Scientist of the Day - Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh, an English courtier and explorer, died Oct. 29, 1618, losing his head to the executioner's ax; his birth date is not known. However you define a "scientist," Raleigh was not one, but he contributed to scientific knowledge by: a) sponsoring an expedition to settle a colony at Roanoke, North Carolina, in 1585; b) including an artist, John White, on the expedition, thus ensuring a stunning visual record of the Roanoke expedition, and c) being the patron of Thomas Harriot, a brilliant mathematician, astronomer, and cartographer who was in Raleigh's employ for some twenty years, and who, incidentally, wrote A Briefe and True Reporte of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588), describing the Roanoke enterprise.

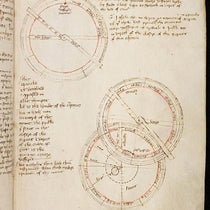

In 1603, Raleigh was convicted of treason, on the flimsiest of charges, and sentenced to death, but King James I stayed his execution indefinitely, and Raleigh was imprisoned in the Tower of London from 1603 to 1616. If you visit the tower, you can see Raleigh’s quarters, or so they claim (second image). He shared the comforts of the Tower with Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland, who had been convicted (also falsely) of participating in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. The Earl had in his employ three "Magi," scientific assistants who reportedly gathered around Percy in the Tower and engaged in alchemical experiments. In many accounts of the "Wizard Earl and his three Magi," Raleigh is often included as an additional member, but there is no evidence of his participation, nor does it appear that the three Magi spent much time in the Tower, preferring Percy’s estate at Syon House. One of the three Magi, interestingly, was Harriot, who for a long while had two masters, but who slowly switched his allegiance from Raleigh to Percy.

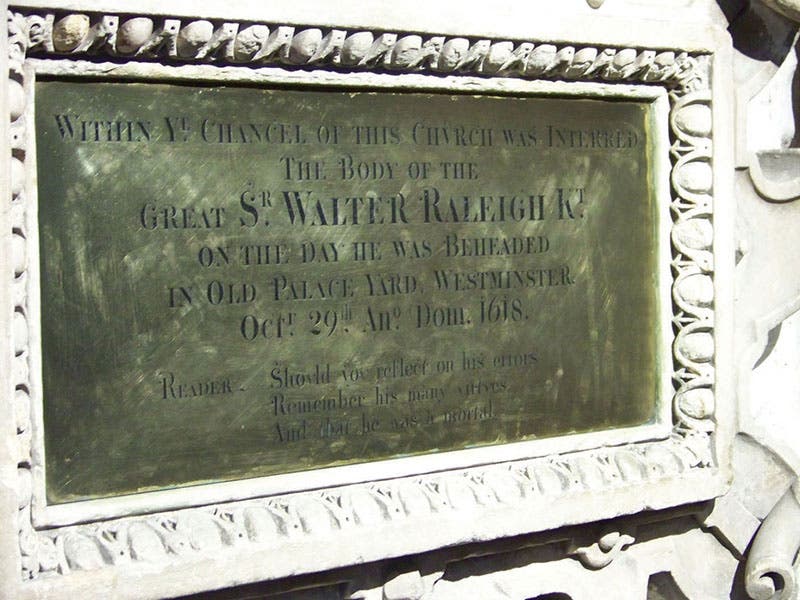

Raleigh was released from prison in 1616 to undertake another expedition, but he plundered a Spanish settlement, which so enraged the Spanish that they complained mightily to James I, who decided to enforce Raleigh’s prior death sentence. Raleigh’s conduct on the gallows was so dignified that his reputation as a great English courtier was reestablished and has remained high ever since. He was executed in the Old Palace yard, Westminster, on the same location where those convicted of the Gunpowder Plot were drawn, hanged, and quartered in 1606 (third image). Raleigh was merely beheaded.

Statue-wise, Raleigh is one of the most honored of Elizabethans; he has a statue in Greenwich (fourth image) and another at his birthplace in East Budleigh (fifth image). The American flag inserted in his hand by an admirer reminds us that Raleigh, North Carolina, was named after Raleigh when the city was founded in 1792.

His only grave memorial is a plaque at St. Margaret’s Church in Westminster (sixth image).

Finally, we note that it is rare for a person who distinguishes himself in adulthood to be the subject of a historical painting as a child, but this is the case with Raleigh, who appears as a young lad just itching to get to the New World in John Millais’s 1870 painting, The Boyhood of Raleigh (last image), which is at the Tate.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.