Scientist of the Day - William Bateson

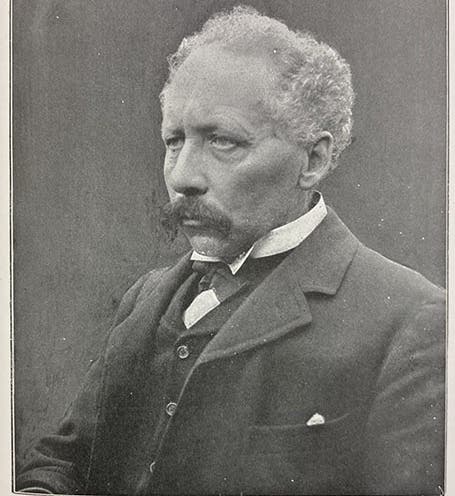

William Bateson, an English geneticist, died Feb. 8, 1926, at the age of 64. Bateson taught at the University of Cambridge for ten years, and then became director of a horticultural institution in Surrey, which gave him more room to conduct his plant and animal breeding experiments. Bateson had been doing breeding experiments for some time when, in 1900, Gregor Mendel's two papers of 1865 on heredity were rediscovered simultaneously by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns. Mendel's conclusions were controversial in the years following 1900, with many biologists opposing Mendelism. Bateson, however, was a champion of Mendel from the beginning, and he became involved in some very bitter exchanges with biologists such as Walter Weldon and Karl Pearson, who thought inheritance was much more complicated than Mendel had made it. There are several recent books that delve into the antagonism that arose between Bateson on the one hand and Weldon and Pearson on the other – three men who were once the best of friends and ended up as archenemies. The books are In the Pursuit of the Gene: From Darwin to DNA, by James Schwartz (2008) and Disputed Inheritance: The Battle over Mendel and the Future of Biology, by Gregory Radick (2023). Neither book is for the faint of heart, but they both provide chilling insights into how all-consuming academic controversy can become.

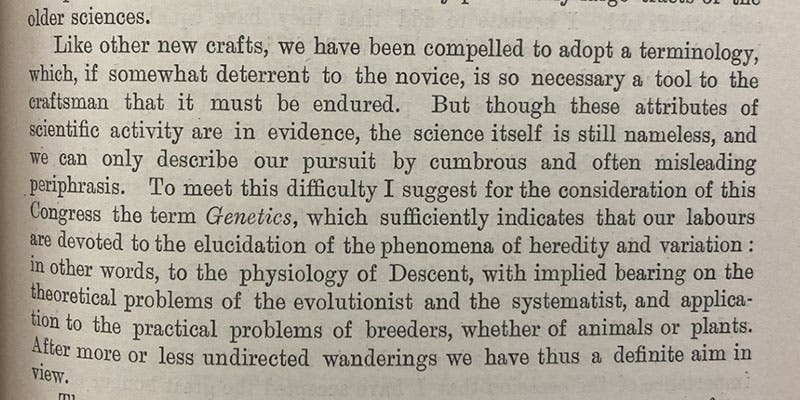

But let's turn to a happier, if much more trivial subject. I identified Bateson as a geneticist, and it was satisfying to do so, because Bateson coined the word: genetics. He did so in 1905, in a letter to a colleague, and then publicly in 1906, when he gave the opening address to the Third International Conference on Hybridisation and Plant Breeding in London in 1906. I had seen this stated a dozen times in as many potted biographies, but I had never seen the evidence. One of the strengths of a Library such as ours is that we are rich in conference proceedings. Many of these came to us when we acquired the Library of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1946, and many more when we added the Engineering Societies Libraries in 1995. So I looked up the International Conferences on Plant Hybridisation and found the proceedings for the third meeting in 1906. Sure enough, there was Bateson's address – he was president of the Conference – and here is the relevant paragraph of his address (second image), from which we extract this statement:

“To meet this difficulty [lack of a name for our science], I suggest for the consideration of this Congress the term genetics, which sufficiently indicates that our labours are devoted to the elucidation of the phenomena of heredity and variation…”

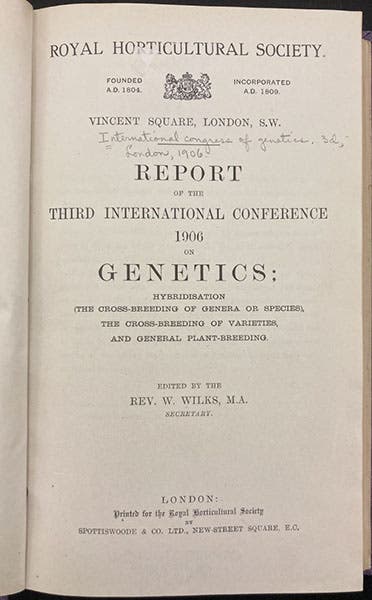

The word "genetics" is printed in Italics, making it easy to spot on the page. Bateson’s suggestion was immediately taken up by others. The conference was officially called, at the time it met in 1906, the Third International Conference on Hybridisation and Plant Breeding. But by the time the proceedings were published, in 1907, it had become: The Third International Conference on Genetics, as we can see from the title page of the volume (third image). And it is interesting to note that it would be another three years before Wilhelm Johannsen proposed that the unit of inheritance should be called the gene. We have written a post on Johannsen. I don’t know who chose a portrait of Mendel for the frontispiece to the entire proceedings, but I would guess it was Bateson, and since it is such as nice portrait, and well printed, I include it here (fourth image)

As I am sure everyone realizes, the invention of words does not rank very high in the pantheon of creative acts. When a new science emerges, someone has to come up with a word for it, and it is usually not the result of a profound intellectual experience. Such word-smithing should not command our notice or admiration, unless someone is really very good at it, and coins multiple words that have entered the lexicon of science, as with William Whewell, who invented the word scientist itself, and many other useful word-labels (see our post on Whewell). But the fact is, we do like to know who first coined words that we now use regularly, and there is nothing wrong with acclaiming Bateson as the man who invented the word genetics. And I figure that if we are going to do so, we can at least look up the first appearance in print, and make it available to everyone in its original form. So that’s what I have done, for what it is worth.

In our post on Johannsen, I showed a photo taken when Johannsen visited Bateson at his home in Surrey in 1923. It is such a nice photo – Mr. Gene and Mr. Genetics – that I include it again here (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.