Scientist of the Day - William Clark

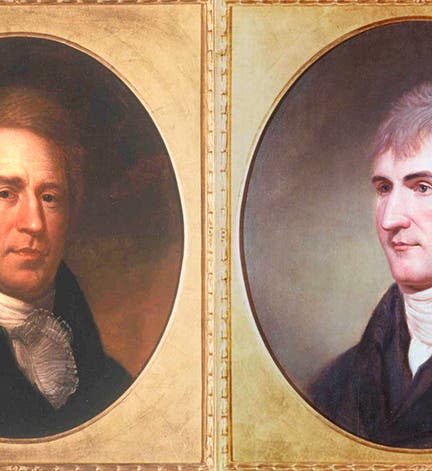

William Clark, American explorer, was born Aug. 1, 1770. In the 1790s, he served in the Army in Ohio and met Meriwether Lewis; the two developed a bond of mutual respect. When Lewis was asked by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803 to head up an expedition to explore the Missouri River in search of a passage to the Pacific, Lewis promptly asked Clark by letter if he would be a co-leader of the venture (Lewis may have been prompted by Jefferson to do so, since Jefferson was very fond of Clark’s older brother, George Rogers Clark), and Clark consented. Although he was only given the rank of lieutenant, whereas Lewis was a captain, Lewis considered him of equal rank and always referred to him as Captain Clark.

The Lewis-and-Clark expedition, or, as historians call it, the Corps of Discovery, headed upriver from the mouth of the Missouri on May 14, 1804, overwintered with the Mandan in North Dakota in 1805, crossed the continental divide on Aug. 26, 1805, reached the mouth of the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean on Nov. 20, and arrived back in St. Louis on Sep. 23, 1806, to great acclaim. The passage over the continental divide was difficult and not at all what Jefferson had hoped for; there was to be no easy northwest passage to the coast. But in terms of territory explored and mapped, new animals and plants discovered, Native American peoples encountered, and in establishing an American presence in territories sought by England, the expedition was a resounding success.

Lewis was the naturalist on the expedition and had received special training arranged by Jefferson in gathering specimens and in the use of surveying instruments and sextants. Clark received none of this, since he came so late to the party. But he had his own special strengths. He was a gifted cartographer, and all the maps that came out of the expedition were his. He was a committed journal keeper, rarely failing to make a daily entry, whereas Lewis once went for almost 11 months without writing anything. Clark was also the better leader of men; in the face of continual minor rebellions and derelictions of duty, Clark was the one who held the group together for two and a half years. Clark also had a special admiration for their translator, Sacagawea, and praised her courage and quick thinking in several journal entries, whereas Lewis seemed to have little use for the Shoshone woman.

It had always been assumed that Lewis, Jefferson's first choice for the Corps, would write the narrative of the expedition, but when Lewis committed suicide in 1809, that burden fell on Clark. Clark knew he could not do it himself – he had had little formal education – but he found a young man in Philadelphia, Nicholas Biddle, who agreed to take Clark's journals and those of Lewis and craft an account from them, and Biddle really did a very good job. The narrative was published in Philadelphia in 1814 in two volumes as History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark. An expanded edition under a different title was published in London in 1817 in 3 volumes, and that is the set we have in the Library. Unfortunately, it lacks the frontispiece map, which aggravates us more than a little. We never buy works that are lacking anything, but our copy came to us this way when we acquired the Library of the Engineering Societies of New York in 1995, so we are rather stuck with it. I must say, however, that in every other way it is an exemplary copy. But we do wish we had that map.

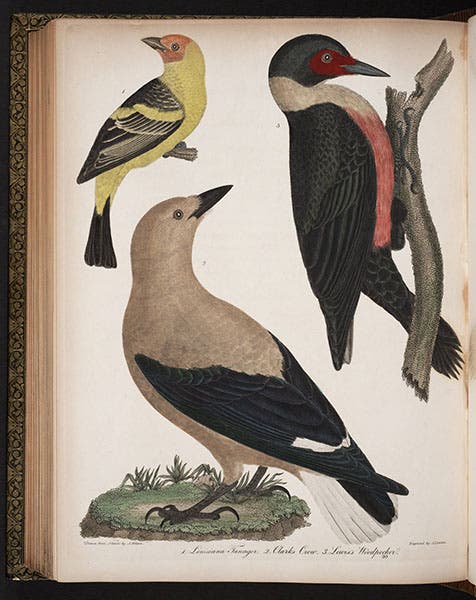

When we wrote about Meriwether Lewis several years ago, we devoted some space – probably too much – to discussing Lewis's woodpecker, a new bird discovered on the expedition and named by Alexander Wilson after Lewis. Well, in August of 1805, Clark found his own new bird, with a white body and black wings, that fed almost exclusively on pine nuts. A specimen of this bird was also brought back and deposited in the American Philosophical Society, and Wilson included it as well in his American Ornithology (1808-11), naming it Clark's crow (second image); it is now usually called Clark's nutcracker. The original drawing that Wilson made, which was used for the engraving, still survives in the archives of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia (third image).

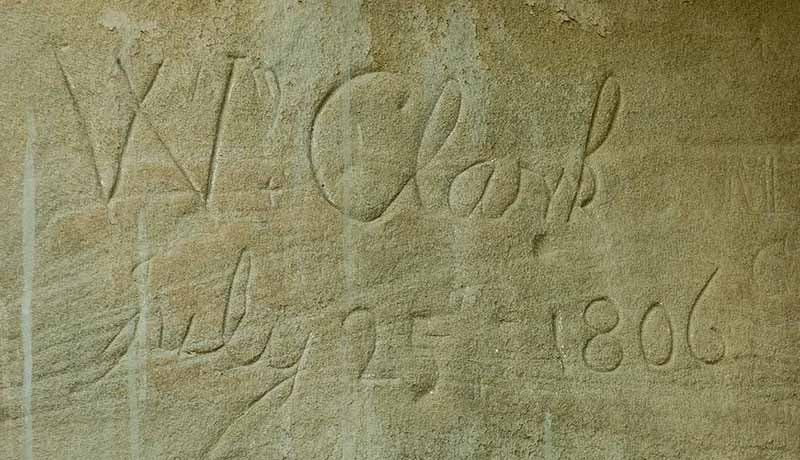

It has been often noted that there is only one physical remnant that shows the progress of the Corps of Discovery to the Pacific Coast and back, and it is to be found at Pompey’s Pillar in southern Montana (named by Clark after Sacagawea’s young son, Pomp) (fourth image). The Corps stopped there on their way back to St. Louis, and one of the men carved his name and date into the rock, an inscription that may still be seen today. Fittingly for our subject of the day, the inscription reads: “W Clark July 25 1806” (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.