Scientist of the Day - Wilfrid Voynich

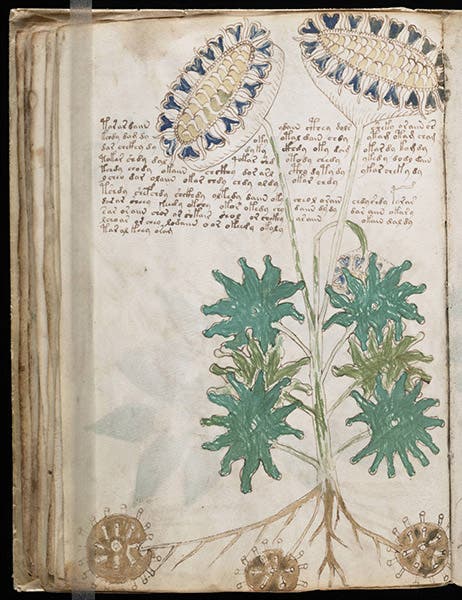

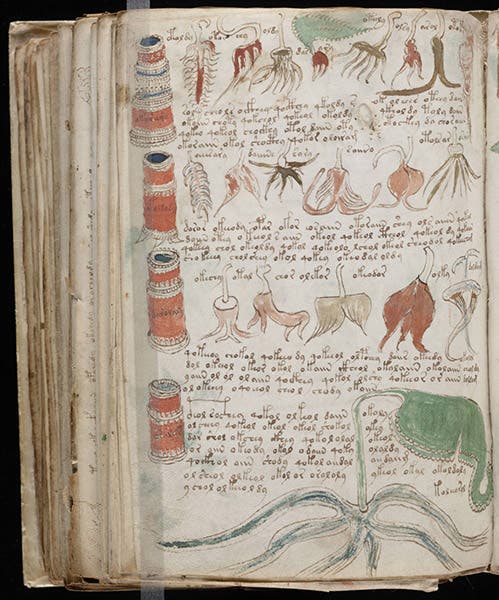

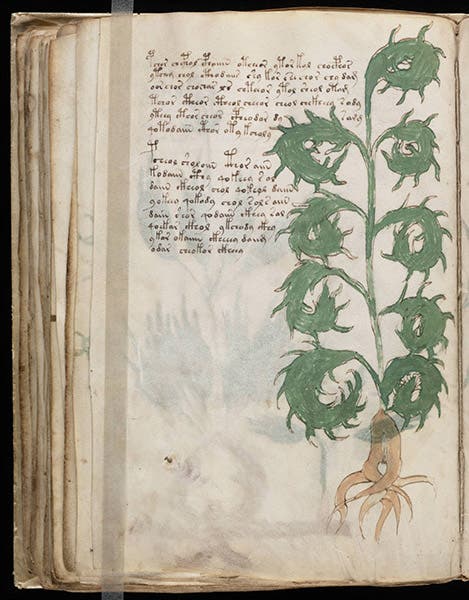

Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish antiquarian bookseller, was born Nov. 12, 1865. By no measure was Voynich a scientist, but by giving him that title for a day, we get a chance to discuss his tantalizing namesake, the Voynich manuscript. After living the young life of a radical Polish revolutionary, Voynich settled down to a career as a London book dealer, doing well enough that he could eventually open a New York City branch. In 1912, Voynich bought 30 manuscripts from a Jesuit library in Italy. One of these was distinctive, because it consisted of some 120 vellum leaves, many of them attractively illustrated with hand-painted images of plants, constellations, and other natural objects, but with a text written in an unknown language. It was the untranslatable script that intrigued Voynich. It seemed to be more European than Asian, and the manuscript had a letter folded into the front from Johannes Marcus Marci à Kronland, a 17th-century Bohemian physical scientist, addressed in 1665 to the great polymath Athanasius Kircher in Rome, presenting him the with the manuscript and suggesting that it had once belonged to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II. So the manuscript had, or seemed to have, an impressive pedigree.

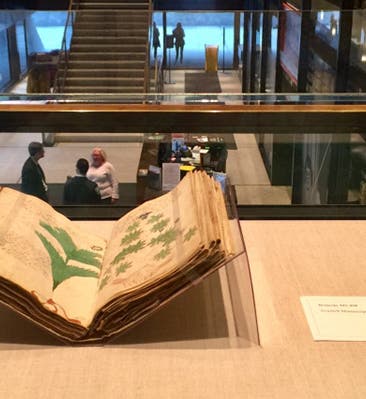

Voynich thought he had a work by the medieval alchemist Roger Bacon, written in some sort of cipher, but he could not interest anyone in trying to decipher it. When Voynich died in 1930, the manuscript passed to his widow; she bequeathed it on her death in 1960 to a friend, and the friend promptly sold it in 1961 to the noted New York book dealer H. P. Kraus (interestingly, at least to us, in 1961 we bought from Kraus our copy of Johann Bayer's Uranometria (1603), the linchpin of our future star atlas collection). Kraus was unable to sell the manuscript - he probably wanted a princely sum - and in 1969, he donated it to the Beinecke Library at Yale, where it still resides.

An amazing amount of attention has been paid to the Voynich manusciprt since it took up residence in New Haven. Ink and paper have been scrutinized by a variety of analytical techniques, with fairly consistent results; the vellum was produced in the first half of the 15th century, and the inks and paints are consistent with a 15th- or 16th-century production.

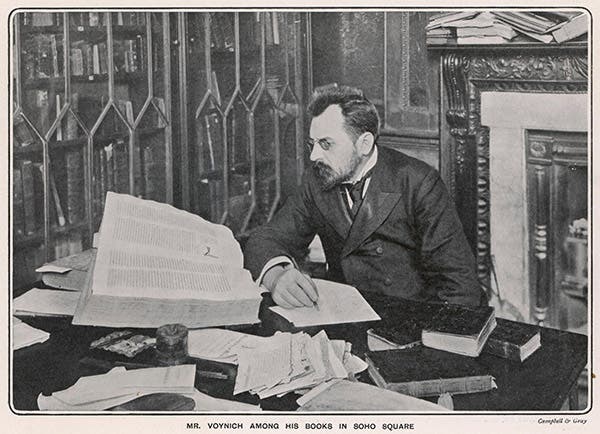

But the text has refused to yield up its secrets. Dozens of cryptologists with very sophisticated algorithms have tackled the script, with no success, or at least no generally acknowledged success. We do not know if Voynichese is an unknown language, a code, a cipher, or a hoax. We cannot even identify most of the images, not even the plants. So the Voynich manuscript remains a mystery, the most mysterious scientist manuscript in the world, in the opinion of many. If you would like to have a stab at solving the mystery, the Beinecke Library published a facsimile several years ago, which we have in our general collections. The entire manuscript is also available on Wikimedia Commons, from which we have drawn our three illustrated pages. The fifth image shows Voynich, our scientist for a day, at work in his London bookshop.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.