Scientist of the Day - William A. Fowler

William A. "Willy" Fowler, an American astrophysicist, was born Aug. 9, 1911. Fowler taught at Caltech in Pasadena, where he pioneered a new discipline, experimental nuclear astrophysics. Working at the Kellogg Lab at Caltech, he accelerated protons and smashed them into atoms, trying to find out what nuclear reactions are possible and what kind of energies they yield, in the hope of applying such knowledge to learn how the stars produce energy. He first came to prominence when he figured out the nuclear process that powers the Sun. Hans Bethe in 1939 had demonstrated that the Sun must get its energy from the fusion of hydrogen into helium, but there were two possible paths for such a nuclear reaction: the carbon cycle, where a carbon atom absorbs four hydrogen atoms in sequence and then spits out a helium atom, or the proton-proton process, where a hydrogen atom fuses with three other hydrogen atoms in succession to create a helium atom. Both were theoretically possible, and Bethe was unable to choose between them. In the early 1950s, Fowler showed that the carbon cycle could only occur in stars bigger and hotter than the Sun, and that the Sun must derive energy from the proton-proton process.

In 1952, Fowler spent a semester at Cambridge in England, where he met two young astrophysicists, Geoffrey and Margaret Burbidge, who had discovered some unexpected elements in surprising quantities in certain stars. Fowler set about trying to explain how such elements came to be in stars. While in Cambridge, he also met Fred Hoyle, who four years earlier had declared his opposition to the Big Bang theory proposed by George Gamow and others. Gamow thought that all the elements were synthesized in the Big Bang, and since Hoyle was a Big Bang denier, he had to find some other way to make elements, and he thought the solution lay in the crucibles of stellar interiors. However, he ran up against a seemingly insurmountable problem: he could show how two helium atoms could fuse to become a beryllium atom, but adding another helium atom to make carbon seemed an impossible occurrence, unless the carbon atom existed in an energy state that had never been observed.

In 1953, Hoyle came to Pasadena, and he convinced Fowler's lab to search for this mysterious energy state of carbon, which he believed existed, because otherwise there would be no carbon in the universe, and therefore no us. He invoked what we now call the anthropic principle: we exist, so therefore this energy state of carbon must exist. Intrigued, Fowler agreed to do the necessary experiments, and lo and behold, the previously unnoticed energy state of carbon was detected.

