Scientist of the Day - William Buckland

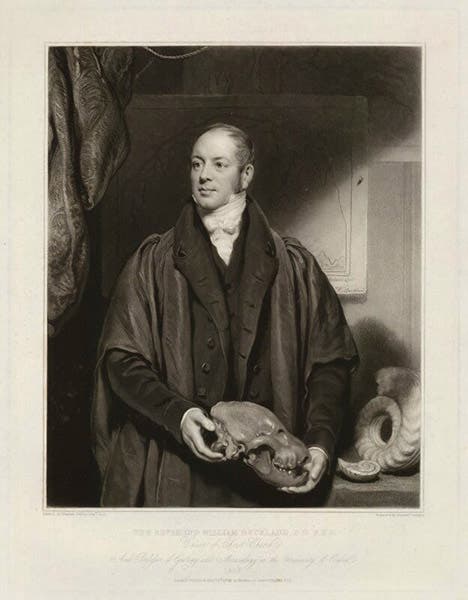

William Buckland, an English geologist, fossil collector, and Anglican priest, was born Mar. 12, 1784, in Axminster, Devon. He became the very first professor of geology in all of England when he accepted the newly created Readership in Geology at Oxford in 1818. He was, initially at least, a catastrophist like Georges Cuvier, believing that enormous floods were the primary causal agents in forming and reforming the Earth's surface. But he was also one of the first to attempt to reconstruct ancient environments using fossils, as he did with Kirkdale Cave in 1822. We discussed his cave geology in our first post on Buckland.

