Scientist of the Day - Wilbur Wright

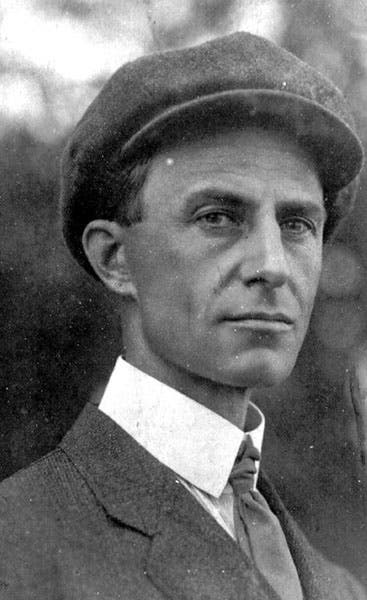

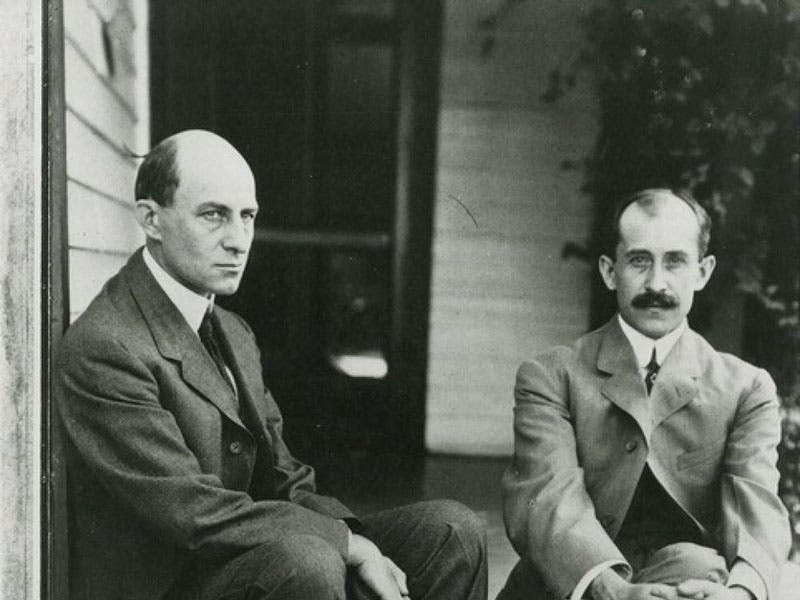

Wilbur Wright, the elder of the aviating brothers, died May 30, 1912, at age 45. Surprisingly, we have never featured either of the Wright brothers as a Scientist of the Day, although we have discussed nearly all the other early aviators, including George Cayley, Octave Chanute, Otto Lilienthal, Samuel P. Langley, Percy Pilcher, and Alberto Santos-Dumont. So we have, unintentionally, saved the most important for last.

