Scientist of the Day - William Borlase

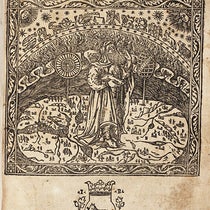

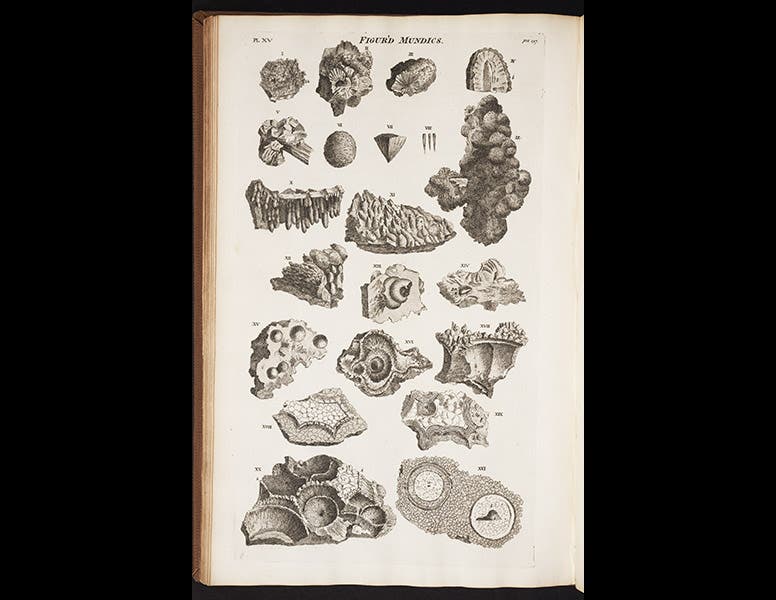

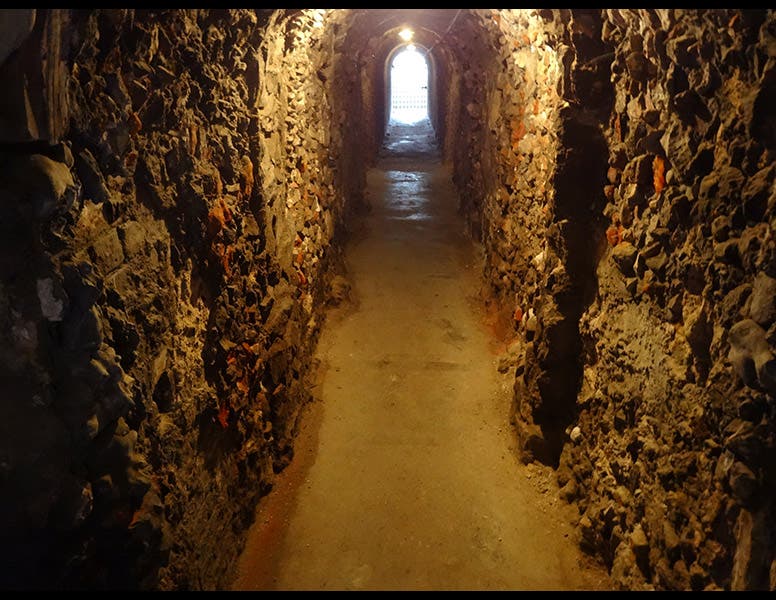

William Borlase, an English naturalist and antiquary, was born Feb. 2, 1696. Borlase lived and died in Cornwall, where he amassed a large collection of fossils, gems, antiquities, and natural history objects. Eventually he published The Antiquities of Cornwall (1754) and The Natural History of Cornwall (1758); we have the latter work in our History of Science Collection (third image). It is a large folio, and many of the engravings depict manor houses and estates and other scenes that seem to have spilled over from his Antiquities book. But there are quite a few plates that depict minerals (first image), crystals, fossils, and assorted stuffed birds, amphibians, and small mammals. The prize illustration in the work is a large folding map of Cornwall (fourth image). At this scale, you probably cannot pick out Borlase’s home village of Ludgvan, out on the tip, just north-east of Penzance.

