Scientist of the Day - Wilhelm Röntgen

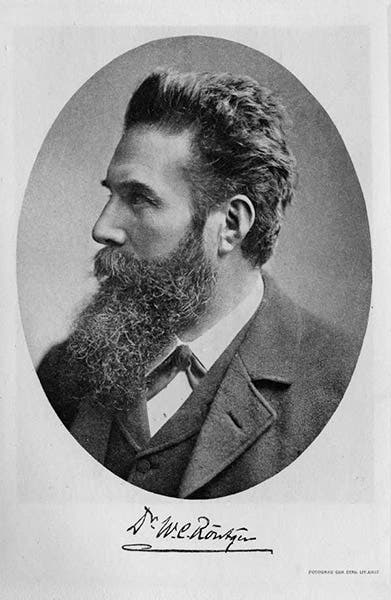

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was a fifty-year-old professor of physics at Würzburg University when he made a discovery that would utterly transform the nature of physics over the next 30 years. On this day, Nov. 8, 1895, Röntgen discovered X-rays. He had been doing experiments with cathode-ray tubes, like the Crookes tube, and on this occasion, he had covered the tube with a light-proof cardboard shroud. Working in the pitch dark, he happened to notice a gleam from a nearby laboratory bench when he turned the apparatus on. Investigating, he found the gleam came from a fluorescent screen, even though there was no visible light to cause the fluorescence. He soon found that some kind of invisible ray was able to go right through the black cardboard. He called these rays “X-Strahlen” – X-rays – and spent the next six weeks investigating their properties. On Dec. 22, he took a photograph of his wife’s hand, revealing the bones within. We showed this photograph in our first post on Röntgen, some 8 years ago, on his birthday.

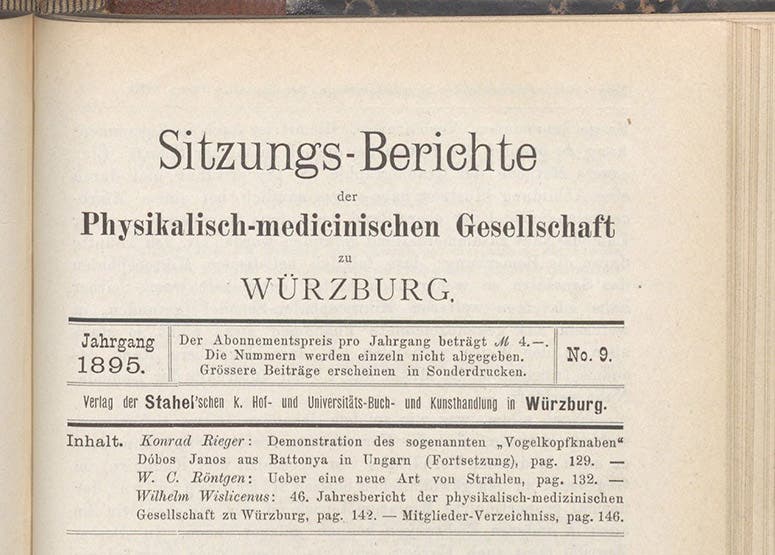

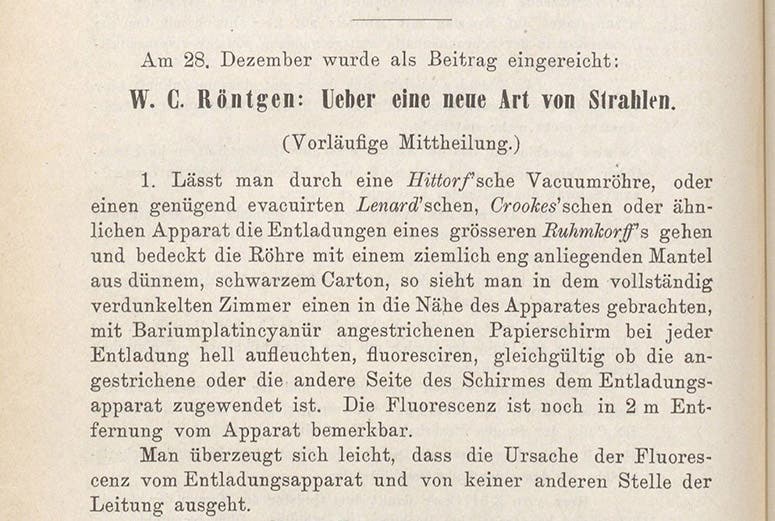

Since we have told the story once before, I thought on this occasion I would show how Rontgen announced his discovery to the scientific world. His X-ray photos of hands are often reproduced, but his publications, almost never. He read his first paper to the Physical-Medical Society of Würzburg on Dec. 28, 1895, and it was published almost immediately in their Sitzungs-Berichte (Proceedings) in the last issue of the year. The paper was called “Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen” (“On a new kind of radiation”). We see here the first page of the issue (third image), announcing Röntgen’s paper (on p. 132) and then the beginning of the paper itself (fourth image).

