Scientist of the Day - Walter Reed

Walter Reed, a U.S. Army physician, was born Sep 13, 1851, in Virginia. He graduated from the University of Virginia Medical School at the age of 17. He spent some time in New York City, getting another medical degree and learning first-hand about public health. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1875, to ensure a stable income for his growing family, and spent 17 years on various tours of duty in the Southwest and Midwest, where several of his brothers lived. He became interested in bacteriology, and on several short tours back in Washington, he took courses in this new field at what would become Johns Hopkins University. He finally returned to Washington for good in 1893, where he joined the staff of the Army Medical Hospital, the George Washington School of Medicine, and took over responsibility for the Army Medical Museum. He became interested in yellow fever in 1896, when he investigated outbreaks of the disease in Washington and discovered that the cases occurred among enlisted men who frequented a swampy area along the Potomac.

Yellow fever was the scourge of the Caribbean, especially among non-natives, who had no acquired immunity. Yellow fever was primarily responsible for the failure of the French Panama Canal effort in the 1880s, as thousands of imported workers succumbed to the disease. In 1898, the United States engaged in the Spanish American War, taking the side of Cuba in its attempts to break free of Spain. The U.S. Army in Cuba, like the Spanish army, was devasted by both malaria and yellow fever, and Reed saw the effects firsthand in 1899. Malaria had just been traced to a parasite, Plasmodium, carried by the Anopheles mosquito, in work done by Ronald Ross in England. Unbeknownst to Reed at the time, a Cuban physician, Carlos Finlay, well before Ross blamed malaria on mosquitos, has suggested in 1881 that a different kind of mosquito, Aedes aegypti, was responsible for transmitting yellow fever. However, Finlay was unable to demonstrate the connection, because he had not discovered that the virus must incubate for over a week in the gut of a mosquito before that mosquito becomes infectious.

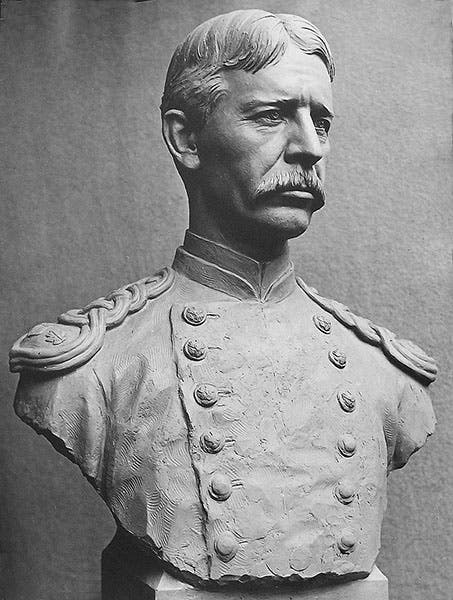

In 1900, the U.S. Surgeon General appointed and sent to Cuba a Yellow Fever Commission to investigate the transmission of the disease (and other tropical diseases). Reed was placed in charge and the other three commission members are shown and identified in the second image. The Commission set up an isolated camp in Cuba in which they could quarantine victims and test subjects. One of the commission members, Jesse Lazear, who had come to Cuba earlier, had met Finlay and learned of his work and the failure of his experiments, and through Lazear, Reed became aware as well. And both knew that Ronald Ross had identified the mosquito as the vector for malaria.

So mosquitos were on the agenda of the Yellow Fever Commission, and they even obtained some Aedes mosquitos from Finlay's laboratory, that they could breed themselves. The problem with yellow fever is that it is caused by a virus, not a parasite, and so it does not show up (like Plasmodium does) in microscopic examination of mosquito guts and red blood cells. But the effects certainly show up, in infected victims, and so that is what they looked for. It was Lazear who made the crucial discovery that it takes 8-12 days for a mosquito to become infectious; if it bites anyone before that, the disease is not transmitted. Finlay had not waited that long to try to re-infect test subjects, and so he was not able to retransmit the disease. It is suspected that Lazear allowed himself to be bitten by a fully infectious mosquito. He came down with yellow fever, and died in September 1900. The epidemiological camp set up by Reed was renamed Camp Lazear. And the transmission cycle was soon a matter of public record. The University of Virginia maintains a website on the Yellow Fever Commission of 1900.