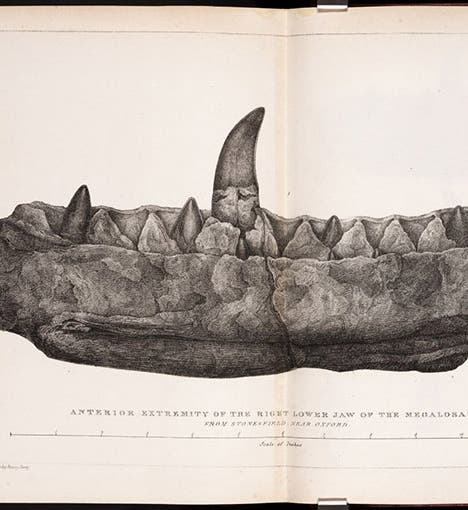

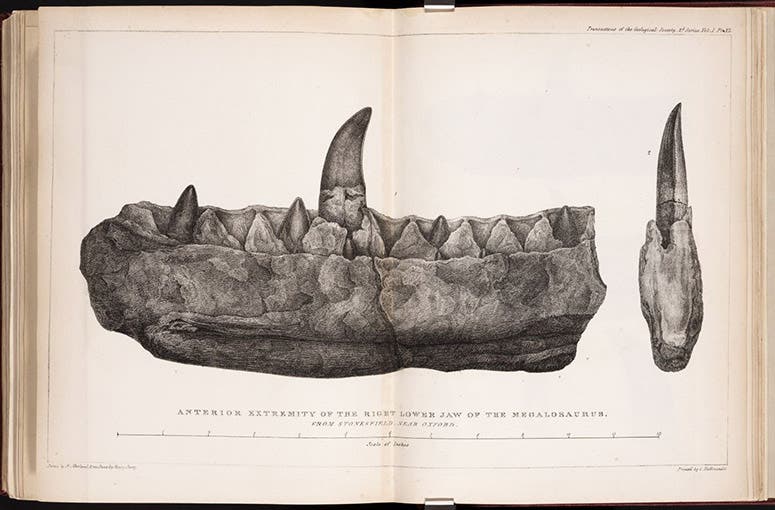

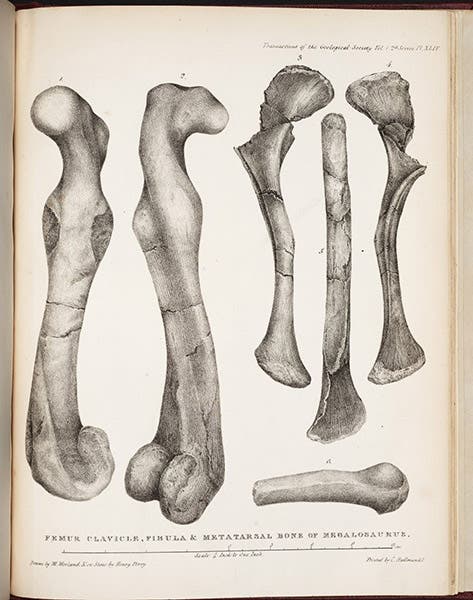

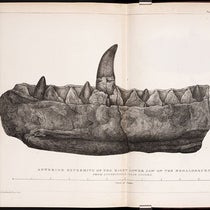

Today we look at Buckland's role in the history of dinosaur discovery, where he happens to occupy the pole position. Sometime around 1815, he began to acquire a few large fossil bones from a quarry in Stonesfield, about 15 miles northwest of Oxford. These included a femur, a fibula, some vertebrae, a clavicle, and a 12-inch chunk of lower jaw, with large knife-like teeth in place. He had drawings made by a young woman fossil collector and illustrator, Mary Morland, and circulated them to colleagues, but no one knew what Buckland had found.

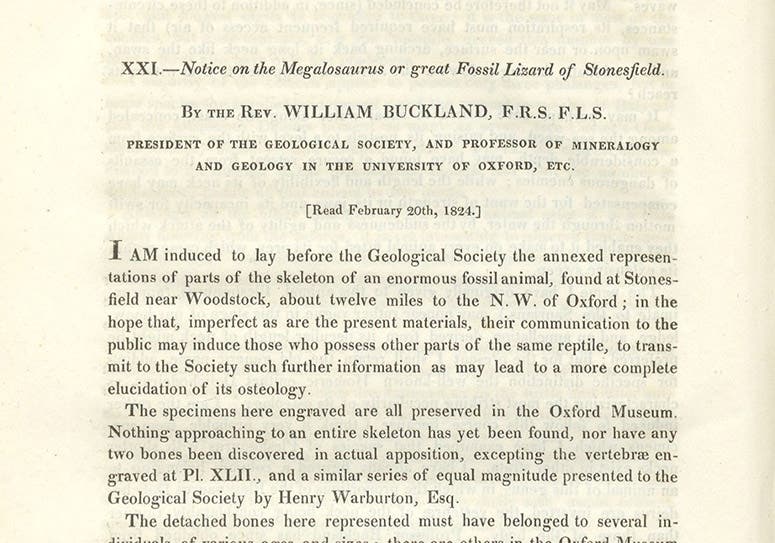

In 1824, Buckland became President of the Geological Society of London, and he used the occasion to finally read a paper on his find. He concluded that the bones were the remains of a large extinct reptile, which he named Megalosaurus, "very large lizard." He estimated its length at 40 feet, and its occupation as meat eater. His paper was published in the Transactions of the Society, along with Miss Morland's drawings. The life-size lithograph of the jaw is especially impressive (first image). A year later, Miss Moreland became Mrs. Buckland.

Megalosaurus was a singularity for only a short while. Gideon Mantell found and announced another extinct giant reptile in 1825, which he called Iguanodon, then discovered several more complete specimens, and finally, in 1832, unearthed a third and quite different Mesozoic reptile, which he called Hylaeosaurus. In 1842, Richard Owen lumped all three into a new sub-order of reptiles, the Dinosauria. Buckland had discovered the first.

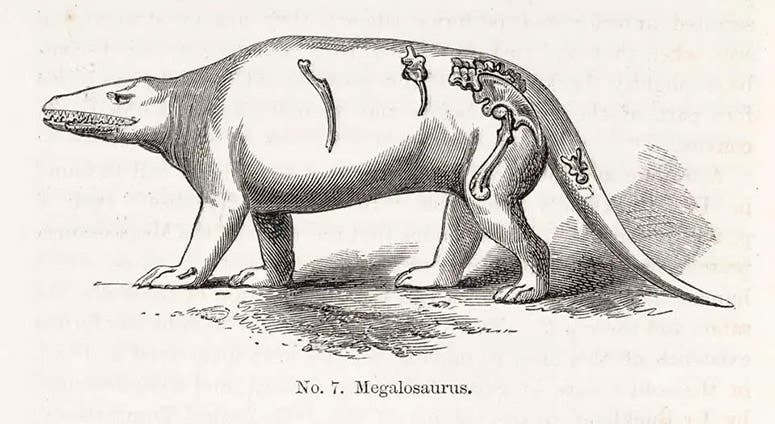

Buckland never attempted a reconstruction of Megalosaurus, but Owen did, in 1854. He imagined the dinosaur as a bulky quadruped with a small hump on its shoulders, like a giant water buffalo (fifth image). Note that Owen carefully indicated in his drawing the positions of the actual bones that had been discovered, and that there were not many.

