Scientist of the Day - William Diller Matthew

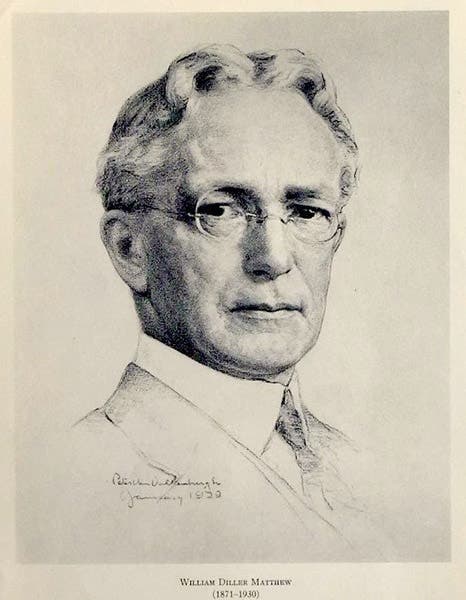

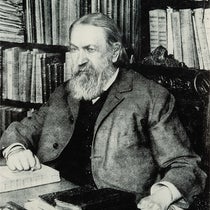

William Diller Matthew, an American paleontologist, was born Feb. 19, 1871, in Saint John, New Brunswick. He did his graduate work in geology at Columbia University in New York City, where he was attracted to the instruction of Henry Fairfield Osborn, who had recently become curator of vertebrate paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History and had simultaneously joined the faculty at Columbia. Osborn liked what he saw in Matthew, and before long, Matthew was working at the museum as assistant curator to Osborn.

Dinosaur studies entered a new era at the end of the 19th century, as the two irascible giants of 19th-century dinosaur foraging, Edward D. Cope and Othniel C. Marsh, passed away in 1897 and 1899 respectively. Cope and Marsh had detested each other, and their competition for dinosaur remains was fierce and unscrupulous. A more civilized climate ensued almost immediately, even though there was a new competitor, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, and Matthew was there at the outset, which was fortunate, since he was a civilized gentleman. Field workers from the American Museum in 1898 had discovered a promising dinosaur site near Como Bluff, Wyoming (Marsh’s old stomping grounds), which was called Bone Cabin quarry, because dinosaur bones on the surface were so prolific that one economical sheepshifter had built an entire cabin from fossil dinosaur remains. In 1899, Walter Granger, a colleague of Matthew at the museum, discovered a nearby site, Nine Mile quarry, where the exposed rock seemed to contain most of the skeleton of a large sauropod.

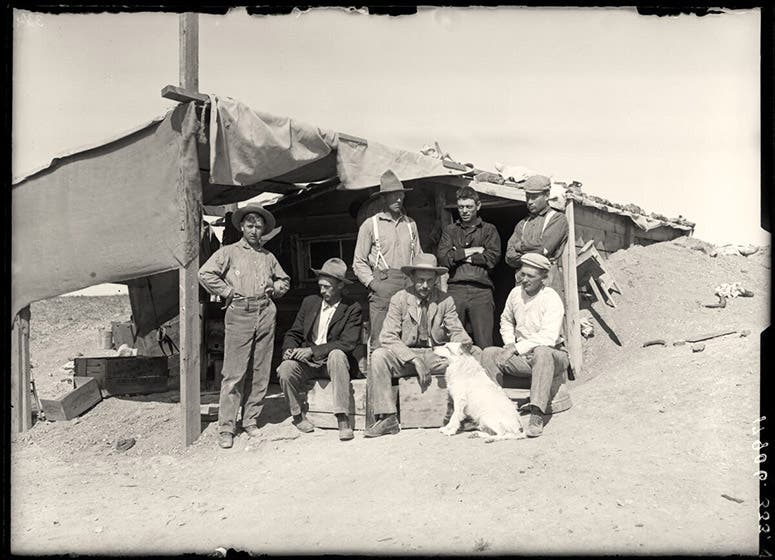

Matthew joined Granger at Nine-Mile quarry in 1899, and with the help of Peter Kaisen, Bill Thomson, and Richard Swann Lull, they excavated, plastered up, crated, and shipped back by rail the bones of what would be confirmed as a Brontosaurus. The museum has photographs of the excavation – our third image shows Matthew at right, with Kaisen and Lull – and a more famous photograph (fourth image) captured a day when Osborn came out to check on the dig. It shows all our participants – Matthew is seated at the right of the front row, with Osborn in the center, petting Jack the dog.

Marsh had discovered the first Brontosaurus skeleton decades earlier and had shipped his specimen back to the Peabody Museum at Yale, but they had no room to mount it, and so it stayed in its cases. The AMNH wasted no time in mounting their specimen. Matthew was in charge of preparing the mount, although the actual work was done by the preparation staff, headed by Adam Hermann, and the mount was opened to the public in 1905. Several photographs of the mount in progress survive; one of them (fifth image) shows Matthew examining the shoulder section of the restoration.