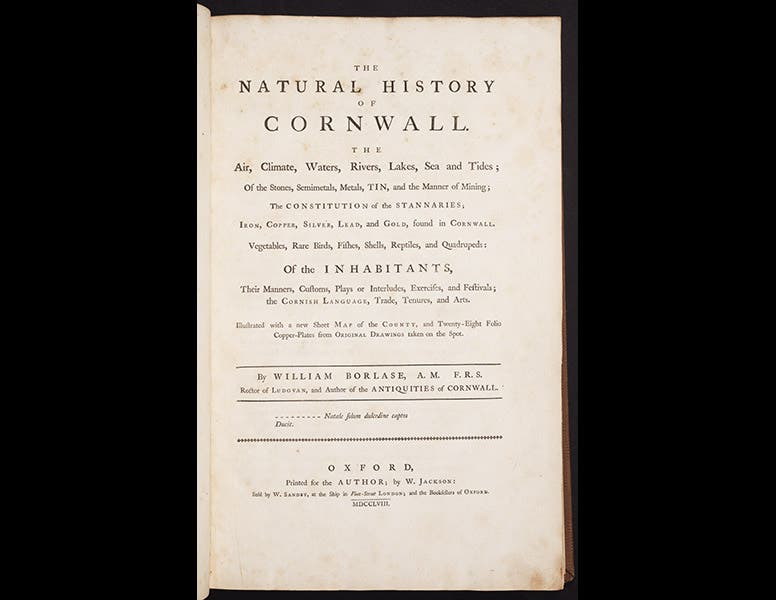

Most of Borlase's collection would end up in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. But not all of it. Borlase was a lifelong friend of the poet Alexander Pope, and in the 1720s, Pope built a house on the Thames at Twickenham, just west of central London. Pope installed a garden, naturally--everyone had a garden--but as he had occasion to dig under the road to get to the garden from his house, it occurred to him to turn the underground passage into a grotto, complete with running water from a spring discovered during the excavation. Grottos were moderately popular in Italy at the time, but were still uncommon in England.

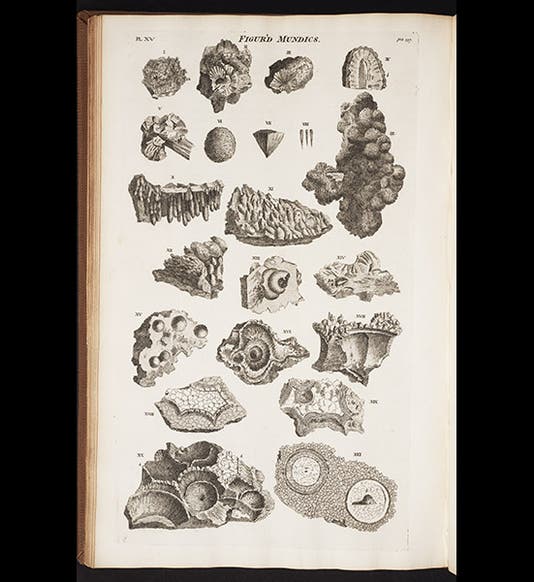

Some years went by before it occurred to Pope to decorate his underground grotto with subterranean objects, such as minerals, gems, stones, and carvings. Friends sent him minerals and antiquities from all over England, but the bulk of the specimens in Pope’s grotto were happily supplied by Borlase. We have just one contemporary view of the grotto, an engraving made in 1745, soon after Pope died (fifth image). The grotto is still there, and you can tour it, provided you get there on one of the few days of the year when it is open to the public. A modern photo above shows a view down the length of the grotto, an updated and grittier version of the 1745 engraving (sixth image). Another photo shows a detail of some of the built-in minerals, many of which presumably came from Cornwall, the gift of William Borlase (seventh image).

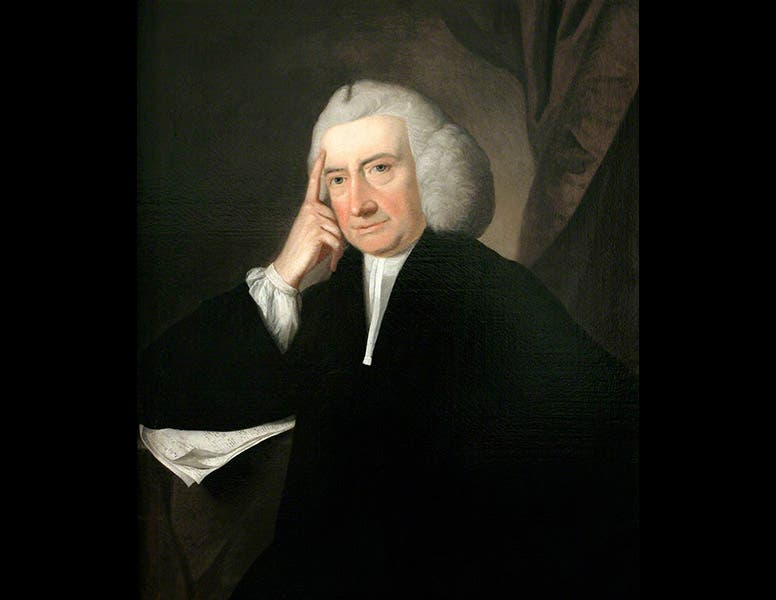

His portrait hangs in the Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro (second image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)