standing water where the mosquito larvae breed (first image)

- using squads equipped with oil sprayers to coat the water that cannot be drained with a thin film of oil, which kills mosquito larvae (fourth image)

- isolating all victims of malaria and yellow fever in screened-in wards, so that mosquitos cannot bite them and spread the disease (third image)

- fumigating all homes and living areas with burning sulfur

- screening in all sleeping areas

Thousands of sanitary workers implemented these methods in 1905 (fourth image). The effect was almost immediate. Yellow fever cases went down markedly; the last canal worker to die of yellow fever caught the disease late in 1906, and that was it. There were no more fatal cases after that–yellow fever had been effectively eradicated in the Canal Zone.

Gorgas may not have discovered how yellow fever is transmitted – Reed and Findlay deserve that credit – but he certainly demonstrated how to put that knowledge to effective use. It is very likely that if yellow fever had continued to run unchecked among the U.S. canal workers, as it had with the French, then the U.S. Canal effort might well have met the same fate as that of France. Gorgas deserves as much credit as the engineers for the success of the Panama Canal project.

Our Library has an extensive collection of materials related to the U.S. Panama Canal Commission, known as the A.B. Nichols Collection. A.B. Nichols was the Office Engineer for the Commission from 1904 to 1914, in charge of keeping maps, records, and photographs of the enterprise, and he put together 92 volumes of materials, much of it unique. The collection was given by his daughter to the Engineering Societies Library, and it came to our Library when we acquired the ESL in 1995. It formed the basis for our 2014 exhibition commemorating the centennial of the completion of the Canal: The Land Divided, the World United: Building the Panama Canal. The exhibition is available online, and all of the images shown here were taken from the Nichols collection.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.