Scientist of the Day - Washington A. Roebling

Washington Augustus Roebling, an American civil engineer, was born May 26, 1837, in Saxonburg, Pennsylvania. His father, John Augustus Roebling, also an engineer, had come to this country in 1831, to help found a utopian community for other German engineers in Saxonburg, and to improve his prospects for building bridges, which was his passion. John was skilled in making wire rope, which he put forward as the ideal material for building suspension bridges. He established a wire-rope factory in Trenton, New Jersey, and proceeded to build suspension bridges: over the Niagara River just downstream from the Falls, over the Allegheny River in Pittsburg, and over the Ohio River in Cincinnati. Washington, by this time a graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, was intimately involved with the building of the Cincinnati Bridge, and was rapidly acquiring expertise in the making of wire rope and cables.

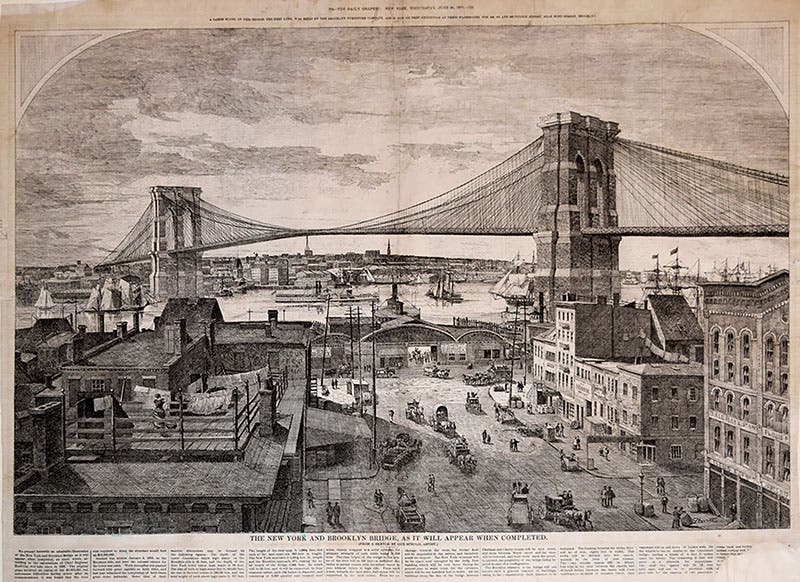

Long before the Cincinnati Bridge was completed (in 1866), John Roebling set his sights on spanning the East River between Brooklyn and New York City. He designed massive Gothic towers that would stand on piers dug down to bedrock, and hold four spun wire-rope cables, which would carry the load of the bridge. He managed to convince both sets of city fathers of the desirability of the project, funding was approved, and work began in 1869. Unfortunately, only months into the project, John had his foot crushed between a ferry and a dock; tetanus set in, and within a month, John was dead. He told authorities before he died that son Washington was perfectly capable of supervising the construction of the bridge, and he was apparently convincing, as Washington was handed the reins. He was 32 years old.

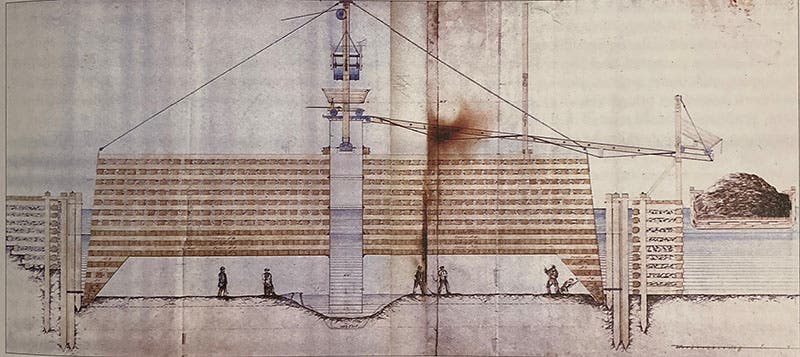

Drawing of the Brooklyn caisson in position, pen and ink, by Washington A. Roebling, 1869, Municipal Archives of New York, reproduced in The Roebling Legacy, by Clifford W. Zink (Princeton Landmark Publications, 2011) (nyc.gov/site/records/historical-records)

