Scientist of the Day - William Beaumont

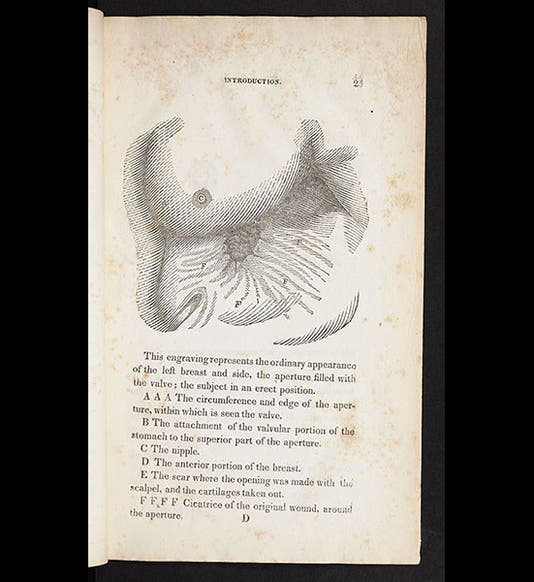

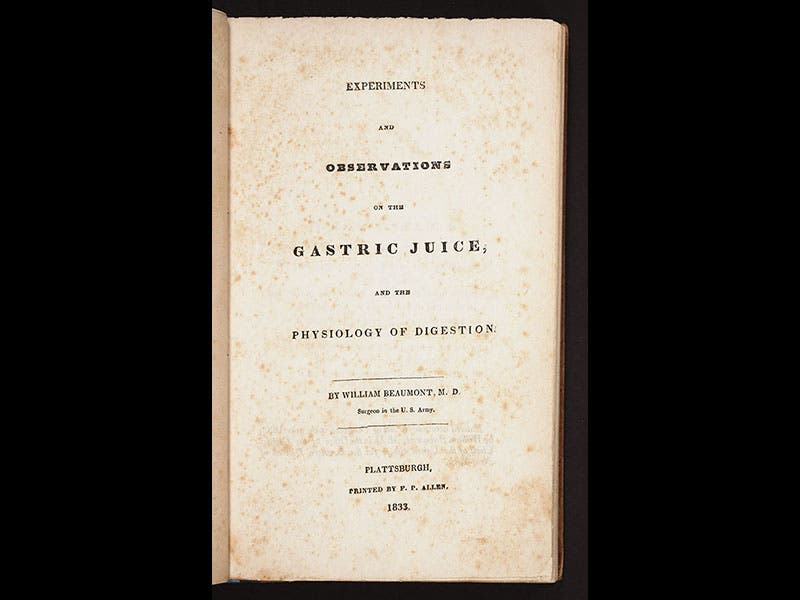

William Beaumont, a U.S. Army physician, was born Nov. 21, 1785. We celebrate today, not Beaumont's birthday, but an event that would change Beaumont's life and establish his medical reputation, one that is still going strong. Beaumont was stationed at Fort Mackinac in upper Michigan when, on June 6, 1822, he was called to treat a young voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, who had been accidentally shot in the stomach by a shotgun at close range. Since much of his left side was blown open, no one expected St. Martin to live, but Beaumont kept cleaning out the wound and gradually nursed his patient back to health, although it took several years. However, the wound did not heal completely; when St. Martin recovered, he had a fistula in his side, covered by a flap of skin that led directly into his stomach. Over the course of the next eight years, Beaumont did experiments on St. Martin to unravel the secrets of digestion, which at that time was rather a mystery. By inserting bits of beef on a string into St. Martin’s fistula, Beaumont determined that the stomach does not concoct, or grind, or melt its contents; instead, food is dissolved by an acid that resembles hydrochloric acid. Moreover, the acid is secreted in proportion to the food ingested, and this secretion is hindered by alcohol, and by anger (St. Martin apparently could grow quite testy when subjected to Beaumont’s gastronomic indignities).

In 1833, Beaumont published Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, a true classic in physiology. The book describes 62 different experiments that Beaumont performed courtesy of St. Martin’s fistula, and it concluded with a list of 51 inferences, such as “21. That the agent of chymification is the Gastric Juice … 24. That it contains free Muriatic [!hydrochloric!] Acid and some other active chemical principles.”