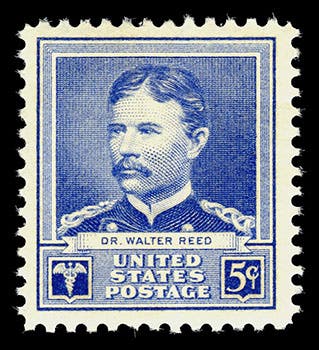

Reed himself was not part of the war on yellow fever that was waged in the Greater Caribbean and in South America over the next 7 years. In fact, I doubt that Reed would be nearly so well remembered and honored as a yellow-fever hero, were it not for the sad fact that soon thereafter, in 1902, he suffered a ruptured appendix and died, age 51. Sometimes you have to die before your time to achieve renown, and have hospitals, schools, and laboratories named for you worldwide (fourth image)

The real hero of the war on yellow fever was William Gorgas, who was sanitation officer in Havana when Reed and the Yellow Fever Commission released their findings. Gorgas was quickly convinced of the truth of the mosquito hypothesis. He concluded that to get rid of yellow fever, you had to get rid of the mosquitos. He got his chance in 1904, when he was appointed chief medical officer of the U.S. Panama Canal Commission. He proceeded to remove all sources of standing water where mosquitos breed, cover cisterns, and screen in sleeping areas, and especially the wards where victims of yellow fever were kept, to keep the mosquitos away. Within 3 years, yellow fever was eradicated in Panama, and the canal project proceeded to its successful conclusion in 1914. We have written a post on Gorgas, and you may also consult the online version of our centennial web exhibit on the building of the Panama Canal, where there is an entire section devoted to the war on yellow fever.

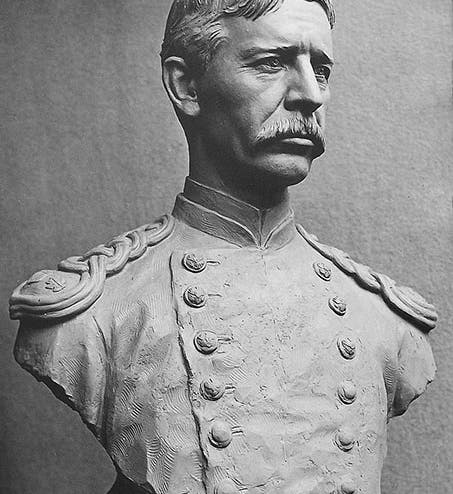

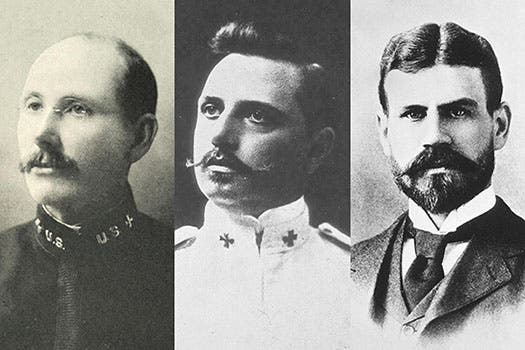

One of the odd minor facts about Reed is that he is almost always portrayed as he looked in 1885, fifteen years before the achievements for which he is remembered. This is true of the portrait bust we showed at the outset, of the U.S. postage stamp (third image), and of the portrait on Wikipedia. So just to expand the record, we include here a photograph taken of Reed in 1901, just after the work of the Yellow Fever Commission was completed (fifth image). One can understand why the effigy of the dashing young officer is preferred.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.