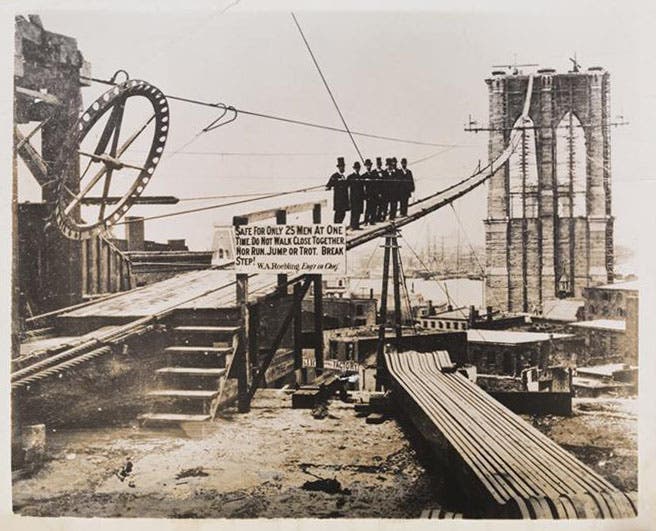

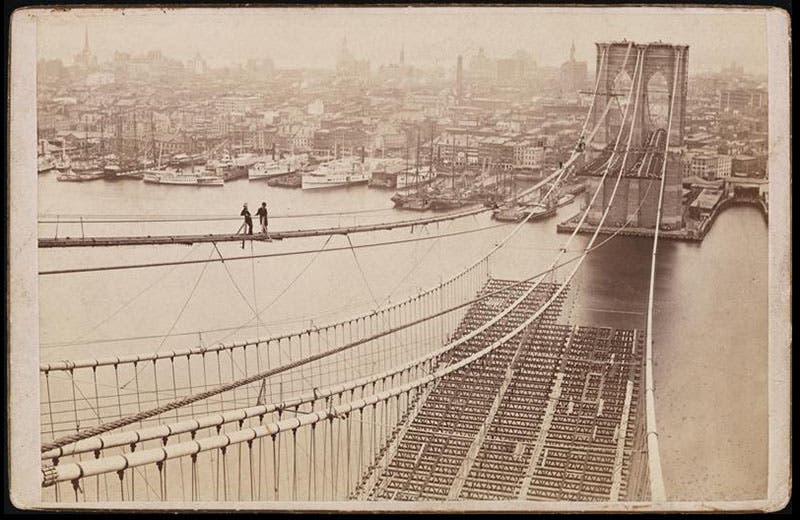

The immediate task was to sink the caissons that would support the 275-foot granite towers on both the Brooklyn and New York City sides of the river (the term “Manhattan” was not in use back then). Caissons were new to the United States; they were simply large (very large) boxes that were placed open-side-down on the river bottom and then pressurized, so that workers inside could dig out the earth or stone beneath and gradually sink the caisson. As the caisson went down, the bridge tower was built up on top, gradually rising out of the water. We show here a drawing of the Brooklyn caisson in Washington's own hand (third image). Charles Eads was using caissons at this very time to build his bridge over the Mississippi River at St. Louis, but no one yet knew about "caisson disease," later to be called "the bends," which began to afflict workers once they were down about 50 feet below water level in the pressurized caissons. One day in 1870, a fire broke out in the ceiling of the Brooklyn caisson, the first to be submerged, and Washington spent several long days down in the caisson fighting the fire. When he emerged, he was struck down with the bends. He partially recovered from this first episode, but another crisis in the New York City caisson took him below again in 1872, and this time he did not recover. He barely survived with his life, and he never returned to the construction site. Afflicted with excruciating pain, sensitivity to sound, and deteriorating eyesight, he worked entirely from home, first in Trenton, then in Brooklyn Heights, for 11 more years, and the only Brooklyn Bridge he would ever see was the one viewed from his window in Brooklyn Heights.