St. Martin and Beaumont parted ways in 1834, and for the next twenty years, Beaumont tried every inducement he could think of to get St. Martin back for further experimentation, but the Canadian would have nothing more to do with Beaumont. Beaumont died in 1853, but St. Martin, amazingly, lived to be 86 years old, his hidden window on the microcosm notwithstanding. When St. Martin died in 1880, the soon-to-be-famous physician William Osler begged to get the body for autopsy, but the family had had quite enough of the medical profession. They let St. Martin's body molder until it was of no use for dissection, and then buried his body in a secret grave.

We have a copy of Beaumont's Experiments and Observations in our History of Science Collection (second image); for a long time, it was the only book in the Library printed in Plattsburgh, New York, but then an Air Force document and a recent book on penguins spoiled that singularity. There are three illustrations in Beaumont’s book, woodcuts that show different views of St. Martin’s fistula; it is probably the most reproduced fistula in the history of medicine. We see two of the woodcuts above (first and third images).

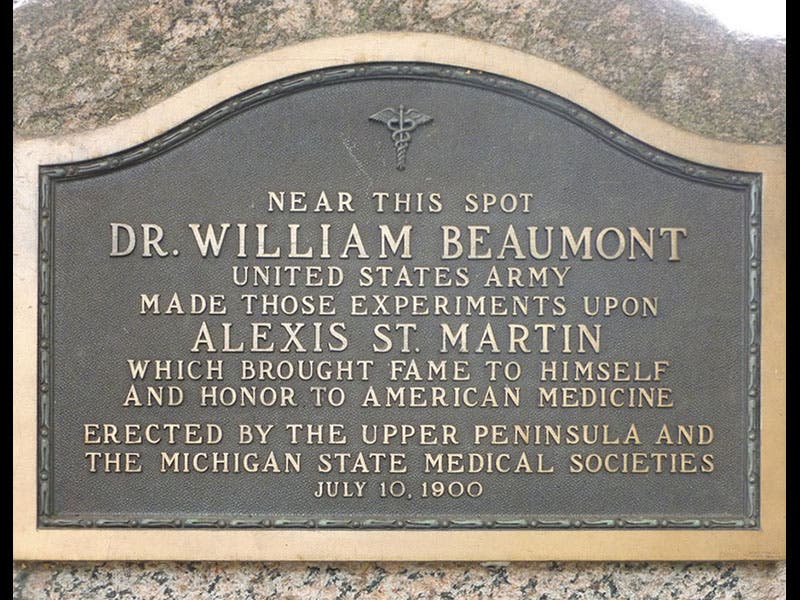

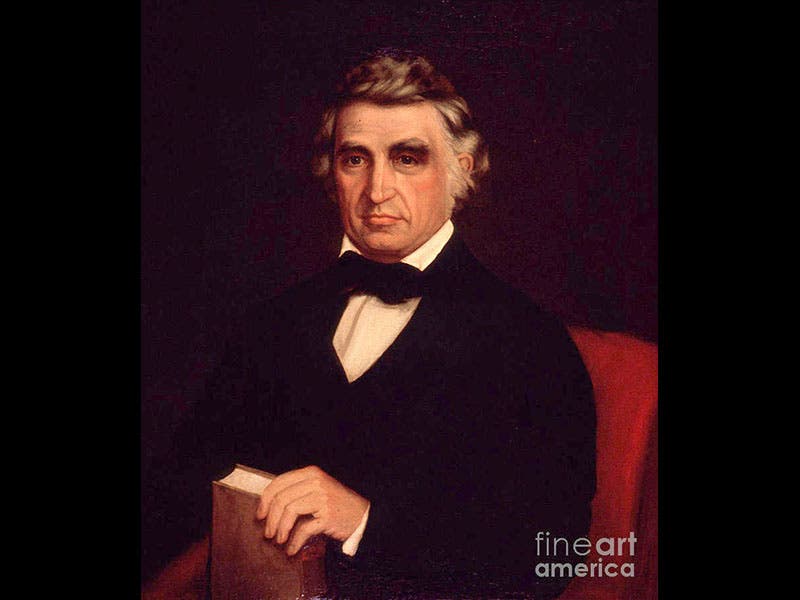

In 1900, a plaque was erected in honor of the Beaumont/St. Martin collaboration at Fort Mackinac, Mackinac Island, Michigan. We see it from a short distance away (fourth image) and from close-up (fifth image). The portrait of Beaumont is a posthumous one but a very good likeness (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.