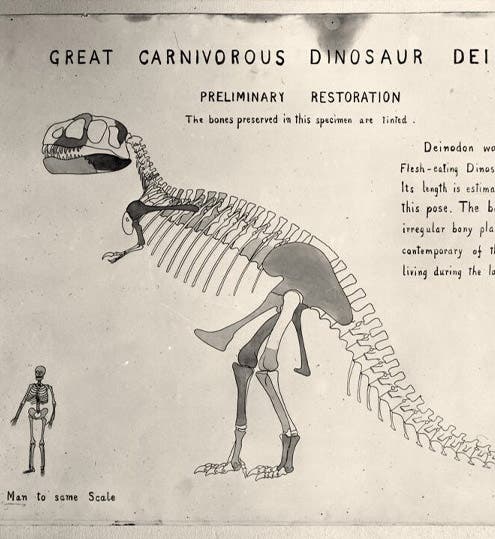

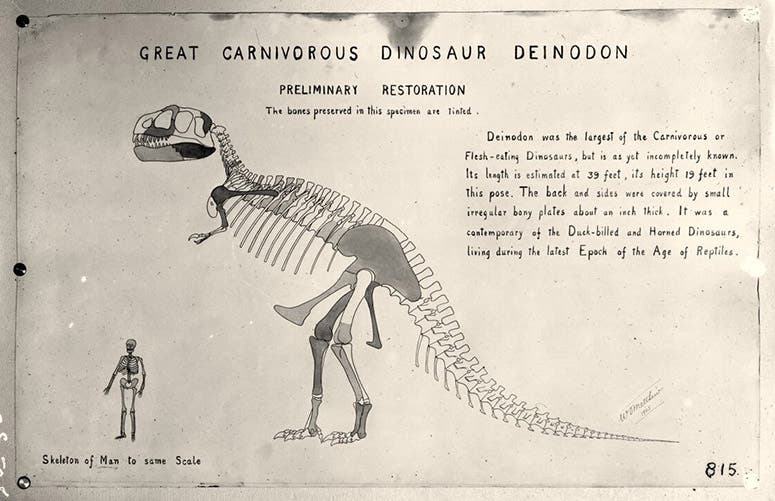

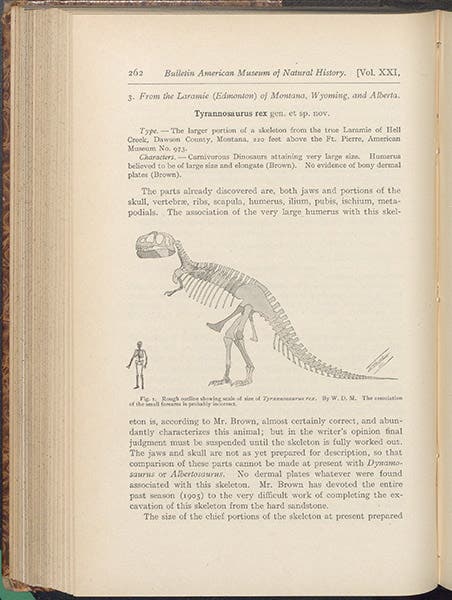

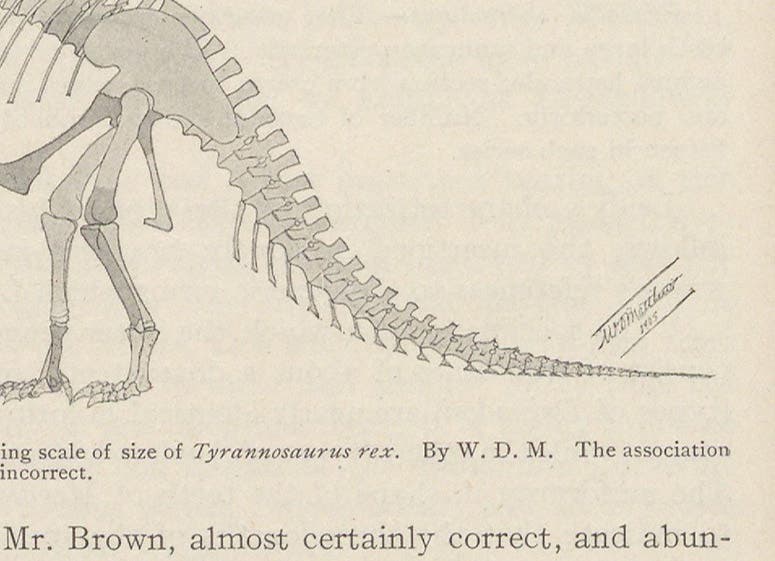

Another contribution of Matthew to dinosaur lore came with the first description of Tyrannosaurus rex in 1905. Matthew was not involved in the discovery and excavation of T. rex – that was the work of Barnum Brown, who discovered the first T. rex specimen in Hell Creek, Montana, in 1902, and unearthed it with the help of Peter Kaisen from the museum. Osborn took upon himself the task (and prestige) of naming and describing the formidable carnivore, but he asked Matthew to provide a reconstruction on paper for the publication, which appeared in the Bulletin of the museum in 1905. Matthew’s “preliminary restoration” survives in the archives of the museum (first image). Note that it carries the name Deinodon – “terrible tooth” – apparently a working nickname at the time of the drawing. By the time of publication, the name had changed, but not the restoration, which was printed as a modest-sized line engraving in the middle of a page of text (sixth image). In an enlargement (seventh image), the signature above the tail is readable: “W.D. Matthew 1905.”