It is astounding that Washington was able to manage so complex an endeavor from a remote location. There were always crises, either with construction or supplies of materials, or with the overseeing board, and somehow, he was able to deal with these by writing letters and memos to his assistant engineers, who were, obviously, very capable. He was also greatly assisted by his wife Emily, who was untrained in engineering or bridge construction, but who learned on the job, as she delivered instructions almost every day and handled problems that required tact and diplomacy, as well as many of a technical nature. The biggest crisis came when the supplier of steel wire for the cables (which was not the Roebling Wire-Rope company, which did not win the bid), was found to have fraudulently substituted reels of defective wire for the wire approved by inspectors, and this defective steel wire was woven into strands and into the cables before the deception was discovered. Instead of starting over, Washington opted to add 150 wires to each of the four suspension cables, bringing the safety factor back up to 5.

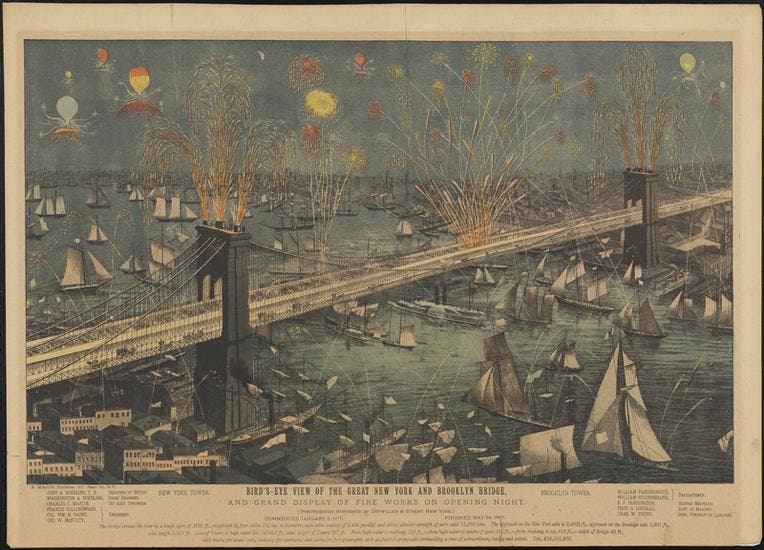

Washington was almost replaced as Chief Engineer, as there was concern that he never showed up on location, and the nature of his illness was kept secret from all but a few. But he had his defenders, and he managed to survive a vote to replace him, thwarting a move led by the new Brooklyn mayor. In the end, the bridge was successfully completed, many years late and way over budget, but still a glorious thing to behold, and it was opened to the public on May 24, 1883, after 14 years of construction. The celebration was long and colorful, as the bridge was at the time the tallest and most massive product of human ingenuity in all of New York City (sixth image). John and Washington were both honored on bronze plaques on the bridge piers, and a plaque for Emily was added later, as the extent of her contributions came to be appreciated.

There are few portraits of Washington; several of him as a young man just out of school, a wedding portrait, and then nothing at all for almost 30 years, which I guess is not surprising – the last thing one with caisson disease would want to do is sit for a portrait artist or a photographer. We showed the formal portrait of Washington, painted in 1899, in our post on Emily, and we include the dual portrait here (second image). We have also written a post on John Roebling, which has some additional information and images related to the Brooklyn Bridge.

During the construction years, Washington many times thought he did not have long to live. But he was wrong. Perhaps having nitrogen bubbles in your blood, however painful, is good for you in the long run, for Washington lived until 1926, when he died at the age of 89.

There is an excellent recent biography of Washington that we have in our collections: Chief Engineer: Washington Roebling, The Man Who Built the Brooklyn Bridge, by Erica Wagner (Bloomsbury, 2017). For those who would like a more succinct but reliable account of Washington's role in building the Brooklyn Bridge, I recommend the chapter on the bridge in Dreams of Iron and Steel, by Deborah Cadbury (Fourth Estate, 2004), which, although it has a few factual errors, does an excellent job of conveying what it was like, trying to build a bridge, while suffering the debilitating pain of caisson disease.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.