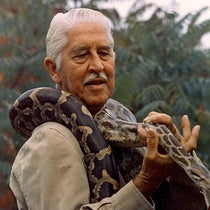

Scientist of the Day - William Bartram

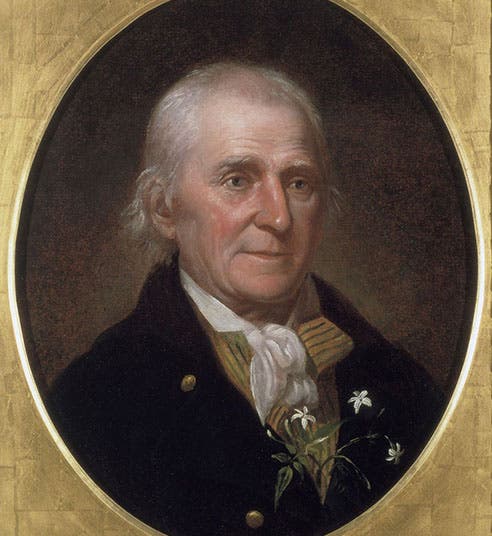

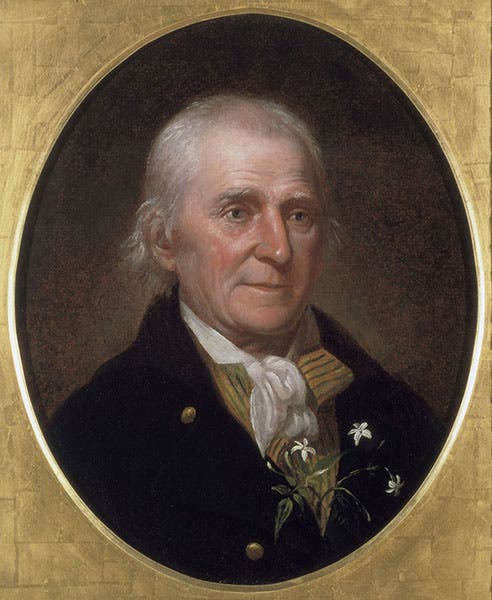

Portrait of William Bartram, oil on canvas, by Charles Willson Peale, 1808, Independence National Historical Park, Second Bank, Philadelphia (https://www.nps.gov/inde/)

William Bartram, an American explorer and naturalist, was born Apr. 20, 1739, in Kingsessing, Penn., just west of Philadelphia. William was the son of the first great American-born naturalist, John Bartram, whose birth we celebrated in a post less than a month ago, on Mar. 23, 2023. William was interested in natural history from his earliest days, which one might attribute to being a child of John, except that none of William's siblings had that passion to such a degree. Unfortunately, William had few other interests, to the despair of his father, who thought that William needed to have a livelihood other than traipsing through the countryside. But William really never did, and he would ultimately rely on patrons, such as Peter Collinson and John Fothergill, Quaker merchants in London, to underwrite his collecting expeditions.

William was also a gifted artist, a skill his father lacked, and much of his repayment to his patrons was in the form of drawings and watercolors. The Fothergill Album at the Natural History Museum in London, which we discussed in a recent post on Fothergill, consists entirely of William's paintings and drawings.

William made his first extended collecting expedition in 1765, when he accompanied his father to the Carolinas and Georgia. On this occasion, they discovered the now famous Franklin tree, Franklinia alatamaha, which is now extinct in the wild. We showed a colored engraving of the Franklin tree by Redouté in the Fothergill post. By this time, John had founded Bartram’s Garden at Kingsessing, and that became the seedling ground for all future Franklin trees, after it disappeared from its natural habitat.

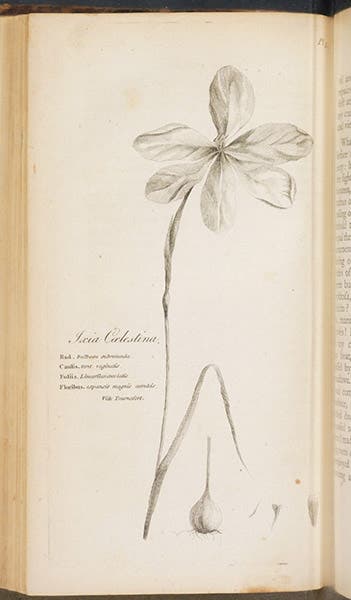

As father John concerned himself more and more with his Garden, William longed to travel again. After some foundering about, William planned a return expedition to the South, to Florida, which would eventually include Georgia and Alabama. During this extended trip, from 1773 to 1777, he collected and drew hundreds of new species, plant and animal, such as the soft-shelled tortoise (third image), Bartram's ixia (a blue iris, fourth image), and the oak-leaf hydrangea (fifth image), all of which he would picture in his published narrative of his travels. He also had adventure after adventure, as when he encountered the king of all alligators in a sinkhole in Florida.