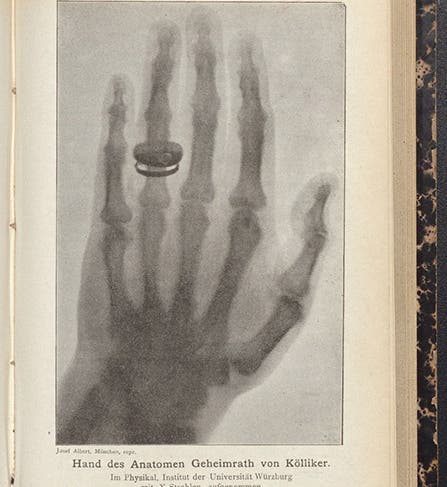

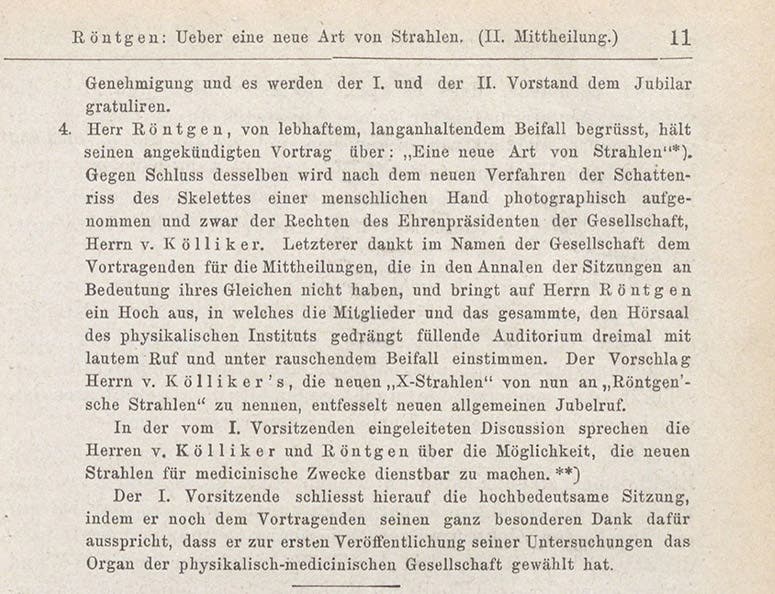

Turning the pages (issue 1 of 1896 follows immediately after issue 9 of 1895), we soon encounter an X-ray photograph of a hand, not that of his wife (first image). A few pages later there is an explanation (fifth image), which tells us that at the session of Jan. 23, 1896, presided over by chairman Albert von Kölliker, Röntgen, in front of everyone, took an X-ray photograph of von Kölliker’s hand, and that was the photograph bound into the issue. Von Kölliker was so impressed that he immediately suggested that the new rays should not be called X-rays, as Röntgen termed them, but rather Röntgen rays, which brought forth allgemeinen Jubelruf (general cheering) from the audience.

Description of the session of the Würzburg Society on Jan. 23, 1896, when Röntgen took an X-ray photograph of the hand of the session chaiman, Albert von Kölliker, and von Kölliker named the new rays, “Röntgen rays”, Sitzungs-Berichte der Physikalisch-medicinischen Gesellschaft zu Würzburg, 1896, no. 1, p. 11 (Linda Hall Library)

The discovery of X-rays was so momentous because it led immediately to the discovery of radioactivity, sub-atomic particles such as electrons and alpha particles, and gamma radiation. Atomic physics was born at that moment and would rapidly mature. For his discovery, Röntgen was awarded the very first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. Shy by nature, he declined to give a Nobel address.

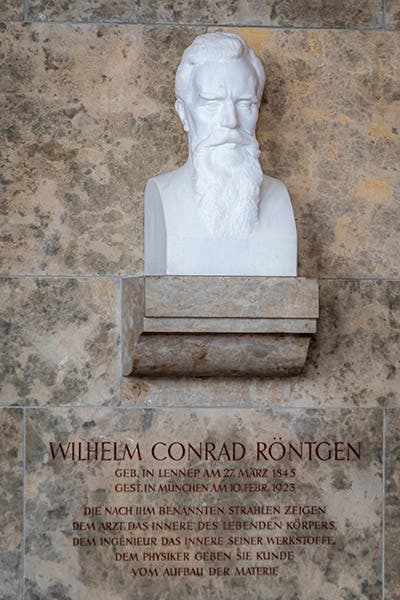

In our first post on Röntgen, we showed a portrait, a cropped version of von Kölliker’s X-rayed hand and a small version of his wife’s X-rayed hand, an old photo of his laboratory, and a recent shot of his well-maintained grave. Here we show a different portrait, an uncropped view of von Kölliker’s X-ray, just as it was published in the Sitzungs-Berichte, three other details from his published papers, and a bust of Röntgen in Munich. In Würzburg, they have turned part of the old Physics Institute into a Röntgen memorial; from photographs (seventh image), it looks as though it might be worth visiting. And there is now available a different version of the X-ray photo of Anna Bertha Ludwig’s (Röntgen’s wife’s) hand, this one with a pedigree – it was given by Röntgen to Professor Ludwig Zehnder of the Physik Institut, University of Freiburg, on Jan. 1, 1896. So we tack in on at the end, since it is much better than the one we used earlier (eighth image, below).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.