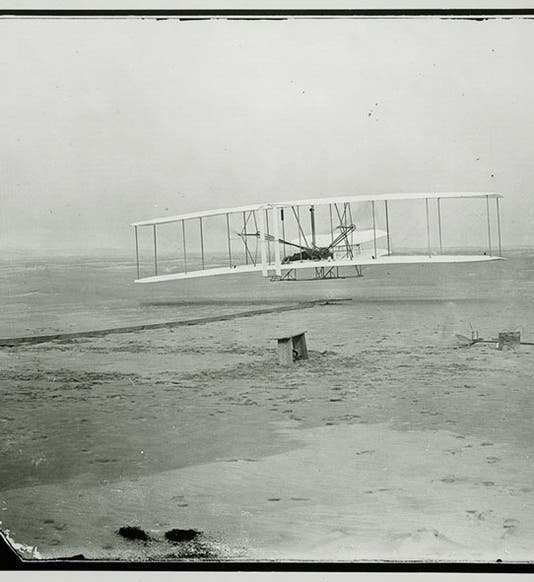

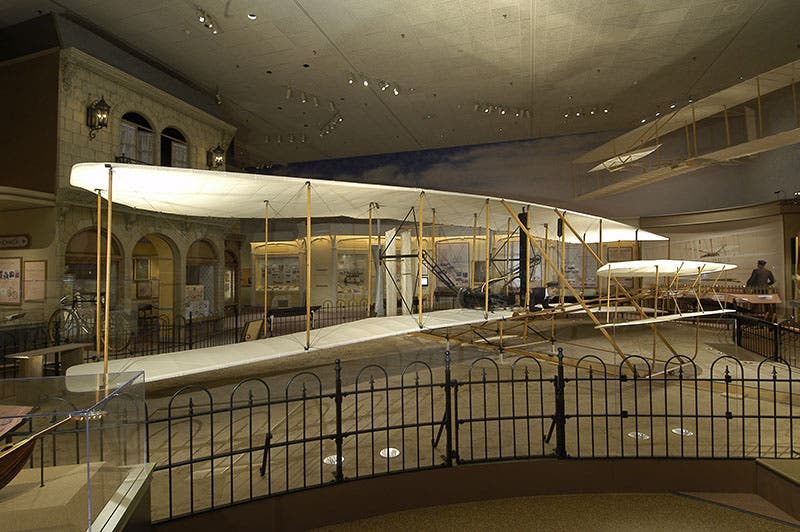

As I think every American knows, Wilbur and Orville built an airplane, now referred to as the Flyer, powered by a small gasoline engine, that they successfully flew four times at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on Dec. 17, 1903. It was the first such flight by a powered aircraft with a human on board. Flyer was the latest in a long line of gliders built and flown by the Wright brothers, but the first with an engine. Flyer had a wingspan of 40 feet and was 21 feet long. There were two wings, one 6 feet above the other, two vertical rudders in the rear (but no real tail), and two horizontal rudders in the front, which we would now call canards. The plane was built of spruce and ash, with the wings covered in cotton muslin fabric, stretched tight. The Flyer weighed 430 pounds without engine or pilot, 605 pounds with engine, and 750 pounds with Wilbur or Orville aboard.

The principal reason the Flyer was successful, and other would-be aircraft were not, is that the Wrights knew how to fly; they had spent over 3 years mastering the art in various gliders. The Flyer was not a notably air-worthy aircraft, especially with the canard wings in front instead of a tail in the rear. But the Wrights learned how to control an inherently unstable aircraft. They were the first to realize that one must be able to control an aircraft on all three axes, roll, yaw, and pitch. They controlled roll by changing the shape of (warping) the wings. Yaw was controlled by the vertical rudders at the back, and pitch by the canards in front. All of these were operated by the pilot lying on the bottom wing. The canards were tilted up or down by a cable attached to a hand lever, and the wings were warped by an ingenious hip-cradle that slid side to side, warping either the right or left wing and causing the craft to roll in that direction, and at the same time deflecting the rudder to control yaw.

It did not hurt that the Wright brothers had a bicycle background. They designed, built, and understood bicycles, and every bicycle rider knows that a bicycle without a rider is the most unstable of conveyances, but that, in motion with a human on the seat, its inherent instability can be completely tamed, once you know how to exert control. So Wlbur and Orville knew that the principal problem to be solved in achieving powered flight was not building an engine, or generating lift – it was controlling the aircraft in flight. And hundreds of hours in their gliders taught them that art.

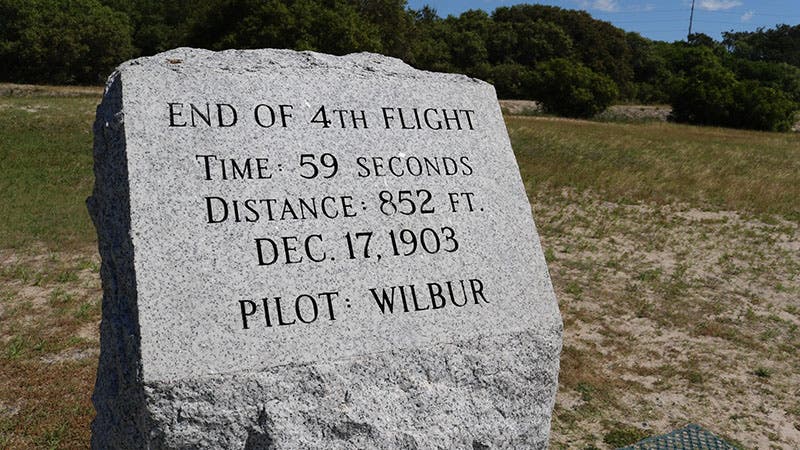

It is hard to separate Wilbur and Orville and their contributions to achieving manned powered flight. Even Wikipedia combines them into one article: “Wright Brothers.” Wilbur is said to have been the calmer, less flappable one, and a little more learned, while Orville had a tad more mechanical ingenuity, but they really were a team. On that momentous day at Kitty Hawk in 1903, they took turns on the wing: Orville was at the controls for the first flight, and Wilbur flew the last one, which resulted in a 59-second flight covering 852 yards, as a marker at Kitty Hawk will remind you, should you visit (third image).

Wilbur was also the one who led the fight against the naysayers and would-be patent breakers, maintaining the originality of the Wright brothers’ design and defending the legitimacy of their patents. Unfortunately, Orville later had to take up this cause, because Wilbur caught typhoid fever and died on this day in 1912, only 45 years old. He did not live to see the Smithsonian Institution deny that the Wright Brothrs were the first to fly, putting forward one of their own, Samuel P. Langley, as the first to build an aircraft capable of human powered flight, and so infuriating Orville that he sent the Flyer off to the Science Museum in London for display. Ultimately, the matter was resolved, the Smithsonian reversed their position and acknowledged the Wright brothers as the inventors of powered flight, and the Flyer was moved to Washington, D.C., where it went on display in 1948. It is now part of a permanent exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.