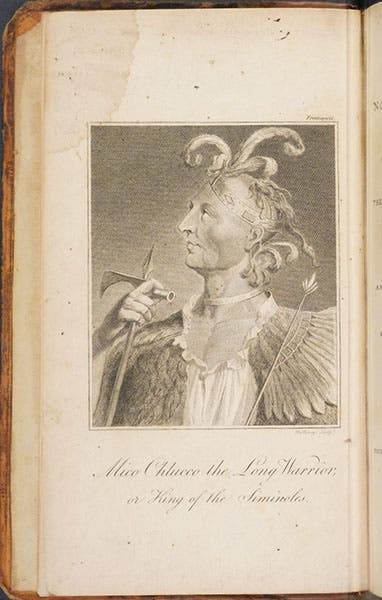

Bartram spent much of the 1780s writing his expedition narrative, and it was finally published in 1791 in Philadelphia, as Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida (second image). We have the first London edition (1792) in our collections. The book soon became an American natural history classic, with its vivid descriptions and exuberant prose. It also contains some of the first sympathetic accounts of Native American tribes of the southeast, such as the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole. William did not at all care for the way the Indians were treated by the merchants who ran the trading stores in Florida and was not shy about saying so. He was also highly critical of the view, espoused by the French naturalist Georges Buffon, that the inhabitants of the New World, animals and peoples, were inferior to those of the Old World. William had an ally here in Thomas Jefferson. The frontispiece of Bartram’s Travels (sixth image) depicts Mico Chlucco, King of the Seminoles, whom Bartram met first in 1765 and then again, in a more extended fashion, on his expedition to Florida. Mico Chlucco gave William the nickname, “Puc-Puggy,” the Flower Hunter, which William rather liked.

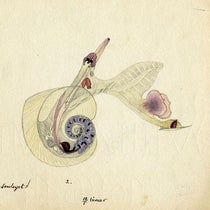

Bartram’s Travels contains only six uncolored line engravings, plus a map of east Florida and the frontispiece, and none of the illustrations really show how good an artist Bartram was. The drawings and watercolors he sent to Fothergill, Collinson, George Edwards, and others, provide much better evidence of his skill and creativity. We showed two of these in our post on Fothergill, a watercolor of the Franklin tree and an ink drawing of a sandhill crane. We show here another here, of a Thalia plant and a green heron (seventh image, just below).

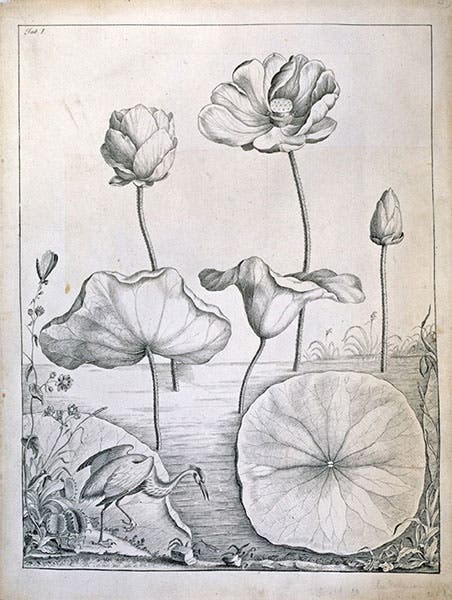

The drawings by William that I like best are his whimsical compositions, where he puts together plants, birds, insects, and reptiles, often at different scales, just for fun. Most of these are in the Natural History Museum in London, and I have chosen for this space a drawing of giant American lotuses in various states of flowering, a tiny blue heron, and some hungry Venus fly-traps, which Bartram finished in 1767 and sent to John Collinson, who was unable to tell whether it was an engraving or an ink drawing, so finely was it executed (eighth image).

After the Travels was published and William became better known to the public, he seemed to retreat from his new-found fame. He moved in with his brother, John Jr., and helped out with the Garden, and when John died, he continued to live with John's daughter and her husband. William was elected to a professorship at the University of Pennsylvania but never taught there. He was offered a post on a western expedition by Thomas Jefferson but turned it down. He was painted in 1808 by Charles Willson Peale, a wonderful portrait that you can see in the Independence National Historical Park in Philadlphia, at the Second Bank site (first image). William died on July 22, 1823, and was buried at Bartram’s Garden. I was unable to locate a grave marker, if one exists.

Scholarship on William Bartram is not lacking and can be a little overwhelming; we recommend a book that belies its coffee-table size with an excellent account of Bartram’s life and Travels and an abundance of illustrations from the Natural History Museum: The Art and Science of William Bartram, by Judith Magee (Natural History Museum, 2007).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.