Matthew was also the museum person responsible for directing the artwork of Charles Knight. Knight was a freelance artist who began supplying watercolor restorations of prehistoric animals to the Museum in 1894, and he was rapidly becoming the foremost dinosaur and early mammal artist in the world (and the great-grandfather of every paleo-artist working today), but he was not a paleontologist, and needed someone to tell him about anatomy and habitat, and after 1899, Matthew filled that role, and did so for the next decade and a half. Knight was always full of paise for the technical expertise provided to him by Matthew.

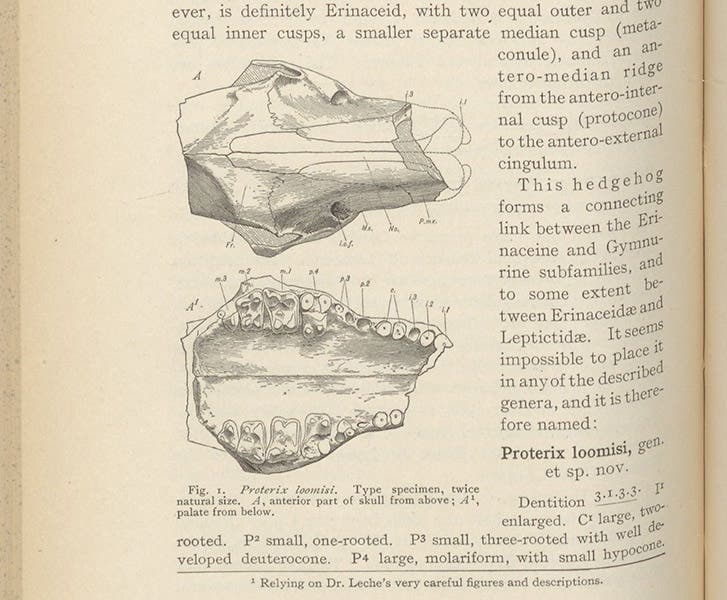

Well, all this makes it sound as though Matthew was a true dinosaur man. In fact, he was not. His own research interest was in early mammals, the tiny creatures from the early Cenozoic that took possession of the landscape when the dinosaurs departed. His own high reputation among modern-day paleontologists stems from his publications on mammals, not from his mounting of Brontosaurus or his drawing of T. rex. The reason we focus on dinosaurs here is because I know much more about the history of dinosaur discovery, and because most readers find dinosaurs more accessible than early mammals. But there is one mammal paper by Matthew I thought I would mention, since it involves a mammal dear to our library, the hedgehog. In 1903, Matthew announced in the museum Bulletin that the first fossil of an American hedgehog had been found in South Dakota by F. B. Loomis of the museum. In his paper, Matthew described the insectivore, named it Proterix loomisi (“Loomis’s proto-hedgehog”), and provided a drawing of its skull (eighth image). Our library’s mascot and emblematic animal is a hedgehog, and our house journal is called the Hedgehog. So Matthew contributed, in a way, to a better understanding of our own prehistory.

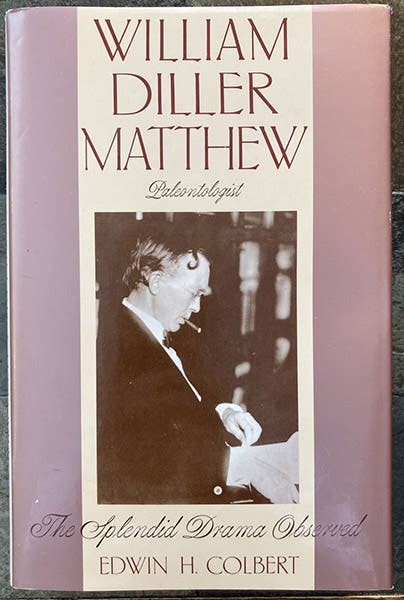

Matthew and Osborn had never really gotten along, after the early years – Osborn could be pretty overbearing – and Matthew finally left the museum, in 1927, when he received an offer from the University of California at Berkeley to build a department of vertebrate paleontology and establish a museum. He made a good start, but he suffered kidney failure in 1930 and died, only 59 years old. He left behind a daughter, Margaret, who was a gifted paleo-artist, and who married Edwin Colbert, an eminent paleontologist himself and a historian of dinosaur discovery. That was fortunate for Matthew’s legacy, for Colbert wrote a very readable biography of his father-in-law: William Diller Matthew, Paleontologist: The Splendid Drama Observed (Columbia Univ. Pr., 1992), which is not only the source for much of this column, but whose dust jacket provides another fine portrait of William D. Matthew (last image).

Dust jacket, William Diller Matthew, Paleontologist: The Splendid Drama Observed, by Edwin C. Colbert, Columbia Univ. Pr., 1992 (author’s copy)

Thanks to the American Museum of Natural History for making so many of their historic photographs available online, greatly enriching a post like his.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.