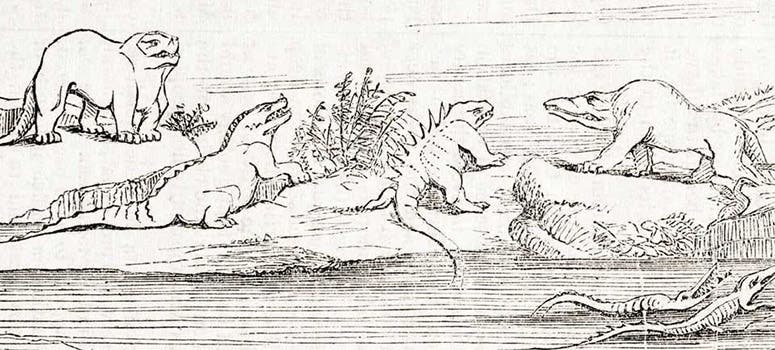

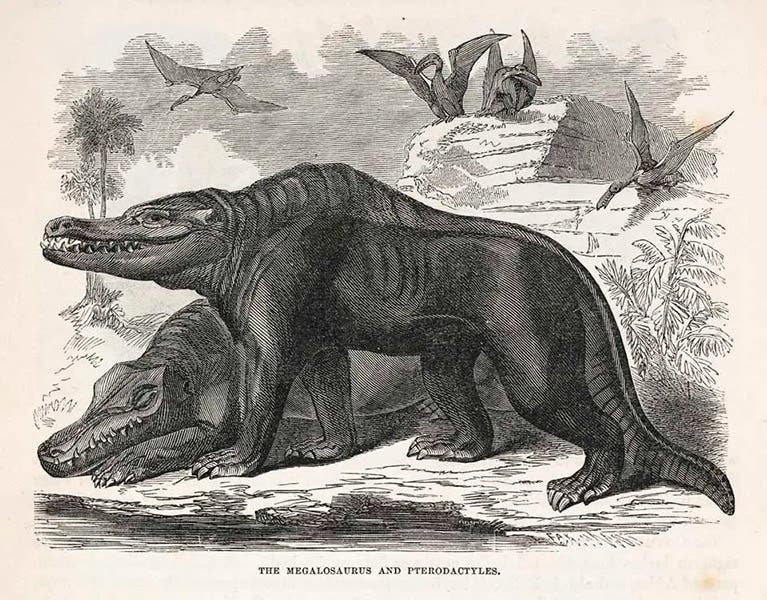

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins gave concrete form to Owen's reconstruction, quite literally, when he had a full-size concrete-over-iron replica made for the reopening of the Crystal Palace after its move to Sydenham in 1854. In a drawing by Hawkins of the new dinosaur tableau (sixth image), Megalosaurus is at far right, with 2 iguanodons at left and the spiky Hylaeosaurus in between. And when Samuel Goodrich published his Illustrated Natural History in 1859, he provided an image of Megalosaurus, taken from Hawkins’ model (seventh image).

Buckland is something of a hero to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, as indeed he should be, since he was the source of many of their specimens. There is a fine marble bust of Buckland in the museum, which you can see here. And if you ask nicely, perhaps they will show you the original fragment of Megalosaurus jawbone, which looks much more formidable in person (eighth image) than it did in Mary Morland's delicate drawing.

There is a more extended discussion of Buckland's Megalosaurus, and all the other dinosaurs and early collectors and portrayers mentioned here, in our online exhibition catalog, Paper Dinosaurs. You might begin with the first item (Buckland) and advance through item seven, which covers dinosaurs in England up through 1859.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.