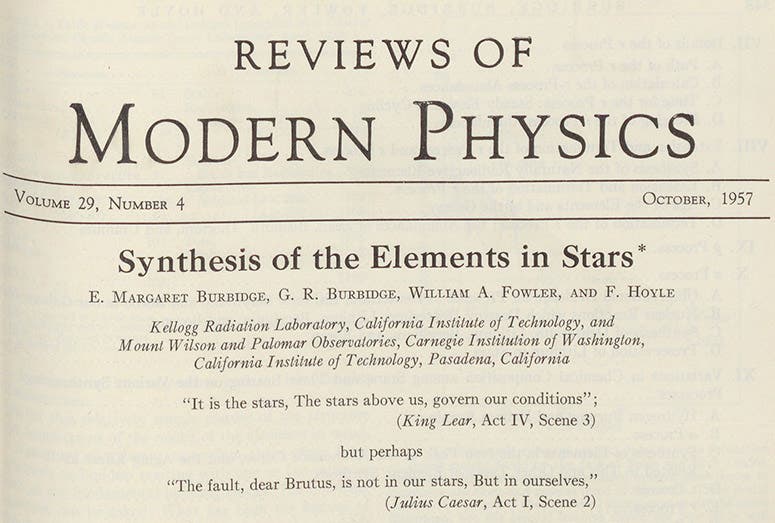

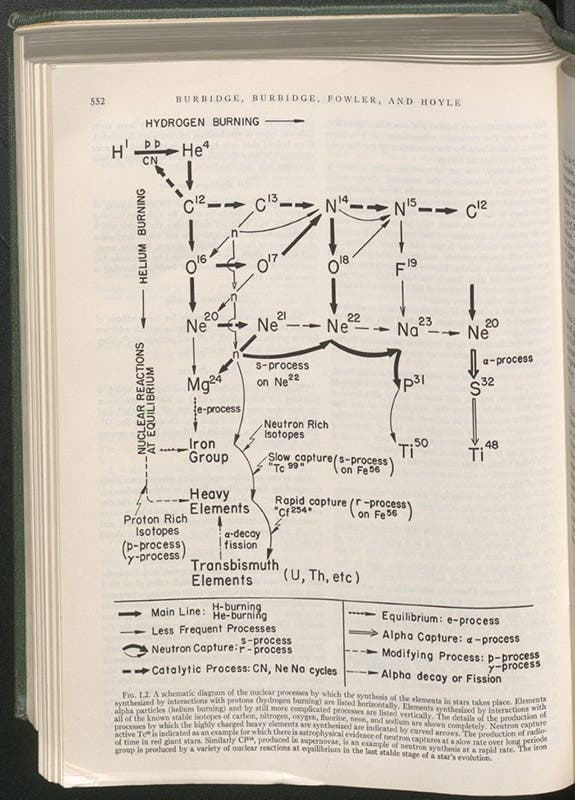

Fowler, Hoyle, and the Burbidges continued to collaborate, and in 1957, they published a paper called "Synthesis of the elements in stars." In this paper, they showed how the conditions existing in giant stars were conducive to building up elements by the fusion of hydrogen into helium, helium into carbon, carbon into oxygen, and, when giant stars exploded, even the heaviest elements. They identified seven fusion reactions that could produce all of the elements except a few of the lightest, such as helium, deuterium, and lithium.

This paper is one of the milestone publications in 20th-century science, the equivalent in astrophysics of the Watson-Crick paper in molecular biology of 1953. It is so famous that it is routinely referred to as B2FH (pronounced "B squared FH"), an acronym using the first letters of the four authors’ last names (which by the way, were in alphabetical order, although Hoyle and Fowler were the lead authors). We show here a detail of the first page of B2FH (second image), with several puckish quotations from Shakespeare added by Hoyle, and a remarkable graphic that summarizes all of the possible nuclear reactions that create elements in stars under a variety of condition and temperatures (third image).

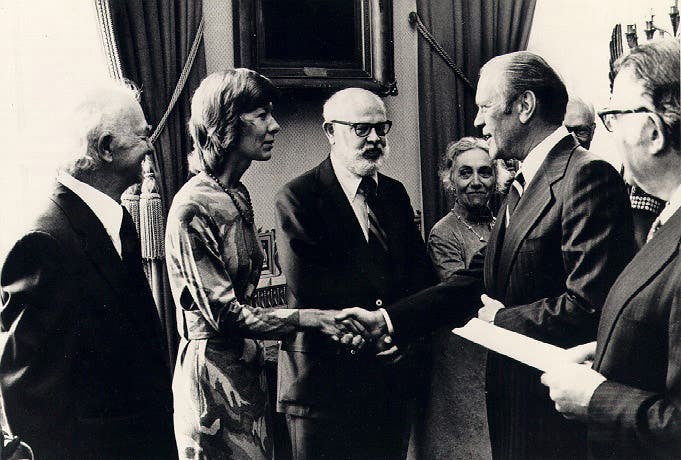

Fowler received the National Medal of Science in 1975 for his work (his Caltech colleague Linus Pauling received his own Medal that same year), and a White House publicity photo commemorates the occasion (fourth image).

In 1983, Fowler shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on stellar nucleosynthesis, as his field is called. But the person with whom he shared the Prize with was not Fred Hoyle, but rather an Indian-American physicist named Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. Why Hoyle was not included is a mystery to this day. It may stem from Hoyle's reluctance to accept the Big Bang, or from his continuing iconoclasm on all sorts of issues, or from his vocal objections to some of the Nobel Prize committee’s actions in the past. He was definitely not one of the Good Old Boys of his field. I discussed some of the possibilities in a post on Hoyle last year.

Whatever the reason for Hoyle’s exclusion, we can't blame Willy Fowler. He certainly earned his half of the Prize. And in the biographical notice he wrote for the Nobel award, he gave Hoyle full credit for coming up with the idea of stellar nucleosynthesis, and for being the second greatest influence on his professional life, after Hans Bethe (who did get a Nobel Prize for his work). You can almost hear the question that Fowler could not ask: why isn't Fred Hoyle sharing this award with me? I am sure that Fowler wished it were a three-way affair.

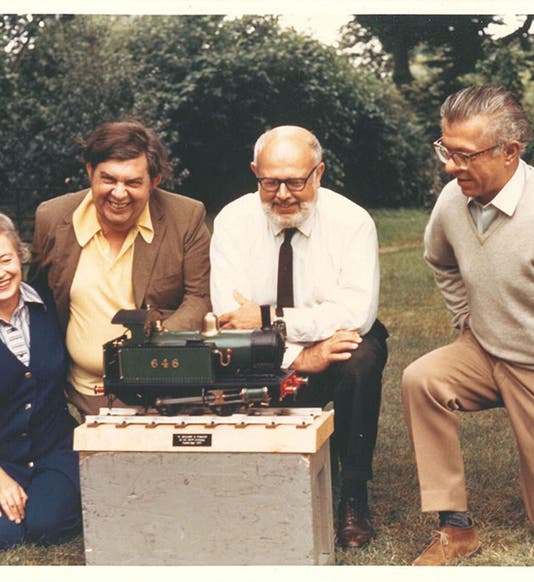

Fowler was a lifelong steam-locomotive buff, which explains the birthday gift in our first image. I am sure it is not a coincidence that the four participants at the party are lined up in the order: BBFG.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.