Scientist of the Day - Wilhelm Homberg

Wilhelm Homberg, a Dutch/German/French chemist, was born on Jan. 8, 1653, in Batavia (modern Jakarta), where his father served in the Dutch East India Company. Homberg’s family moved back to Amsterdam (his mother was Dutch) when Wilhelm was in his teens, and Wilhelm went on to Leipzig and Jena, where he studied law. He practiced law for a while in Magdeburg, where he met Otto von Guericke, then in his seventies, who had invented an air pump in the 1650s and performed the famous demonstration of the Magdeburg spheres, which confirmed the hypothesis that the atmosphere has weight. It is thought that von Guericke turned Homberg’s interests from law to natural philosophy.

Homberg spent the next 15 years travelling, to Italy and through Germany, expanding his interests, which now included alchemy and chymistry, to use the word now applied to early modern chemistry. In Italy he was introduced to the “Bologna stone,” a salt of barium which could be made phosphorescent by calcination (see our post on Fortunio Liceti for more on the Bologna stone), and Homberg became something of an expert on phosphorescence, even discovering some phosphorescent compounds of his own. He visited England in the late 1670s and met Robert Boyle, carrying a letter of introduction, it is said, from Gottfried Leibniz. In 1682, Homberg visited France, where he met members of the Académie des Sciences and apparently was well received there. He took French citizenship, travelled a bit more, and then settled down in France somewhere around 1687, where he would spend the rest of his life. He was invited into the Académie in 1691, where he eventually became director of their chemical laboratory.

The science of chymistry was in an interesting state in the period from 1680 to 1715. It was becoming rigorously experimental, with increasing interest in quantification, and in the search for new reactions, and possibly new elements. But the old alchemical interest in chrysopoeia, the attempt to turn base metals into precious ones, especially gold, still attracted the interest and investigations of chymists, as did the search for the philosopher’s stone, and a universal alkahest, or solvent. Homberg spent much of his chemical career working on chrysopoetic experiments, without success, or should we say, with negative results. He was fortunate to have the support of Philippe II, duc d’Orléans, who took in Homberg as a tutor and built a superb chemical laboratory for Homberg and himself, one of the finest in Europe, in the Palais Royale.

Homberg served the Academy and the Duke for the next ten years (Philippe fell from grace in 1713, when he was suspected, unfairly, of poisoning the dauphin, the heir of Louis XIV, and his family; Homberg was suspected briefly of having supplied the poison). Homberg published many papers in the Memoires of the Academy, and welcomed visitors and travelers to the Duke’s lab. He trained important young chemists, such as Étienne-François Geoffroy. When Homberg died in 1715, at the age of 62, the secretary of the Academy, Bernard de Fontenelle, wrote and delivered a stirring Éloge of Homberg (as he did for many deceased academicians), although his biographical account is apparently filled with errors. Still, it was a heartfelt tribute to a man Fontenelle thought worthy of commemoration.

When I studied early modern chemistry (not yet referred to as “chymistry”) in graduate school, we never learned about Homberg, perhaps because he didn’t’ discover anything earthshaking, except for the photosensitivity of silver salts (observed around 1693), and he never published a book (although a book manuscript had been completed at the time of his death in 1715). But a recent book by Lawrence Principe, The Transmutations of Chymistry: Wilhelm Homberg and the Academie Royale des Sciences (2020), has mined the archives of France and much of the rest of Europe to show us how influential Homberg was in effecting the transmutation of alchemy into chemistry in the early 18th century, in spite of, or perhaps because of, his interest in traditional alchemical problems. He brought to chymistry a new rigor and a new concern with standards, and a belief that chymistry was as important a science as astronomy or physics, even if it lacked a classical pedigree.

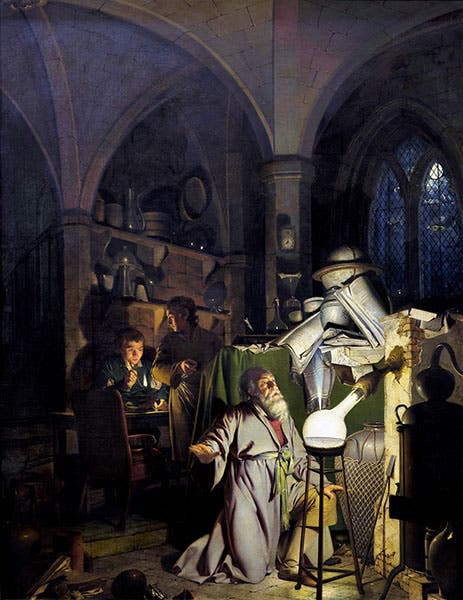

Principe chose for the dust jacket of his book a painting by Thomas Wyck in the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, painted sometime before Wyck’s death in 1677, and called An Alchemist in his Studio (first image). It was a good choice, for it shows a more academic alchemist than the traditional depiction of a scrabbler in a messy lab (as in many of Wyck’s other renderings of alchemists, such as this one in the Hermitage). It is interesting to compare Wyck’s alchemist with one painted almost a century later, by Joseph Wright: The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher's Stone, Discovers Phosphorus (second image), where the alchemist and his environs are much more traditional. Given Homberg’s interest in phosphorescence, one might initially suspect that this is a depiction of Homberg, but it cannot be, for everything else is all wrong, especially the beseeching of divine guidance. Thomas Wyck’s version was much closer to the mark, even if it was painted 30 or 40 years before Homberg transformed his own small corner of the chymical world.

Two portraits of Homberg were painted in his lifetime, by the French portraitists Hyacinth Rigaud and Pierre Gobert, Professor Principe tells us. Both portraits are lost, so we have no visual commemoration of Wilhelm Homberg. His legacy would perhaps have been stronger had one of them survived.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bivouac on Jan. 26 [1854], chromolithograph from a sketch by Balduin Möllhausen, Explorations and Surveys for a Railroad Route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean: Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, by Amiel W. Whipple (Pacific Railroad Report, 3), 1856 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/55140a90-4b5d-4dac-832c-5def5cb51a10/Whipple1_cover.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)