Scientist of the Day - Wilhelm Johannsen

Wilhelm Johannsen, a Danish botanist and geneticist, died Nov. 11, 1927, at age 70. In 1900, the work of Gregor Mendel was rediscovered, independently, by three researchers, and almost immediately there was interest in merging Darwinian natural selection and Mendelian genetics. The general belief among Darwinians was that natural selection could modify organisms indefinitely. Johannsen was an early convert to Mendel, but he wondered about the malleability of organisms under the pressure of natural selection. From 1900 to 1902, Johannsen did a series of breeding experiments on the Princess bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, carefully recording the weights of the beans and their statistical distribution. He began with a "pure line" of beans that were as genetically identical as he could breed then, and he discovered that even when you selected the largest beans and planted those, you could get only so far from the mean, and no further. Natural selection did not create variations; it had to wait for them to appear.

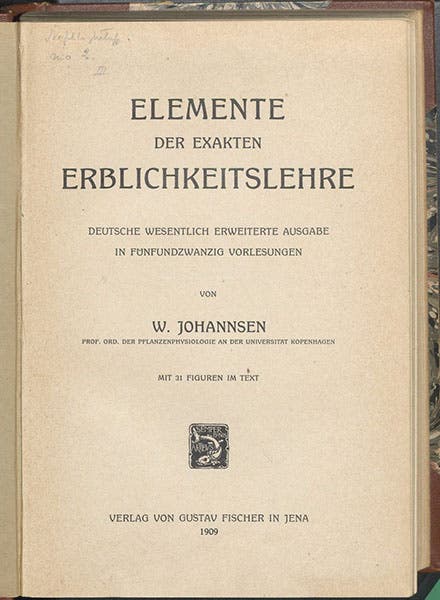

Johannsen also noticed that when you sort the beans by the attributes of their parents, there was no way of predicting the traits of the next generation. The appearance of the bean plant is not the same thing as its genetic structure. By 1909, he had sorted this all out, and he published Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre (Elements of an Exact Theory of Heredity), where he distinguished between the physical appearance of an organism, which he called phenotype, and its genetic structure, which he called genotype. A similarity in phenotypes does not necessarily indicate a similarity in genotypes. Not only did Johannsen distinguish between phenotype and genotype, he also coined one more word to describe a single genetic element: the gene. Mendel had used the word factor in his seminal papers of 1865, and some had substituted a Darwinian term, pangene, but, as Johannsen argued, the term gene is simple, and without connotations, and he was right – it has been gene ever since.

The surprising thing about Johannsen is that he is so little known, compared to Mendel, Hugo de Vries, and Thomas Hunt Morgan, even though scholars acknowledge that his work was essential in bridging the gap between de Vries work on mutations in primroses and Morgan’s experiments with fruit flies. I own half-a-dozen books that claim to be histories of genetics between Mendel and Watson-Crick, and none of them give Johannsen much more than a page, if they mention him at all; too often he is cited only for inventing the word "gene," which is the least important thing he ever did.

On the other hand, the Library owns a book called: Rebels, Mavericks, and Heretics in Biology (2008), and there is an entire chapter on Johannsen, as if he were some kind of outcast. That is just wrong! As Raphael Falk, the author of the article (which is excellent), noted at the outset, there were four major advances that shaped genetics from 1860 to 2010: the discovery of paired factors that determine characters; the realization that physical appearance and inheritable traits are two different things; the demonstration that genes are found on chromosomes; and the discovery that chromosomes are arranged in the structure of a double helix. The first was the work of Mendel, the third that of Morgan, and the fourth, Watson and Crick. The second, a major advance, was the work of Wilhelm Johannsen, and he well belongs in a pantheon with the other three.

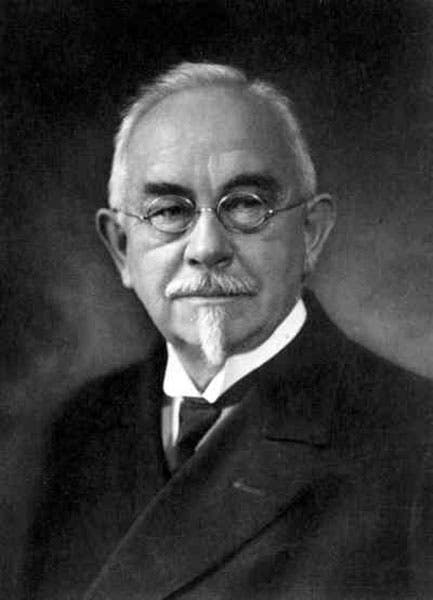

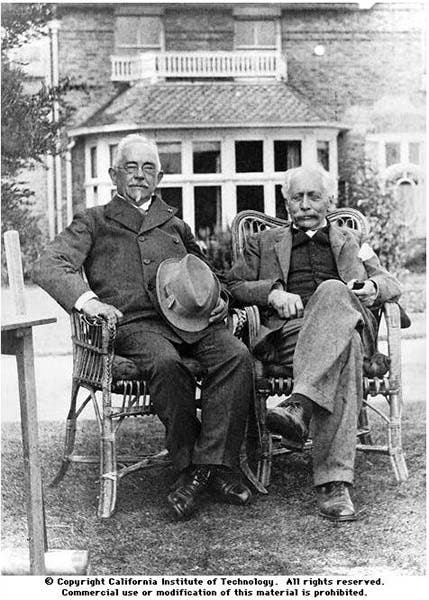

I could not find a photograph of Johannsen when he was 52 years old and about to announce the phenotype-genotype distinction. There were however many photographs taken in the 1920s, so he clearly had considerable peer approval by then, and I show three of those. The only statue or bust I could locate is outside the Botanical Laboratory in Copenhagen, where he worked, which would not, in my opinion, be irrevocably harmed by a cleaning.

I took photographs of the three pages in Johannsen’s book of 1909 where he introduced and explained his use of the terms: gene (p. 124), phenotype (p. 123), and genotype (p. 130), and I was going to show them all, but I decided one page of botanical German was probably enough for most people, so I just show a detail of the “phenotype” page (third image). If anyone wants to see the "gene" page and the "genotype" page, I would be happy to send them along.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.